Ellen Urbani shook her head in disbelief as she scanned the cobwebbed shelves of her suburban garage, looking for items that might protect her at a Black Lives Matter protest. “This is absurd,” she thought. “I can’t believe I let people talk me into thinking I need this stuff.”

She dusted off her son’s snowboard helmet and hooked it onto a backpack that held her daughter’s swim goggles, her asthma respirator and a change of clothes in case the long-sleeved yellow V-neck she was wearing burned off from chemical gas. She scribbled her husband’s name and phone number on her thigh in permanent marker, in the event she became incapacitated. With her auburn hair braided into pigtails, the 51-year-old author then left the safety of her 43-acre farm outside Portland, Ore., on July 24 to link arms with hundreds of other mothers demanding justice for George Floyd.

By midnight, Urbani says, federal agents had enveloped the protesters in a cloud of gas, and flash grenades exploded. Projectiles as big as softballs began to fly. As the women around her choked and vomited from the fumes and as bodies began crashing into each other, Urbani reminded herself that she’s “just a mom,” a law-abiding former Peace Corps volunteer and a threat to no one. “Then I felt my bone break,” says Urbani. “It felt like being hit by a 90-m.p.h. baseball.”

While taking part in the largest sustained social justice mobilization in modern U.S. history, dozens of people have been beaten with batons, hit by cars, doused in pepper spray and critically wounded by rubber bullets, beanbag rounds and other police weapons. More than 93% of Black Lives Matter protests across the U.S. have been peaceful, according to an analysis of more than 7,750 demonstrations from May 26 to Aug. 22 by the nonprofit Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project. Even so, at least 115 protesters were shot in the head, face and neck with various projectiles, including bullets and tear gas canisters, from May 26 to July 27, according to a report by Physicians for Human Rights. The nonprofit health-advocacy group compiled its data from news and medical reports, social media posts and lawsuits.

Compared with other Black Lives Matter protesters injured by law enforcement, Urbani knows she is one of the luckier ones. She was hit in the foot by what she believes was a rubber bullet, which shattered her big toe. It’s slowly healing as she undergoes physical therapy, but her mental anguish is here to stay. “I never thought I’d be shot in my own city by my own countrymen,” says Urbani, who comes from a military family and who had always respected law enforcement.

I never thought I'd be shot in my own city, by my own countrymen.

In the competition to define what has happened in America’s streets since Floyd’s death on May 25, critics of the protests point to the handful of cities where stores were burned or looted. Advocates for protesters reply that, regrettable as those incidents may be, property can be restored. But the bodies of demonstrators have been irreparably damaged—often in incidents documented by cell-phone cameras, posted to social media and replayed on local and national news. Millions of people saw footage of a young woman being knocked to the ground in New York City and of an elderly man bleeding from his ear after being shoved to the pavement in Buffalo, N.Y. They watched as a New York Police Department (NYPD) vehicle sped up and drove into a crowd of protesters.

In each case, the outrage is compounded by the setting: a protest over police brutality. And months later, after the attention has shifted elsewhere, the injured are left to navigate a new set of challenges: mounting medical bills, job losses, unquenchable anger and time-consuming lawsuits that end up costing taxpayers more than they cost the targeted police department. Only occasionally do they see the officers who have changed their lives charged with crimes or fired from their jobs.

“It’s not the police departments that feel the weight and burden of it,” says Jennvine Wong, a staff attorney with the Legal Aid Society.

In New York City alone, taxpayers spent $220 million to settle more than 5,800 lawsuits filed against the NYPD during the 2019 fiscal year, according to the latest data released by the city comptroller. In 2018, Chicago taxpayers spent more than $113 million—the highest amount since at least 2011—to settle police-misconduct lawsuits and pay for outside lawyers, according to an analysis by the Chicago Reader. Breonna Taylor’s family settled with the city of Louisville, Ky., for $12 million after police shot her to death in her own apartment, but protests have continued over the decision not to prosecute officers for her killing.

“My faith in this world is gone,” says Dounya Zayer, the young woman who was pushed by a police officer during a Black Lives Matter march in New York City on May 29. The 21-year-old had a seizure after her head smacked against the curb and has yet to recover from the concussion and back injury that she suffered. “I’m angry and scared and depressed,” she says. “I know I’m not the only one.”

***

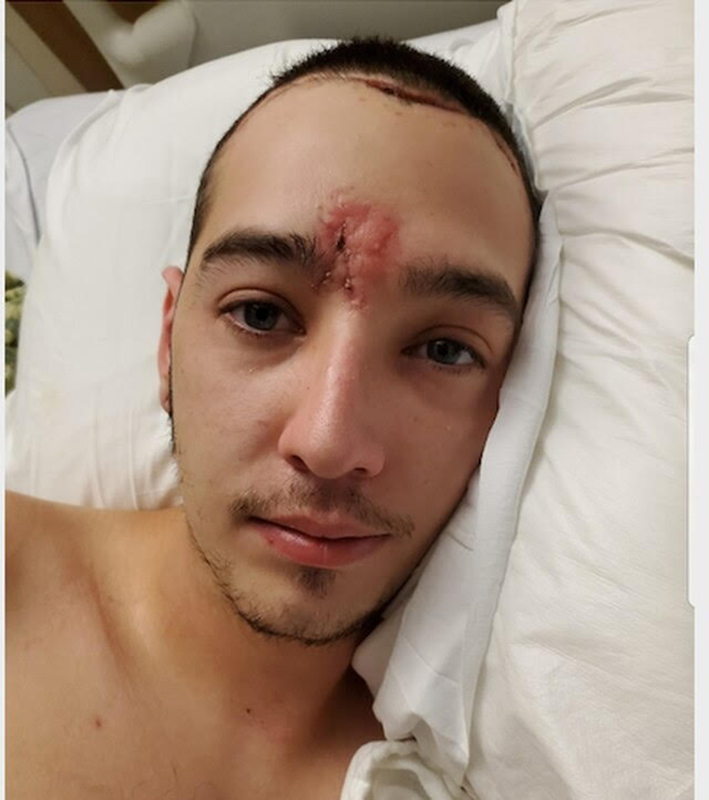

On July 11, Donavan La Bella was holding a stereo above his head at a Portland, Ore. protest, blasting a song by the artist Dax called “Black Lives Matter,” when a line of U.S. Marshals across the street began launching smoke canisters. Cell-phone footage shows La Bella, 26, calmly kicking aside a canister that landed at his feet, then picking it up and tossing it away before lifting the stereo above his head again. Seconds later, as La Bella stands in place, not moving toward the officers, he’s shot between the eyes with an “impact munition” and drops to the ground.

La Bella’s skull was fractured, and the bones around his left eye socket were broken. He has trouble concentrating and controlling his emotions and suffers from extreme sensitivity to light and sound and impaired vision, says his mother, Desiree La Bella. “Try to imagine having a migraine for a minimum of 12 hours a day for five, six weeks straight,” his mother says. “You can’t get away from that kind of pain.” La Bella spent most of the past two months in the hospital, having returned there on Aug. 17 for the third time to treat a sinus and brain infection as well as a cerebrospinal fluid leak, conditions related to his injuries.

“The trauma we are facing now is long-lasting,” says Zayer, who still has seizures, suffers migraines and struggles to keep food down. The former competitive gymnast is in physical therapy up to five times a week when she’s not sitting in a waiting room to see multiple specialists. “Physically and mentally, I feel like a whole different person,” she says. “I don’t think I’m ever going to be the same.”

Zayer was one of dozens of protesters who testified in June about being shoved, kicked and violently wrangled by police, during a three-day public hearing held online by the New York attorney general. Some displayed cuts and bruises as they told investigators they were kicked in the jaw, thrown against brick walls and pushed off bikes. NYPD Commissioner Dermot Shea testified that hundreds of police officers were injured during the first few nights of protests as some demonstrators looted and threw bottles, bricks, trash cans and rocks at them. Others set fire to police vehicles and attacked precincts. “This was some of the worst rioting that occurred in our city in recent memory,” he said, adding that it’s difficult for officers to avoid interacting with peaceful protesters while dealing with violent ones. Since protests erupted in the city on May 28, an NYPD spokesperson said, more than 470 officers have been wounded, including 20 who have not yet recovered enough to return to work. Zayer and other witnesses challenged that narrative.

“I didn’t often see cases where protesters were fighting back,” said Whitney Hu, a Brooklyn activist who aided Zayer and more than a dozen others who were pepper sprayed or beaten with batons. “I saw protesters hiding or trying to help others who’ve been wounded.”

***

Shantania Love, a 30-year-old Sacramento mother of two, was walking away from law enforcement officers at a protest in Oak Park, Calif., around midnight on May 29 when they started firing projectiles to disperse the crowd. Love believes a rubber bullet hit her in the eye, permanently blinding her in that eye, as she turned around to look for her brother. “My eye was blown to pieces,” says Love, who underwent two surgeries in an attempt to save her vision. “It was probably the worst pain I’ve ever felt, and I pushed out two kids.”

Love now struggles with mundane tasks like pouring a cup of juice or walking up and down the stairs because of her skewed depth perception. For days, her youngest daughter, who is 5, cried when she saw Love’s wounded eye. Love hasn’t been able to return to work as a medical assistant and consequently lost her health benefits in August. “I have to pay for everything myself,” she says through tears.

“Her life has been so radically altered, it’s just devastating,” says Love’s lawyer, Lisa Bloom, who filed a lawsuit against the city and county of Sacramento, the state of California and numerous officers for damages. “It may have been a split second for them to pull the trigger. It’s a lifetime of pain for her and many others.” A Sacramento Police Department spokesperson said the department has not yet confirmed it was responsible for Love’s injury, since multiple outside agencies responded to the protests. The incident is still under review.

Many of the weapons used by police in recent protests, like rubber bullets and beanbag rounds, are deemed “less-lethal” by law enforcement, even though they can maim and kill. From January 1990 to June 2017, at least 53 people died after such weapons were used for crowd control in incidents around the world, according to a 2017 study published in the medical journal BMJ Open. Three hundred others suffered permanent disability, often from being struck in the head and neck. “Bullets by another name are still bullets,” says Dr. Rohini Haar, the study’s lead author. As an emergency doctor in Oakland, Calif., Haar says she witnessed the damage of the projectiles firsthand in 2014, when rubber bullets were used on Black Lives Matter protesters amid unrest over a St. Louis grand jury’s decision not to charge the officer involved in Michael Brown’s shooting death. When police answered protests with violence in 2020, she was not surprised.

The level of violence that police officers have used throughout history, against people exercising their constitutional right to protest, is really quite staggering.

Neither were historians. Recent accounts of police aggression mirror those seen multiple times in American history, according to historian and author Heather Ann Thompson, who studies 1960s and ’70s policing and protest movements. Her book, Blood in the Water, about the Attica, N.Y., prison uprising, won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize in History. “There’s a long, long history of this,” says Thompson, citing the 1968 protest at the Democratic National Convention and a massacre that same year in Orangeburg, S.C., in which law enforcement killed three students and wounded more than two dozen others during a civil rights protest. “The level of violence that police officers have used throughout history, against people exercising their constitutional right to protest, is really quite staggering,” she says.

What’s new, Thompson says, is that police are militarized, often with surplus U.S. Army equipment designed for use in wars of occupation. And in 2020, police actions, and those of white, far-right groups claiming to want to protect businesses and towns from protesters, have been emboldened by a sitting U.S. President, she says. “None of these other presidents would have verbally celebrated white-vigilante, racist violence the way that Donald Trump has,” Thompson says.

Trump has generalized Black Lives Matter protesters as “violent anarchists” and threatened to quell demonstrations with federal forces. “These are not ‘peaceful protesters,’” he tweeted in part on Sept. 8. “They are THUGS.”

***

During the decade that Martin Gugino has spent protesting, the 75-year-old retiree has been arrested at demonstrations four times and faced charges ranging from misdemeanor trespassing to demonstrating without a permit. He had never been convicted in court or injured at a protest until June 4, when a police officer in Buffalo, N.Y., pushed Gugino onto the pavement. In some of the most graphic footage to emerge from the protest movement, Gugino is seen staggering backward, then falling on his back to the sidewalk, his head slamming to the ground. Blood leaks from his ear, and more than a dozen officers in riot gear stream past the apparently unconscious man without helping him.

The last thing Gugino remembers seeing is a line of helmeted officers coming toward him with batons. “When I was in the hospital,” Gugino says, “I thought, ‘What’s all the fuss about?’ And then I saw the video and I said, ‘Oh yeah, I get it.’” He suffered a fractured skull and concussion and was hospitalized for about a month—the last three weeks of which were spent in physical therapy, relearning how to walk. When he was first hospitalized, Gugino says he could not hear anything because his ears were full of blood. Gugino, who’s hoping for a full recovery, says the experience was a small sample of what Black people endure on a daily basis. “It’s unacceptable,” he says of police violence. “They need to be corrected. The cops have just got the wrong idea. And bad ideas have bad consequences.”

Some officers are facing those consequences. On June 6, prosecutors charged two officers involved in Gugino’s incident with felony assault. Four other law enforcement officers in Indiana and Philadelphia are facing assault charges for clashes caught on camera. One is accused of pepper spraying protesters in the face while they were kneeling. Another allegedly clubbed a college student on the head with a metal police baton, resulting in a gash that required about 20 staples and sutures, according to prosecutors.

The New York City police officer who pushed Zayer, Vincent D’Andraia, was charged with misdemeanor assault and faces up to one year in jail if convicted. D’Andraia was initially suspended from the force for 30 days without pay. He’s now on modified assignment while he awaits a court hearing, an NYPD spokesperson said. His lawyer declined to comment. “They put a Band-Aid on a bullet wound,” says Zayer, who wanted D’Andraia to be fired.

For people whose cases don’t end in charges against police—often because their injuries are not caught on camera—the only way to seek accountability is through civil lawsuits. On Aug. 24, Urbani and three other injured demonstrators filed a class-action lawsuit, claiming the federal agents Trump deployed to Portland used “unconstitutional and unnecessary force” against protesters. Attorney General William Barr defended the agents’ actions in testimony before the House Judiciary Committee on July 28, saying “violent rioters and anarchists have hijacked legitimate protests.”

Even when departments settle lawsuits, they’re rarely required to admit fault, meaning the injured may walk away with some funds to help pay medical expenses but no acknowledgment of wrongdoing. Love knows that, and that no amount of money will replace her eye. But she would rather fight for a piece of justice than do nothing.

“I have children,” she says. “I don’t want them to grow up in a world where this type of behavior is tolerated.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com