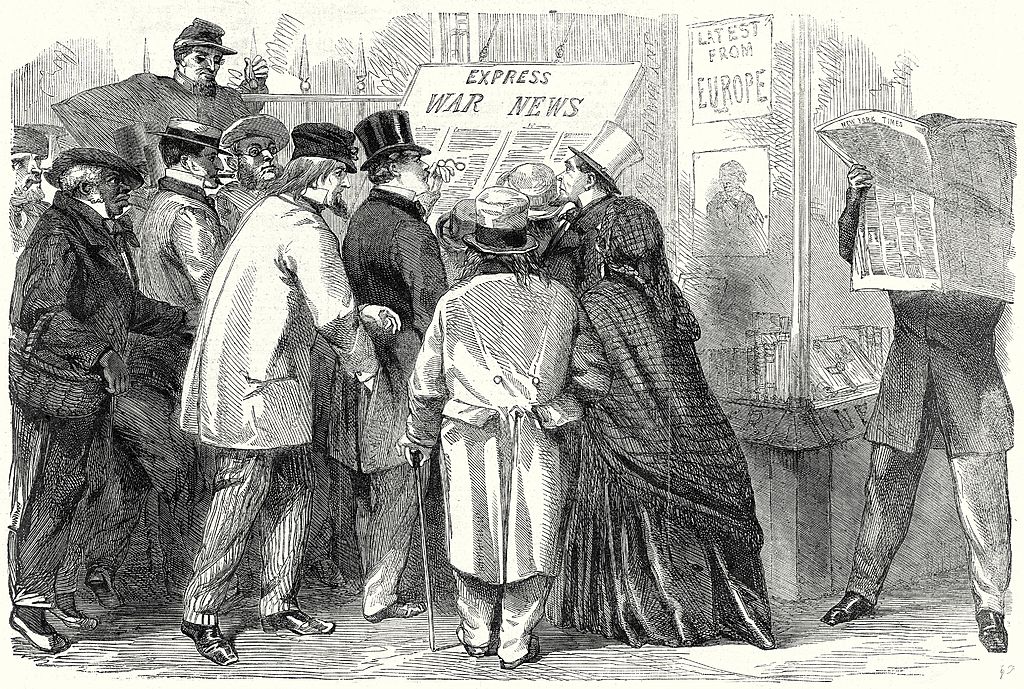

On May 18, 1864, U.S. troops marched into lower Manhattan and entered the offices of two key New York City newspapers. Soldiers leveled guns at staff members’ heads. They blocked the doors with bayonets. President Abraham Lincoln had ordered the arrest of the editors and the seizure of the newspapers. That particular May morning, the papers had run a presidential proclamation announcing a draft of 400,000 new soldiers. The problem: Lincoln had issued no such proclamation.

In the run-up to the 2020 election, American life is full of misinformation about everything from the security of mail-in voting to the causes of West Coast wildfires. Despite efforts to help citizens guard against “fake news,” curtailing misinformation remains a controversial and difficult task. But, while the platforms that help today’s untruths snowball and spread are often decidedly modern, the problem itself is nothing new. During the Civil War, Americans furiously sifted false from true during a time of extreme partisan divisions, even among those who agreed on the need to abolish slavery. They even had their own version of the Internet—the telegraph—which had exposed such stark partisan divisions in the country, its inventor Samuel Morse founded an organization to rebuild national unity. Looking at that time, it’s possible to identify key lessons for navigating this 2020 election season when accusations and false brags about the candidates abound.

We have one key advantage over our predecessors. Civil War-era newspapers rarely listed a reporter’s name on an article. In the 1800s, each newspaper was considered a collective voice and reporters contributed anonymously to that perspective. The lack of personal accountability made it easy for reporters to slip a fake article into the columns. Readers had no idea if the shocking piece had been written by one of their most trusted correspondents or a rascal or even a spy.

Lincoln himself used anonymity to great advantage. His staff members, either anonymously or under pseudonyms, reported on the excellence of his administration as if unbiased. For example, covering Lincoln’s train ride to his inaugural, one correspondent, writing anonymously, noted the crowd’s “frank, hearty display of enthusiasm and affection” for the “tall, stalwart Illinoisan the genuine Son of the West, as perfectly en rapport with its people now… as when he was the simple advocate, the kindly neighbor, the beloved and respected citizen.” The readers would never know that this “anonymous” was actually Lincoln’s press aide.

Correspondence between a Philadelphia newspaper editor and the Secretary of War suggests Lincoln himself likely contributed anonymously to that newspaper while in the White House. “Lest you not see the President’s article in the Press today, I enclose it to you,” the editor wrote. Now, with bylines and Twitter-handle links, we can track authorship and weigh the article against a record of accuracy.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Some things, however, have not changed. For example: It’s important for readers to understand news categories. During the Civil War, newspapers ran a slug over reports from the front: “This is important if true.” Readers understood it to be breaking news from a single source. The information was worth considering but not final. Readers were grateful for glimpses from the frontlines, however hazy, but were reminded to wait for confirmation. Channeling that patience before we rail against or boost a “breaking” story is still valuable.

And if a piece of information makes you cackle, it’s worth rechecking. A recent video posted by Trump’s White House Deputy Chief of Communications appeared to show Joe Biden falling asleep during an interview. The tape spliced a reporter interviewing a relaxing Harry Belafonte with a moment during a virtual town hall meeting when a seated Biden looked down at something. Biden hadn’t fallen asleep in an interview, but the Trump campaign hoped to show him as sleepy. A journalist in 1864 scolded the public for encouraging false stories due to “the popular greed for a large story instead of a true one, the unsatisfied air with which even temperate men throw aside a newspaper which has no striking capitals or startling announcements.”

See if other outlets pick up the story. A New Yorker’s first clue that Lincoln had not authored the proclamation that led to those 1864 arrests was that only two of the 15 or so newspapers clustered around City Hall had included the story in their pages.

And remain skeptical of the President, no matter who that is. He or she is just one source. Although President Lincoln declared the bogus proclamation a complete fabrication, “false and spurious,” which the newspapers had passed “wickedly and traitorously” to the American people, he had in fact written and signed an order for 300,000 new soldiers that very same day. He just hadn’t sent it out. His outrage—and the likely constitutionally illegal act of arresting the editors and stopping the newspapers— covered up what was at its core a leak.

Even “Honest Abe” fudged the truth in this case—proof, if any more were needed, that the problem of misinformation is nothing new. Luckily for those who pay attention to the past, the ways to avoid it are just as enduring.

Elizabeth Mitchell is the author of Lincoln’s Lie: A True Civil War Caper Through Fake News, Wall Street and the White House available now from Counterpoint.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com