In the fall of 2016, I had an informal meeting with a group of political leaders from Eastern Europe and asked them how they defended themselves against constant Russian efforts to meddle in their elections. Their answer surprised me but made perfect sense. The best defense, they said, is for the people to know it’s happening, so they can just shrug it off; “The hell with it; it’s just the Russians again!” Similarly, when the Russians tried to interfere with the national elections in France in 2017, the French government publicized what was going on and the project fizzled.

Unfortunately, this is not the case here. Although our intelligence agencies keep track of what foreign governments (including the Russians) activities are underway to interfere with our elections, they rarely, if ever, share what they know publicly. This robs our citizens of critical information they need—like the source of the latest conspiracy theory—to weigh the flood of information (and misinformation) coming at them.

Why do we spend billions of dollars each year collecting intelligence from all over the world, analyzing and sifting it, and preparing detailed reports of what our adversaries are up to? The answer is easy—to provide policy-makers with good information upon which to make important, often life or death, decisions. And who are those policy-makers who are privy to this information, who “need to know”? Generally, it’s a short list; the president, first and foremost, followed by the national security apparatus, certain cabinet members, and, sometimes, a select group in the Congress.

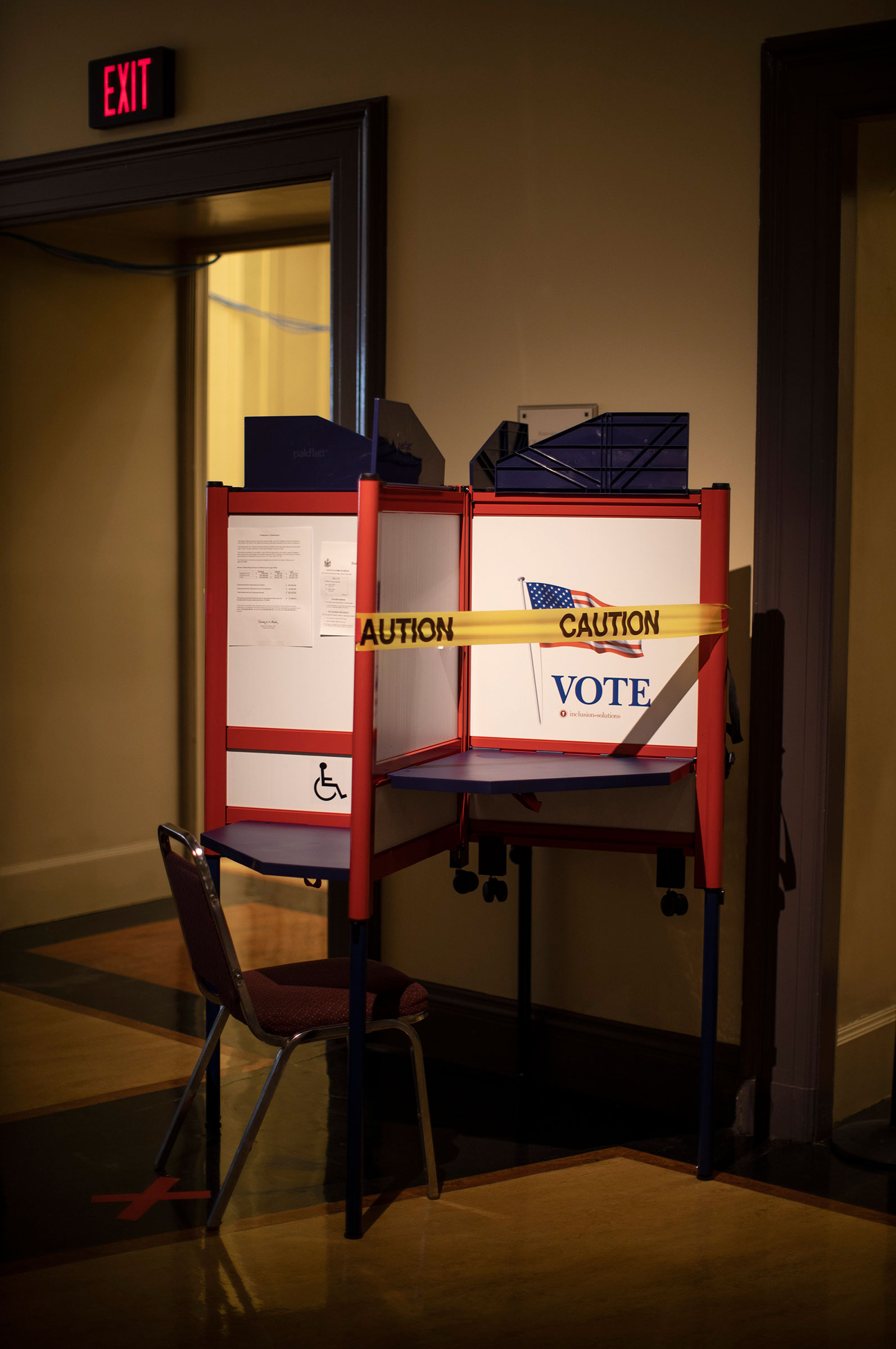

But there are important occasions where the decision makers are not any of those officials I listed. They are instead the American people. Those occasions are called elections—and before making their critical choices, the people should be entitled to that portion of available intelligence that would be helpful in informing their decision. Information is the coin of the realm in a democracy, and it should not be hoarded by a select few.

Our Constitution starts with the words “We the People” for a reason. Power in our system does not come from the states, from corporations, from inheritance, from divine decree, or from those already in office; it comes from the people themselves, and that power is expressed most directly in regular elections. As they say, this is not a bug in our system, it is a feature. So why shouldn’t the people have the benefit of information collected on their behalf (and using their tax dollars) when exercising this crucial decision-making power?

Here’s a concrete example. In every democratic system from time immemorial voters have been flooded with negative charges and countercharges, misinformation, and often downright slanderous accusations. This is nothing new. What is new in recent years is the extensive use of these tactics by foreign governments to further their own ends in our elections, whether to sow chaos and dissension, or to assist a candidate they believe will be more amenable to their interests.

In a free society, it’s awfully hard to guard against this; we can’t pull the plug on our TV’s or block the internet (which, by the way, is exactly what happens in some of the countries with which we are contending these days). We have the First Amendment and the tradition of unfettered communication, whether in an old-fashioned newspaper, a cable network, or the wild west of YouTube, Facebook, blogs, and podcasts. But there is one defense, as mentioned above—and that is for the people to know when a foreign government is the source of the latest conspiracy theory or sensational charge—and that’s where intelligence comes in.

My thesis is simple: if the intelligence community knows when and how this is happening—that foreign powers are trying to undermine an election, whether through interference with the election process itself, hacking one or both of the campaigns, or creating and spreading disinformation, they should immediately tell the American people. How they got this information (“sources and methods”) can be protected, but that should not be used as an excuse to keep the people in the dark when the future of the country is at stake.

Unlike those Eastern European countries I mentioned earlier, Americans aren’t yet conditioned to be sufficiently skeptical of what we see floating through our Twitter scrolling or Facebook meandering. We, too, need to heighten our media literacy by instilling in our citizens some basic methods of verifying information – and this begins with a well-sourced government alert. If the National Weather Service issues a hurricane warning, Americans hunker down; if we receive an Amber Alert on our phones, we grow more vigilant. In much the same way, a “Foreign Source” push announcement or a flag of some form on a social media platform could deflate a myth before it gains traction – and protect our elections.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com