Just before 2:30 on the afternoon of Feb. 9, the Beatles got the signal to take their places for the first of two full dress rehearsals in front of a full, hysterical audience. If they seemed daunted at making their American debut, it didn’t show. They plugged in and waited patiently behind a curtain, exchanging relaxed, easy grins, as Ed Sullivan wandered onstage.

Sullivan was an improbable TV star. Stiff as cardboard and about as endearing, the 62-year-old emcee had, a profile in TIME said, as much charisma as “a cigar-store Indian.” He was painfully awkward in front of the camera, but he had an uncanny instinct for spotting talent and the ability to give it a national showcase. As such, he was a powerful star maker, to say nothing of an American icon. If you tuned in on Sunday nights, as a majority of TV watchers did, you were in for “a really big shew.”

If the audience left the dress rehearsals in ecstasy, the Beatles were anything but satisfied. “We weren’t happy with the … appearance,” said Paul, “because one of the mikes weren’t [sic] working.”

John’s vocals were muffled and often lost in the mix.

That evening, when the Beatles returned to Studio 50 for the live broadcast of The Ed Sullivan Show, George lit into Bob Precht, Sullivan’s son-in-law, who produced the show. The sound quality, he argued, was unacceptable.

In the midst of their heated exchange, visitors and dignitaries began streaming backstage to size up the four boys from Liverpool. Dizzy Gillespie, who was playing down the street at Birdland, “just stopped by to get a look at them,” as did various Capitol Records execs.

The Beatles were already feeling pinched by the crowd. But when Leonard Bernstein swept in with his daughters, babbling about a visit to Washington and “singing rounds with Jackie [Kennedy] at breakfast,” the boys had heard enough. John ordered the entire bunch chucked out and put the dressing room on lockdown.

As it was, the theater felt under siege. The crowd outside stretched over eight blocks, giving the place the revved-up energy of a Broadway opening. CBS had received more than 50,000 ticket requests; it seemed as though half that number were trying to get inside. Among those who did were Walter Cronkite’s and Jack Paar’s daughters, as well as Richard Nixon’s 15-year-old daughter Julie.

At 8 p.m. on Feb. 9, an unheard-of 60% of American TVs were tuned to CBS. The Beatles had caused a run on the airwaves that set all broadcast viewing records. Everyone wanted to have a look at the source of all that hoopla. How could four pop musicians—four boys from England—create so much excitement? It was beyond most American parents, who had watched the buildup with wary eyes.

The audience in living rooms may have been split down the middle, but the makeup of the theater belonged to the Beatles. As the credits rolled, the camera scanned the audience: wall-to-wall teenagers, mostly girls who were wound a bit tight. Passionate female fans were a staple of pop heartthrobs, but this gang was something else, on the edge of frenzy.

At last! The curtains swept open and America had its first look at the band—not in black leather and stagy scowls, not intimidating, as some had feared, but neatly groomed, all smiles, vaguely harmless: a pleasant surprise. The Beatles! Without hesitation, they launched right into a crisp if workmanlike version of “All My Loving,” a cut from their freshly minted LP, Meet the Beatles, which topped Billboard ’s charts the following week and remained there until it was knocked off by their second album.

More than a few eyes widened during their next number as the camera lingered on each of the Beatles’ faces and a crawl appeared at the bottom of the screen, identifying them by name. Paul McCartney, doe-eyed; George Harrison, jug-eared and stoic; Ringo Starr, grinning earnestly. When John Lennon got his close-up at the very end, an unexpected postscript revealed, “Sorry, girls, he’s married.”

That let a big cat out of the bag. Until that moment, John’s marriage had been not only hush-hush but hotly denied by the Beatles’ management. Band manager Brian Epstein had decided early on that the presence of a girlfriend—and especially a wife—would turn off the female fans. As such, Cynthia Lennon was forced to deny her marriage, even her name, to anyone who asked. She kept a low profile, never wore a wedding band, learned how to blend into the crowd. At shows, John would often stash her at the back of the hall, where she would watch like any other desperate fan. Moreover, they carefully avoided going out together in public.

If news of John’s marriage sucked the energy out of the performance for a few lovestruck fans, the boys quickly sent them airborne again. A clatter of drums erupted into “She Loves You,” jolting the audience. The last two numbers were even more riveting. Both “I Saw Her Standing There” and “I Want to Hold Your Hand” delivered on the promise of something thrilling.

The phenomenon unfolded in living rooms across the country. According to the A.C. Nielsen Co., the viewing audience was estimated at about 74 million people, reflecting a total of 23.24 million homes, a record for any TV show.

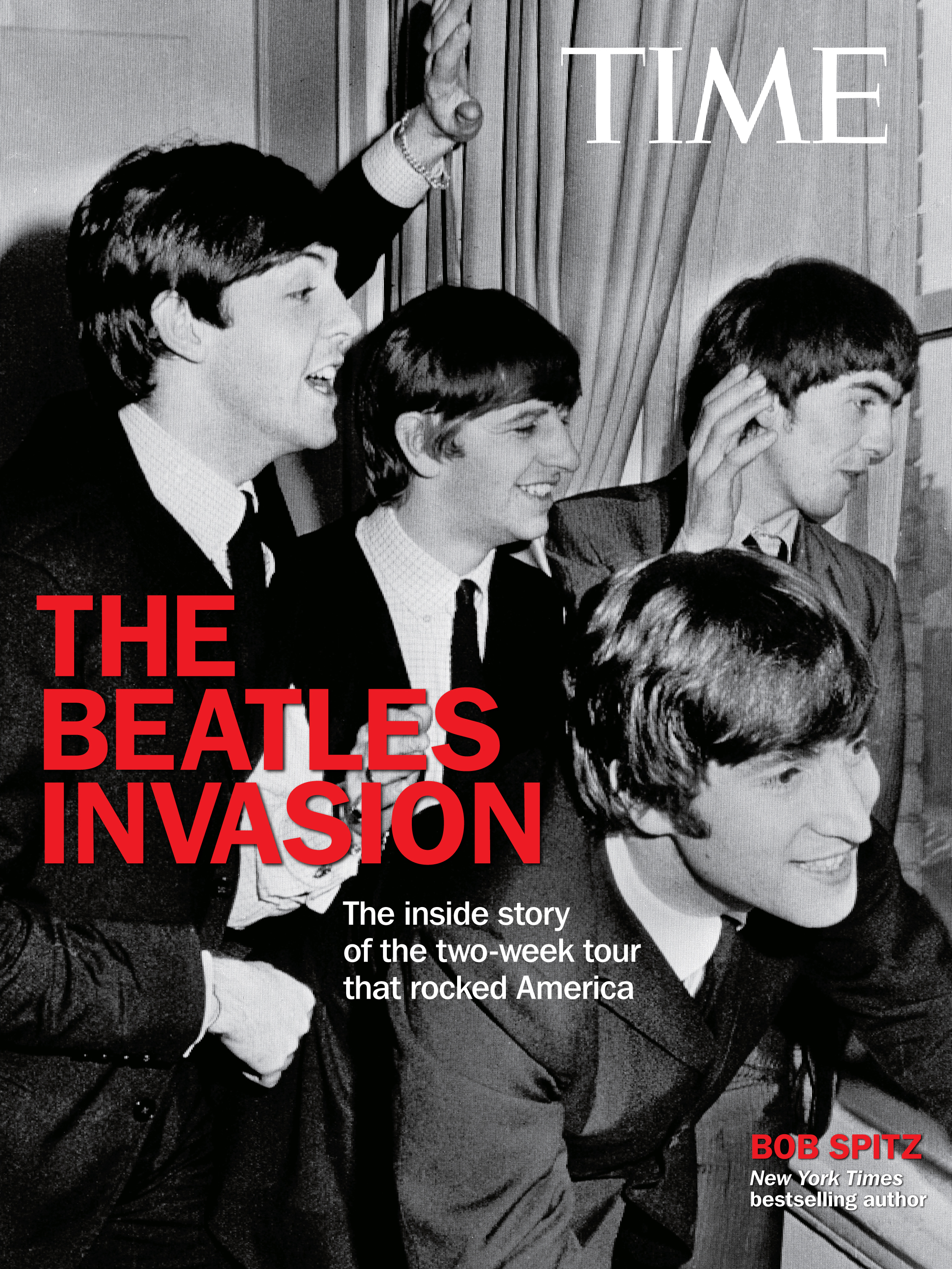

This is the third installment in a series of excerpts from the new TIME book, The Beatles Invasion: The Inside Story of the Two-Week Tour That Rocked America, by Bob Spitz. Copyright 2013, Time Home Entertainment. Available wherever books are sold.

First installment: The Beatles Invasion, 50 Years Ago: Friday, Feb. 7, 1964

Second installment: The Beatles Invasion, 50 Years Ago: Saturday, February 8, 1964

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com