In the new film The Glorias, a 1970s-era Gloria Steinem (Alicia Vikander) sits at a press conference with her speaking partner Florynce “Flo” Kennedy (Lorraine Toussaint) where the same journalist asks them separate questions. The reporter asks Gloria about sexual harassment while she asks Flo, a Black lawyer and fervent advocate for women’s rights, about racism. “Do you think Flo is unable to answer a question about the condition of being a woman?” Gloria asks. Flo then explains that racism and sexism are intertwined.

The scene is just one example of the partnerships with women of color Steinem made throughout her life as she became involved in activism and grassroots organizing in the 1960s and ‘70s. It also speaks to what Steinem understood then, as media institutions have only come to understand more recently: how critical it is to ensure that women of color are not sidelined in movements and the way those movements are covered and remembered. The Glorias, which debuted at Sundance in January and is available on Amazon and other VOD platforms beginning Sept. 30, is filmmaker Julie Taymor’s adaptation of Steinem’s 2015 bestselling memoir My Life on the Road. The movie follows Steinem through a series of nonlinear moments foundational to her life and work, from her time traveling in India in her 20s to the rise of Ms. Magazine, as well as the formation of relationships she with other activists who were central to the women’s movement.

As Toni Morrison wrote in a 1971 essay for the New York Times, the intersection between women’s liberation and the movements for civil rights and Black Power was not without its tensions. “What do black women feel about Women’s Lib? Distrust. It is white, therefore suspect,” she wrote. “They don’t want to be used again to help somebody gain power—a power that is carefully kept out of their hands.” And the way in which history has recorded the contributions of activists speaks volumes about who has had the power to shape the narrative for generations to come. But as depicted in another take on the movement from earlier this year, the FX on Hulu series Mrs. America, these disagreements often strengthened the movement, and to overlook them is to do a disservice to history.

The Glorias features several of the leaders who not only shaped Steinem’s activism, but also left a lasting impact on feminism and real-world policies through their work in creating an intersectional movement. Steinem, who is played by four actors including Julianne Moore, shares the screen with Dorothy Pitman Hughes (Janelle Monáe), Dolores Huerta (Monica Sanchez), Flo Kennedy (Toussaint), Wilma Mankiller (Kimberly Guerrero) and a brief tribute to Shirley Chisholm. As might be expected from a biopic focused on Steinem, these women play supporting roles and some have rather limited screen time. (Viola Davis is reportedly producing and starring in a movie about Chisholm, and documentaries have been made about her as well as Huerta and Mankiller, though most of these women await their own proper biopic treatment.) To expand upon their depictions in the film, TIME spoke to historians and feminist scholars about their legacies. Here’s what to know about the contributions they made to the larger movement for equality, their relationships with Steinem and how their activism lives on today.

Dorothy Pitman Hughes

In 1966, a working mother named Dorothy Pitman Hughes could not find childcare in her neighborhood on the West side of Manhattan. So she founded a daycare center herself, charging all families, no matter their incomes, the same rate of $5 a week per child. “For her, it was really important that childcare be available to everyone and not just at the poor end,” Laura L. Lovett, author of the forthcoming and first autobiography on Pitman Hughes With Her Fist Raised: Dorothy Pitman Hughes and the Transformative Power of Black Community Activism, tells TIME. A few years later, that center became the West 80th Street Community Child Day Care Center.

Beyond offering childcare services, the center offered other resources to further support the community, including job training and housing assistance. Through her advocacy and community organizing, Pitman Hughes demonstrated the intersections between childcare and welfare rights—and why they were so vital to the women’s movement. In 1969, Steinem interviewed Pitman Hughes for a piece she was writing for New York Magazine and they soon became speaking partners, traveling the country together for five years.

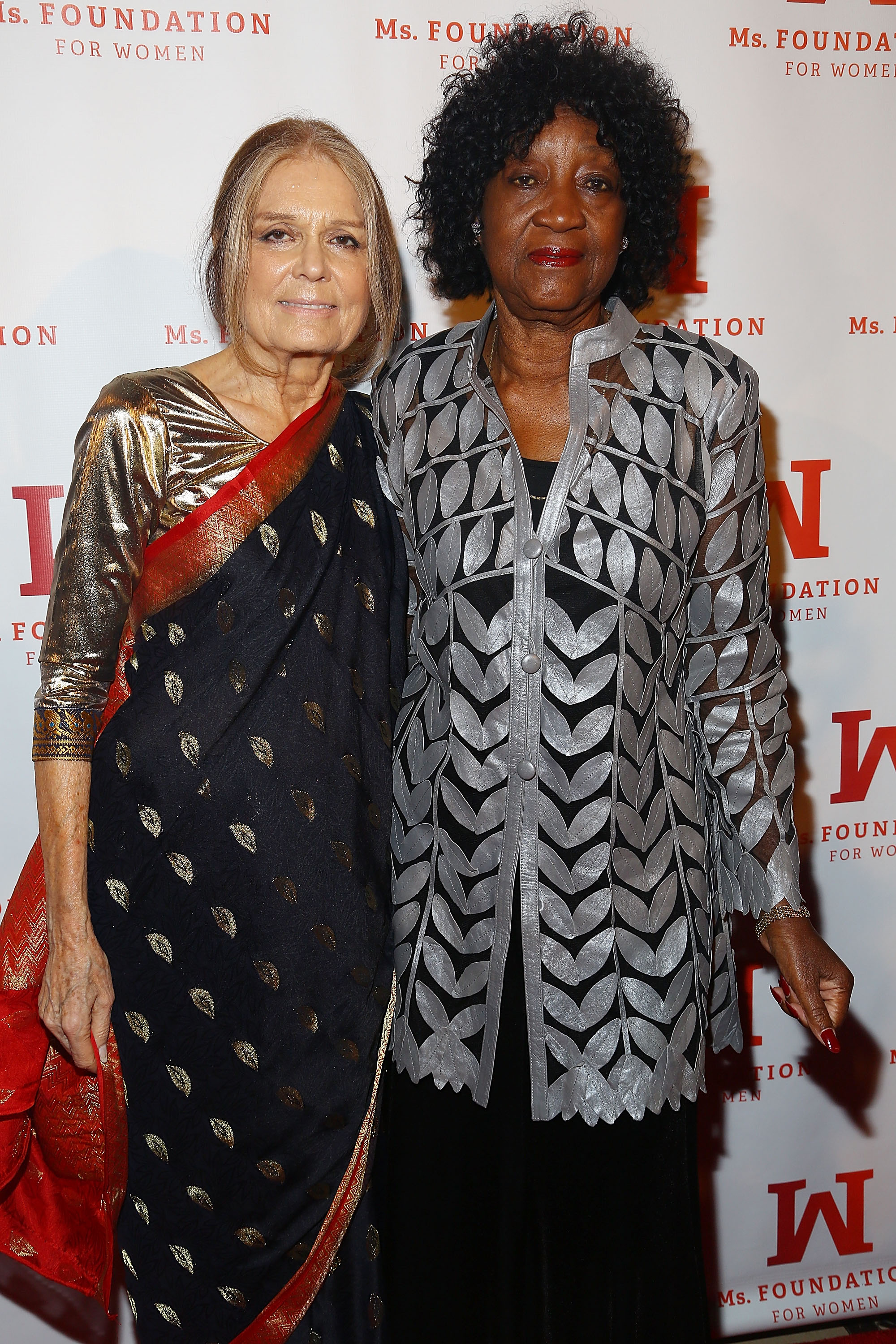

“Gloria was afraid to speak and Dorothy was afraid to fly,” Lovett says. “So Gloria would hold her hand on the plane and Dorothy would hold her hand getting up to the stage. At the time when Gloria begins to talk, Dorothy is the much better known activist.” They were photographed together in 1971 for Esquire Magazine—the now iconic picture shows the two women with their fists raised in the air. It’s that image, Lovett says, that helped push Steinem forward in the mainstream media at the time. While on their speaking tours, Steinem would typically speak first and Pitman Hughes would talk next, according to Lovett. But “the coverage is on Steinem, the press is in love with her,” Lovett says.

Following her time on the speaking circuit, Pitman Hughes, who is now in her early 80s, continued to work as a grassroots organizer on issues important to her community. When she moved to Harlem, she saw the need for a copy center, and decided to open one herself. In doing so, she became an advocate for Black-owned businesses and provided Harlem with a space where political organizers could make fliers. Her work, which was so intimately rooted in community, helped showcase how economic issues like childcare and welfare needed to be at the forefront of the women’s movement.

Dolores Huerta

Since the 1960s, labor leader Dolores Huerta has demonstrated the impact of grassroots organizing on civil rights movements. The activist co-founded the National Farm Workers Association with Cesar Chavez—though the press often minimized her role in comparison to his—in an effort to create better working conditions for farmworkers and illuminate the economic injustices they faced.

In 1965, Huerta played a crucial part in leading a grapeworkers’ strike that became a nationwide boycott. The boycott would lead her to connecting with Steinem in New York City. It was Steinem who got the heir of A&P supermarkets, Huntington Hartford, to protest A&P in support of the farmworkers. The Glorias depicts a moment when Steinem and Huerta, alongside Pitman Hughes, protest together in front of an A&P store. There, Huerta chants “Sí se puede” (Spanish for “Yes, we can”), a slogan she coined and one that later inspired President Obama’s own rallying cry.

While working together, Huerta and Steinem saw how intertwined the workers’ rights and women’s movements were. “For female workers in particular, her role was transformative,” Ai-jen Poo wrote in TIME’s 100 Women of the Year story on Huerta. “At a time when less than 40% of women were in the workforce, Huerta insisted that they have an equal voice at work and in unions, elevated low-wage workers in the women’s movement and mentored young female activists across the country.”

In 2011, President Obama awarded Huerta with a Medal of Freedom. Now 90, she continues to be an active part of the labor movement through her work at the Dolores Huerta Foundation, which organizes communities and empowers leaders within them to fight for social justice. In June, amid the protests occurring around the country in the wake of George Floyd’s killing, Huerta talked to TIME about how to sustain a movement and described how she encouraged her grandchildren to protest. “I mean this is like a punishment for me not to be out there,” Huerta said. “I just wanna bless and thank all of the protesters.”

Florynce “Flo” Kennedy

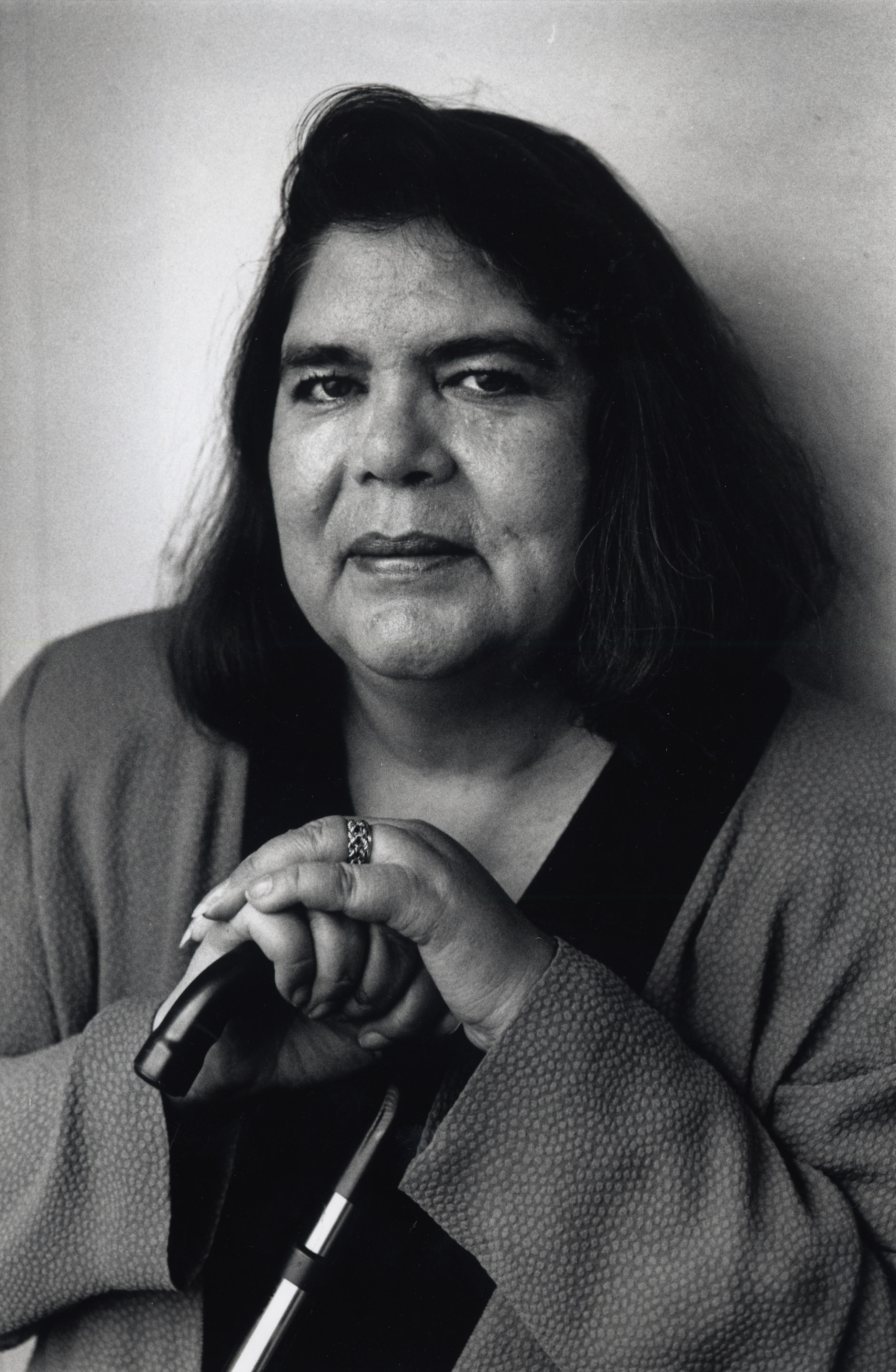

Lawyer and activist Florynce “Flo” Kennedy made essential connections between the Black Power and feminist movements. After becoming one of the first Black women to graduate from Columbia Law School, in 1951, Kennedy opened her own law firm. In the years that followed, she went on to represent Billie Holiday, H. Rap Brown and a group of Black Panthers. By 1966, she created the Media Workshop, which fought racism in advertising.

Kennedy eventually pivoted towards political activism and became a staunch advocate for civil rights issues. In 1969, she began efforts to challenge New York state’s abortion law, which led to the state liberalizing abortion the following year. Kennedy incorporated into her work a deep understanding of how racism impacts every facet of society—a founding principle that she brought with her to the women’s movement. In 1971, Kennedy founded the Feminist Party, which went on to nominate Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm for president.

Sherie Randolph, an associate professor of history at the Georgia Institute of Technology and author of Florynce “Flo” Kennedy: The Life of a Black Feminist Radical, spoke to TIME about Kennedy’s central role in the women’s movement during the 1970s. “In Flo’s mind, there was a Black Power movement that Black people should be involved in and that should be intersectional,” Randolph says. “The women’s movement needed to do a better job of being anti-racist and Gloria Steinem had an ear for that.”

Kennedy, who was almost 20 years Steinem’s senior, became her speaking partner. An energetic speaker known for her humor and cowboy hats, Kennedy spoke about racism and sexism to audiences across the country. Randolph says that Kennedy’s mentorship of Steinem during this time illuminated how necessary it was for the women’s movement to be intersectional. Kennedy brought white feminists to Black power conferences, and, according to Randolph, introduced Steinem to people within her circles who helped broaden her perspective on a range of intersectional issues.

Though she was at the center of the women’s movement, Kennedy hasn’t been as widely recognized for her work. “Thankfully, we’re now living in a different moment where you have to acknowledge Black women a little bit more and their influence on predominantly white feminism,” Randolph says. “They weren’t just an antagonistic force—they were a force propelling questions as well. And that’s what Flo helps to emanate.”

Wilma Mankiller

When she was a child, Wilma Mankiller and her family were relocated from Oklahoma to San Francisco as part of the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Relocation Program. It was there that Mankiller, who faced the twin challenges of discrimination and poverty, became involved in the civil rights and women’s movements of the 1960s. She returned to Oklahoma in 1977, carrying with her what she learned from that time to fight for indigenous rights and gender equality.

In 1985, she became the first woman elected Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation. In The Glorias, Mankiller gives a speech on the day of her election. “We, Cherokee, consult our women elders on every important decision, but we’ve never had a woman as a democratically elected chief,” she exclaims. Mankiller and Steinem met when Mankiller joined the board of Steinem’s nonprofit, the Ms. Foundation for Women. They became political allies and formed a deep and long-lasting friendship. “Her success in achieving economic autonomy for her people made her a symbol of hope for original cultures and women’s movements around the world,” Steinem wrote for TIME in 2010.

In the early 1980s, before she pursued elected office within the Cherokee Nation, Mankiller proved her skills as a leader and organizer during the Bell Water Project, helping to bring a reliable water delivery system to the small Oklahoma town populated largely by Cherokee citizens. “She was integral to the project and it brought her to broader attention in terms of Cherokee Nation politics because people saw that she is someone who gets things done,” Candessa Tehee, an assistant professor of American Indian studies of Northeastern State University, tells TIME. “She has such a rich legacy, especially in terms of her continued effort for guaranteeing tribal sovereignty, the fight for indigenous rights, feminism and education.”

Tehee says that Mankiller was constantly reaching out to individual Cherokee women to try to inspire more political activism and engagement within the community. As Principal Chief, she laid the groundwork for self-governance, economic success and new policies on healthcare and education. Steinem was one of the featured speakers at Mankiller’s memorial service after her death in 2010. “In a just country, she (Wilma) would have been president,” Steinem told the Oklahoman.

Shirley Chisholm

While there’s not a character specifically depicting Shirley Chisholm in The Glorias, there is a character with a small role named Shirley, included by the filmmakers as an homage to the politician. But Chisholm’s involvement in the movement as an activist, politician and grassroots organizer is so significant that it bears inclusion here.

In 1968, Chisholm became the first Black woman elected to the United States Congress. Four years later, she became the first Black woman of a major party to run for the presidential nomination. “Shirley Chisholm never saw her achievement as being a ‘first,’” Zinga A. Fraser, assistant professor and director of the Shirley Chisholm Project on Brooklyn Women’s Activism at Brooklyn College, tells TIME. “She saw it, in many ways, as the way to create more opportunities for women of color and Black women, specifically, to elected office.”

As a congresswoman, Chisholm was never the type of politician to sacrifice her ideals in order to advance politically. “Her true political genius is the importance of being what she would consider to be ‘unbought and unbossed’ and really not confining herself to engaging in politics that were amenable just for compromise,” Fraser says. She sees Chisholm’s bold tactics in the new guard of congressional women of color, sometimes called the “Squad,” who, despite their freshmen status and lack of capital, go head-to-head with established politicians. Fraser adds: “When Chisholm emerges during that time period, she creates an atmosphere specifically for young, marginalized people to align themselves against institutions and structures of power.”

In 1971, Chisholm founded the National Women’s Political Caucus alongside Steinem, Dorothy Height, Bella Abzug and others. In reflecting on Chisholm’s influence on people like Steinem, Fraser says that it was through her analysis of policies and her ability to highlight the everyday issues that impacted women. “Chisholm had a larger understanding of what intersectionality was even before the term was coined,” Fraser says. “She had a nuanced perspective about politics and about ways in which feminism has to speak to a multi-racial and multi-generational coalition.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Annabel Gutterman at annabel.gutterman@time.com