One: Get police departments across the country to report when their officers use lethal force or seriously injure someone. Two: Collect that data in a national database. Three: Release those statistics to the public on a regular basis.

That simple formula has been at the heart of every single police reform proposal in modern U.S. history. Police chiefs, community members, Republicans, Democrats, federal, and local lawmakers all agree that the absence of a comprehensive collection of use-of-force incidents by the nation’s police is a roadblock to reform. But despite longstanding bipartisan agreement on the need to keep those national statistics, a 26-year-old federal law mandating that the U.S. government collect this information, and a five-year effort by the FBI to put the infrastructure for a database in place, Americans in 2020 still have little to no reliable data on their police departments’ use of force across the country.

“I’ve been around so long and it seems they just keep rediscovering the wheel,” said Geoffrey Alpert, an expert on police use-of-force and criminology professor at the University of South Carolina. When he testified on President Donald Trump’s Presidential Commission on Law Enforcement at the Justice Department on June 19, it covered “the same thing I’ve talked about for 30 years” in similar meetings during the Bush, Clinton and Obama Administrations, he said. If Americans want better police accountability, the government needs to find a way to get police departments to document and report their use of force to a national database, and provide them the resources to do so. “It’s always been obvious: if we don’t know the data, how do we identify the problem?” Alpert asked. “The only way forward is with evidence, but we continue to spin in circles.”

As of May, only 40% of police departments across the country had submitted information to the FBI’s National Use-Of-Force Data Collection, the most recent effort to collect this data, an agency spokeswoman told TIME. The FBI database, which began collecting the information in January 2019, has run into the same fundamental issue that has stalled decades of previous attempts: there is no way to compel police departments to provide this data to the government. Any federal data collections like the FBI’s rely on voluntary participation, giving both an incomplete and skewed picture of how police officers are using force across the country. “The only agencies willing to report this were those feeling good about their data,” says Alpert.

Truly “mandatory” federal data reporting would require an act of Congress. In other words, lawmakers would have to pass legislation requiring state and local police departments to provide the information. Legal experts tell TIME that it’s not clear Congress would even have the power to pass such a law; whether or not the government can compel states to share their use-of-force data would depend on whether it is deemed to run afoul of the anti-commandeering doctrine, a legal principle that says the federal government can’t force states to carry out federal programs.

Partly because of this division of responsibility between the federal government and states laid out in the 10th Amendment, which means Congress has little power over state and local law enforcement, there are few examples of mandated data collection by the federal government. Experts point to the decennial Census, which requires people to provide their information to the government, or the 2003 Prison Rape Elimination Act, which mandates correctional facilities to provide data on prison sexual assault.

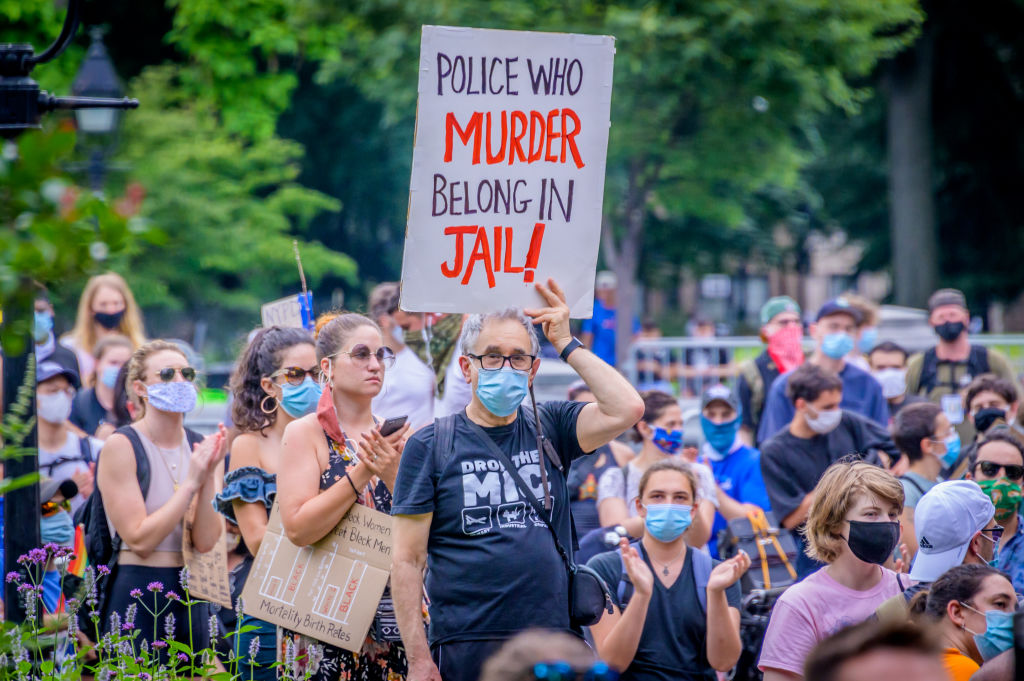

The nationwide protests after George Floyd’s killing in May by a Minneapolis police officer with a previous record of excessive force have revived efforts to collect better use-of-force data. Trump’s June 16 executive order, as well as the competing police reform bills put forward by House Democrats and Senate Republicans, all seek to create a more complete database by tying federal grant funding to agencies that regularly report this information up the chain.

But police chiefs, former FBI and DOJ statisticians, and law enforcement analysts tell TIME that the current momentum is likely to hit the same roadblocks it’s been hitting for decades —unless lawmakers focus more on what has stalled previous failed efforts and less on toothless mandates that look good on paper.

The carrot approach of offering grants to agencies might work to some extent, some experts say. “Almost everyone is getting federal funding of some type, and they certainly don’t want to risk that, so it can be an effective tool,” says Matthew Hickman, chair of the criminal justice department at Seattle University and a former Bureau of Justice Statistics analyst. A successful example of that approach is the way that Washington leveraged federal highway funding to get states to comply with driving-related laws such as establishing speed limits.

Others argue that state and local lawmakers need to work with police departments to get them to comply. Whichever way it can be done, “agencies should be required to participate in the FBI’s database…it should be mandatory for all,” Steven Casstevens, the head of the International Association of Chiefs of Police, testified to the Senate Judiciary Committee on June 16. It’s a position the group has pushed for years, after a short-lived attempt at creating such a national database of use-of-force incidents in the late 1990s with support from the Bureau of Justice Statistics. “It should no longer be voluntary.”

“It’s ridiculous that I can’t tell you how many people were shot by the police in this country.”

Trump’s executive order is almost identical to a federal law that already exists – a provision in the 1994 crime bill signed by President Bill Clinton. Trump’s order directs the U.S. Attorney General to “create a database to coordinate the sharing of information… concerning instances of excessive use of force related to law enforcement matters” between federal, state and local agencies, which they “shall regularly and periodically make available to the public.” Similarly, the 1994 law directed the U.S. Attorney General to “acquire data about the use of excessive force by law enforcement officers” and that they “shall publish an annual summary of the data acquired under this section.”

And yet, while both these orders to the Justice Department – issued 26 years apart – mandate the collection and regular reporting of this data, the fact remains that there is no law requiring local police departments to provide it. Instead of finding ways to get local and state law enforcement agencies to comply with the 1994 federal law, the Justice Department expanded its “Police Public Contact Survey” in 1996, which released a report every three years after surveying a random sample of U.S. residents about their encounters with police. The latest report available, from 2015, surveyed 70,959 residents, but contained no comprehensive data on police use-of-force incidents.

The dearth of information has led to open frustration by the nation’s top law enforcement officials. “It’s ridiculous that I can’t tell you how many people were shot by the police in this country last week, last year, the last decade—it’s ridiculous,” then-FBI director James Comey admitted in February 2015.

In June of that year, the Obama Administration set into motion a separate nationwide initiative to fill that void. The FBI’s National Use-of-Force Data Collection, finally rolled out to great fanfare in November 2018, establishes a framework that allows police agencies to more easily report all incidents that result in death, “serious bodily injury” or the discharge of a firearm. “The opportunity to analyze information related to use-of-force incidents is hindered by the lack of nationwide statistics,” the FBI noted in its announcement of the program, calling it the first such “mechanism for collecting nationwide statistics related to use-of-force incidents” and promising it would “periodically release statistics to the public.”

The collection is intended to offer “a comprehensive view of the circumstances, subjects, and officers involved in such incidents nationwide” – exactly the kind of data that would be useful when trying to implement specific police reforms and identify which ones, such as changes in training or use of force policies, actually work.

The program convened its first task force for a series of meetings in 2016 and ran a pilot program in 2017. It established a help desk hotline and a dedicated email address for police officers submitting the data. It also developed a web application meant to simplify uploading cases in bulk, which was considered “user-friendly and intuitive” by officers who participated in the pilot program, according to an FBI report reviewed by TIME.

But despite all these efforts, as of March, less than 40% of police departments in the U.S. were enrolled in the FBI’s program and sharing their data, or 6,763 agencies covering 393,274 officers, out of a total 18,000 agencies, according to a federal release. According to the FBI pilot study reviewed by TIME, the first public report of the database’s statistics was “scheduled for March 2019.” But it never materialized, and the program still has not released a report as of June 2020. An FBI spokesperson tells TIME the first publication is now expected to be “this summer.”

“It’s not like you flip a switch and data flows in from 18,000 agencies.”

The 2017 pilot study listed a few reasons police departments would be reluctant to participate in the database, including the man hours required to submit the information and some technological hiccups. The report noted that the time burden on officers entering incidents into the system was roughly 38 minutes per incident. Some agencies reported that “it was a hassle handling the security constraints involved to enter the data collection portal.”

There needs to be recognition by those drafting legislation that for many police departments, especially smaller ones with limited resources, data collection requires hours of compensated time, says Hickman of Seattle University. “They made it a federal law but Congress did not appropriate any funds to actually do the job. It’s not like you flip a switch and data flows in from 18,000 agencies — it’s challenging,” Hickman says. “This kind of thing will tend to hit smaller agencies hardest, where in some cases, all personnel — including the Chief — are out on patrol and have little spare time to comply with federal data collections.”

There is widespread agreement that no matter what happens in Washington, for now the most effective legislation is likely to happen at the state level. Some states, including California, Colorado, Connecticut, Michigan and Texas, have passed various requirements to gather and report the data from their own police departments statewide, which allows many of them to report it up to the FBI database as well.

Robert Stevenson, the director of the Michigan Association of Chiefs of Police, tells TIME that state lawmakers pushing for more police transparency and use-of-force data were surprised when he told them that a federal program to collect this data already existed. “Many have never even heard of the [FBI’s] national database collection, even within law enforcement,” he said.

Lawmakers in Michigan agreed that the state’s police departments would mandatorily report to the federal FBI database and those numbers would also be released to the public. After getting the Michigan Sheriffs’ Association on board, the state went from 0% to more than 90% reporting use-of-force by police departments in 18 months, Stevenson said. The transparency measure that they included further helped build trust between the police and the community, which alleviated some of the pressure during the recent protests.

Police departments across the country should realize that collecting and analyzing this data serves everyone, including officers, Stevenson said. “If you don’t measure this data, how can you spot the problem? Now we’ll have the data to have that conversation, to actually lay it out [and say], ‘Look, we’re not massacring people left and right, and here’s where we can do better,’” he said. “This gives us the opportunity to have that informed conversation without the misperceptions and misinformation. It’s really important to our profession.”

For now, the police reform bills being debated in Congress — and their competing efforts to create a more complete police use-of-force database — remain in a stalemate. On June 24, Senate Democrats blocked debate on the Republican policing bill, which includes a proposal for use-of-force data collection focusing on police misconduct, condemning it for not going far enough in addressing racial inequality. The following day, Democrats passed a sweeping police overhaul bill in the House which includes a provision for a national database that would collect this information in more detail and make it public, as well as limit legal protections for the police.

Like its many predecessors, neither bill includes an accompanying legal mandate that could be tested in court to answer the question of whether police can be compelled to report their data to the federal government. Even so, longtime advocates of a national database nevertheless hope the end result will move the country towards finally having a fuller picture of where and how often U.S. police officers use force, and on whom.

“I have to be tentatively optimistic,” Alpert says. “I don’t want to be here in 10 years when we have another horrible event and everyone relives the same thing again. We gotta see progress. We at least have to be able to say, ‘Last time we got Step 1 and Step 2 done. What’s next?’”

—With reporting by Tessa Berenson/Washington

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Vera Bergengruen at vera.bergengruen@time.com