As the United States faces an economic downturn driven by the worst unemployment rates since the Great Depression of the 1930s, it’s natural to make comparisons between how Presidents and the federal government managed that past economic crisis and President Donald Trump’s performance. While President Franklin Delano Roosevelt is the leader most associated with the Great Depression, he wasn’t the only man in the White House in that period—and the Depression is as much a lesson in what not to do as it is in what to do.

Almost a decade before the stock-market crash of 1929, a recession from January 1920 to July 1921 posed a great challenge to President Warren G. Harding, who entered the White House in March 1921. As prices fell—especially in agricultural produce, which tumbled by 50% as a resurgence of postwar European agriculture flooded markets—unemployment doubled as soldiers returning from Europe at the close of World War I looked for jobs. The Dow Jones Industrial Average fell nearly 50%. Harding had no idea what to do. He said he wished there was a book that could advise him on the economy, but even if there were one, Harding acknowledged he wouldn’t be able to understand it. Harding got lucky and the economic downturn righted itself without his intervention. Was Trump hoping for a similar outcome when he said in February that the coronavirus would disappear like a miracle?

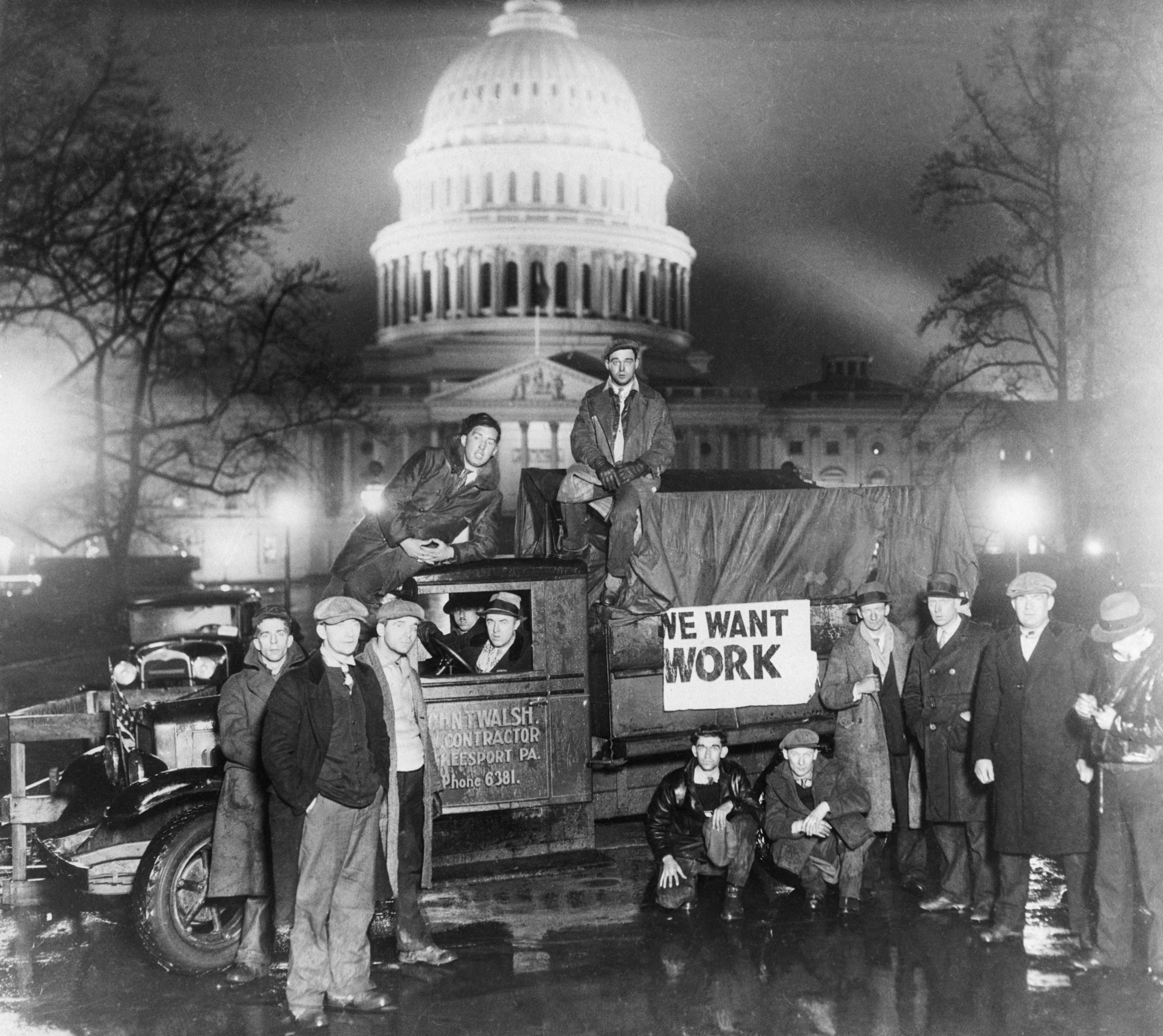

Herbert Hoover, who won the election of 1928 and had a reputation as a brilliant mining engineer and highly successful businessman, likewise struggled to respond to the stock market crash of 1929 and economic collapse beginning in 1930. The problem for Harding, Hoover and the Republicans who controlled Congress in the 1920s was an unyielding faith in free market capitalism. Convinced that the markets would automatically turn up, as they had in 1921, Hoover repeatedly urged the country to believe that prosperity was right around the corner. With conditions worse than ever and unemployment reaching 25% of the work force in 1932, Hoover lost the presidency in a landslide to New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

With a keen feel for the downcast national mood, Roosevelt said, we must be “prophets of a new order,” declared this country “demands action and action now,” and promised a New Deal. Roosevelt had no magic bullet to produce a quick economic revival but he broke new ground with 15 major pieces of legislation in the first hundred days of his term. It buoyed the country and launched the long road to a recovery. Though it would take mobilization for World War II to trigger a decisive economic upturn, Roosevelt’s leadership fostered renewed hope, with expanded job opportunities provided through public works projects, including dam-building and flood control that protected the environment, as well as projects for artists and writers. As important, his administration humanized America’s industrial economy with Social Security to insulate seniors from hardships, unemployment insurance and minimum wages and maximum hours that gave laborers unprecedented protections from market swings. On the strength of that success and his leadership in World War II, he won a record four presidential elections.

Donald Trump, who is no student of history, says that he has presided over the best economy ever in the United States and accomplished more in his first year and a half in office than any previous occupant of the White House. Never mind that the coronavirus has triggered a precipitous downturn with over 1.4 million Americans infected and more than 89,000 fatalities. In the beginnings of a reelection campaign in which Trump has to explain away nearly 15% unemployment, the worst since 1933, he is predicting a third-quarter resurgence and a fourth-quarter expansion that will carry over into next year.

Certainly no one can blame the pandemic itself on Trump, but he has overseen a slow and shortsighted response to the infectious virus. The Washington Post has cited more than 18,000 questionable statements he has made, including numerous outright lies. His credibility problem has played a significant part in making him the first president since polling began in the 1930s to go through almost four years without achieving 50% public approval—evidence that many people cannot square his rhetoric of alleged accomplishments and self-congratulation with public realities.

There is no question but that the country is facing a national crisis demanding an imaginative response like FDR provided with his New Deal. We can’t simply talk our way out of this challenge by ordering cities and states to reopen public businesses without an escalating death toll. The lackluster response to the economic problems of the 1920s shows just how cheap talk is in this kind of situation: leaving massive national problems to work themselves out without serious federal intervention only made things worse.

On the other hand, when Roosevelt addressed the economic collapse, he drew on the best minds in the country’s universities to help him. His experience as governor of New York, from 1929 to 1932, where he had already drawn on thoughtful men and women to aid in addressing the state’s economic ills, was a valuable advantage in formulating public policies. In addition, his paralysis from polio gave him a meaningful psychological advantage in mobilizing public support for his New Deal, as public understanding that he had recovered from the depths of his illness encouraged the belief that he could lead the nation to recover from the worst economic collapse in its history. He could, in other words, make America great again.

Today, Americans are once again facing the consequences of a failure to act, and a mistaken belief that a miracle solution is on its way. The past has already shown that there is a better way forward—but as the coronavirus crisis continues, it only seems more likely that FDR’s is not the history Trump plans to repeat.

Robert Dallek is the author of How Did We Get Here? From Theodore Roosevelt to Donald Trump, available May 26 from Harper.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com