The evening of May 14, 1970 had been a warm one in Jackson, Miss. At Jackson State College, a historically black institution located in the African American community just west of downtown, curfew for women was at 11:30 pm—but plenty of students were still hanging out at Alexander Hall, a women’s dormitory, a little after midnight. Leroy Kenter had just dropped off his girlfriend and was chatting with friends outside the west-wing entrance. Phillip Gibbs was talking to his sister Mary and her roommate through their window. Students were excited about the end of the year, with seniors anticipating graduation and a chance to go to work to support their families. As another student, Vernon Steve Weakley, recalled years later, “That night was a quiet night. Kids were outside having a good time. . . . Music was blasting.” After all, Alexander Hall was “where all the girls are.”

On the other end of campus things were not so relaxed. The night before, police had cordoned off Lynch Street, a busy road through the center of the school. The thoroughfare had long been a source of tension as white commuters sped through campus, sometimes endangering pedestrians or hurling racial epithets, and students had repeatedly protested this abuse to no avail. The previous evening a group of young people had thrown rocks at passing motorists, leading to the closure of the street. Though city and state law enforcement considered entering the campus, the mayor had held them back, de-escalating the situation. The next morning the campus was calm, and students went about the business of classes and upcoming exams.

That afternoon, the president of the college asked that traffic again be halted to avoid further unrest, but the city refused. Someone again threw rocks at motorists. There was disagreement later about who had initiated the unrest, and why. Some claimed it was local youths, “corner boys.” Others maintained students had acted to draw attention to their concerns over the war, the draft and student rights. Still others suggested it was the result of rumors that Charles Evers, the activist mayor of nearby Fayette, had been murdered along with his wife. Many were uncertain about the cause. With the renewed trouble, the city again closed the street. At this point, a group of young people commandeered a dump truck from a neighboring construction site, drove it onto Lynch Street and set it afire.

With a fire truck called to the scene, the Mississippi Highway and Safety Patrol (MHSP) and the Jackson city police arrived as well; both were there to protect the firefighters. Law enforcement’s presence only angered the crowd. When the fire was doused, rather than leaving, the officers turned and marched, inexplicably and against their orders, up Lynch Street toward the center of campus.

When they reached Alexander Hall, a few blocks away, they turned to face the dorm and the students there, and leveled their weapons at them. When a bottle hit the pavement nearby, the officers opened fire, unleashing a 28-second barrage that killed two young people, including Phillip Gibbs and James Earl Green, a local student just days away from his high-school graduation. Twelve other young people were injured, including Leroy Kenter and Vernon Steve Weakley. Fifty years later, though the nation retains a vivid memory of the state violence at Kent State ten days earlier, the Jackson State shootings have been largely forgotten. This amnesia carries real consequences.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Conflict between local law enforcement and Jackson State students was nothing new in 1970. Founded in 1877 to serve those recently freed from slavery, the institution had always struggled against white supremacists seeking to limit African American access to education. So, over the decades school administrators had worked hard to build an institution that could serve its students well while also placating the white community with tight controls on students’ behavior. When the civil rights movement exploded in the 1960s, students who joined in protests faced expulsion by the college and harsh criticism in the local white press—censure that framed them not as activists but as dangerous criminals. For example, when the police shot and killed local civil rights activist Benjamin Brown during a disturbance near campus in 1967, the Jackson Clarion-Ledger not only emphasized his multiple arrests, failing to note that he had not been involved in the unrest, that he was shot in the back while trying to escape the turmoil, or that his previous run-ins with law enforcement had been the result of his activism.

Nor was this situation confined to Jackson. By 1970 this law-and-order perspective had swept the nation, pushed by President Richard Nixon. Though the language of his 1968 campaign carefully veiled any explicit racial implications, both the candidate and many white voters understood its discriminatory undertones. As his adviser John Ehrlichman wrote in his diary, the “subliminal appeal to the anti-black voter was always present in Nixon’s statements and speeches.” Nixon rode this rhetoric to the White House. While the fear on which it capitalized was as much about losing the social and economic advantages produced by the system of white supremacy, it was frequently expressed as a concern about black criminality and pitched as a call for law and order.

At Jackson State, the outcome of this rhetoric became clear. By 1970 the campus was changing, as a new college president made space for student views and voices, and racial consciousness was more openly expressed. But despite the efforts of civil rights activists, the MHSP remained an all-white force and the Jackson police had added only a handful of black patrolmen to its ranks by 1970. They brought the city’s armored tank to campus and carried weapons better suited to a military operation than crowd control. Without cause, they confronted an innocent crowd, uninvolved in the earlier unrest, with loaded weapons. After the barrage they failed to offer aid to the wounded or dead. And recorded communications with headquarters as well as eyewitness accounts reveal that they routinely adopted the worst racial epithets when talking to the students or reporting on the carnage.

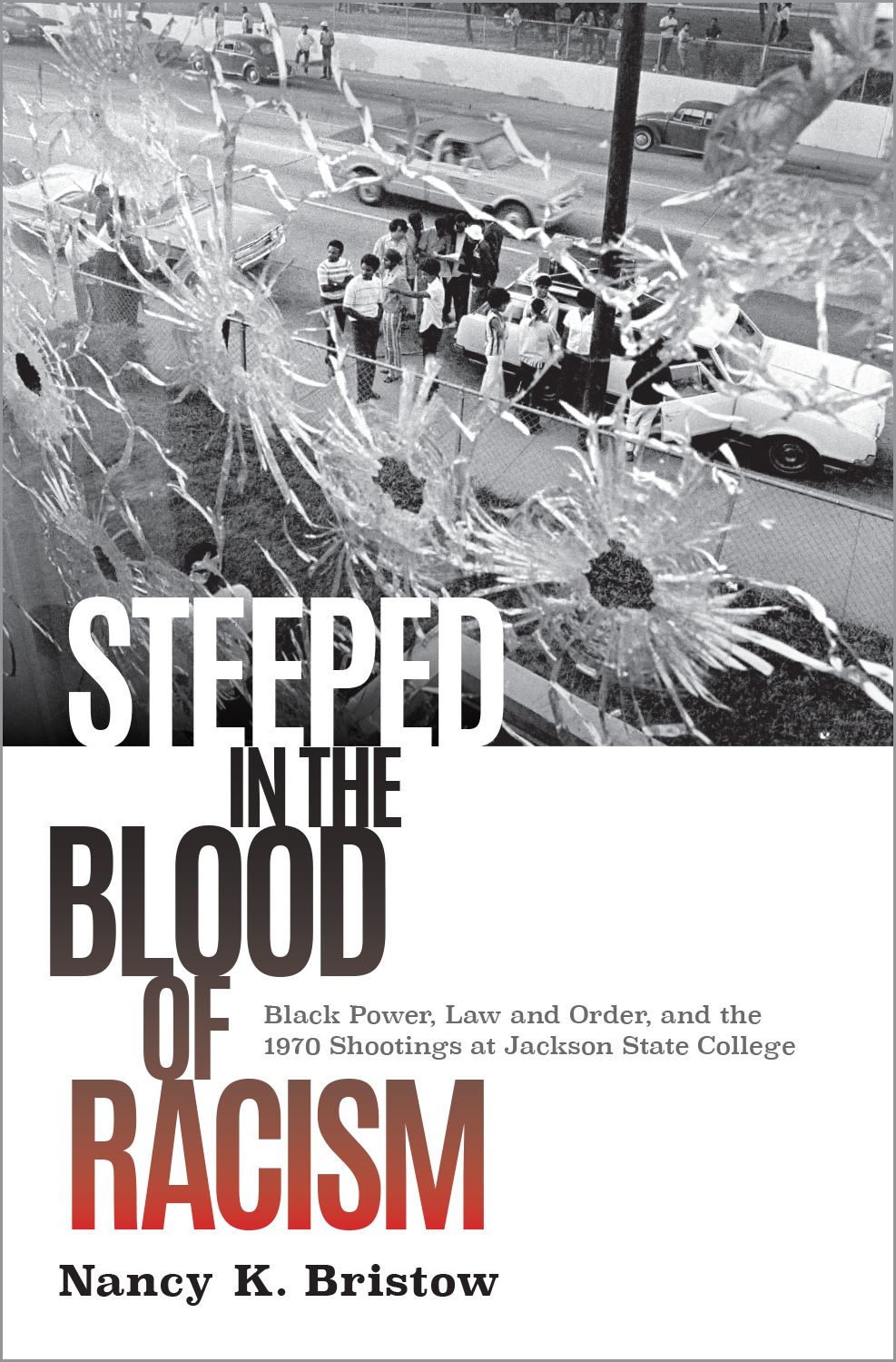

In the aftermath, the highway patrol and the police claimed falsely that their lives had been threatened by the students and concocted a story about a sniper in the dormitory. At the time of the shooting, all of the students had retreated from the street and were separated from the officers by a chain link fence. No evidence of a sniper was ever discovered, and the officer’s actions violated basic protocol as they sprayed the building and the students out front with over 150 rounds of ammunition, marking the sides of Alexander Hall with more than 400 bullet or buckshot marks.

Though the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest found the shootings “an unreasonable, unjustified overreaction,” and recognized that “racial antagonisms” were central to the events, two grand juries—one county, one federal—would fail to indict any members of law enforcement. When some of the wounded and the families of the slain brought a civil suit, the defense framed them as threatening lawbreakers, and defended the officers as heroes protecting their community. The all-white jury found for law enforcement.

In the five decades since the shootings, the problem of police violence against young men of color has persisted. African American men and boys are two-and-a-half times as likely as their white counterparts to face death by police shooting. The rate is highest for young black men in their mid-to-late 20s and constitutes a leading cause of death for this demographic. In recent days we have seen once more the horrors of this kind of white on black violence, as news of the killing of Ahmaud Arbery has gained national attention. Though in this case the men charged with his killing are a former policeman and his son, the same dynamics are in play and the investigation into the killing was delayed by months. None of this is unfamiliar to African Americans, who from childhood learn the danger posed by law enforcement; today, in the midst of a global pandemic, many African American men are afraid to wear masks in public, fearful that this will enhance their chances of dying at the hands of police. But even headline-making cases are dismissed by too many white Americans as one-off incidents. Confronting the history of events like the Jackson State shooting would make such a stance much more difficult to support.

At the 50th anniversary of the shootings at Jackson State, we owe it to those who suffered as a result of that night to remember them—and to use that understanding to see how the crisis of racial injustice continues.

Nancy K. Bristow is the author of Steeped in the Blood of Racism: Black Power, Law and Order, and the 1970 Shootings at Jackson State College, available now.

Correction, May 15

The original version of this story misstated where Charles Evers was mayor. He was mayor of Fayette, not Fayetteville.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com