Walter Frederick Mondale, one of the most influential vice presidents of his era, died on Monday in Minneapolis, according to multiple reports. He was 93.

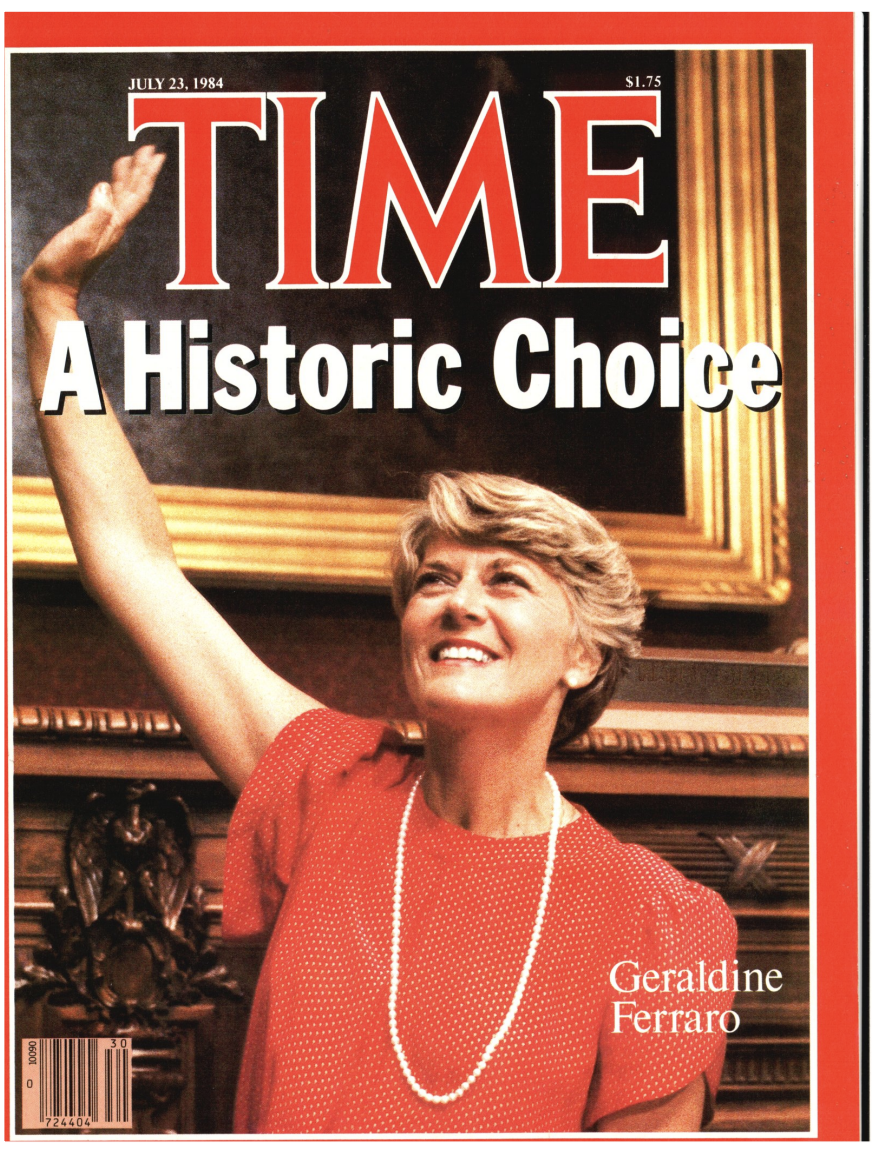

Mondale served as the 42nd Vice President of the United States under President Jimmy Carter from 1977 to 1981, acting as a trusted confidant to Carter while helping guide the administration’s policies. He also had his own memorable run for president in 1984, making history by choosing Geraldine Ferraro as his running mate, creating the first presidential ticket from a major party that included a woman.

Mondale — who went by the nickname “Fritz” — was a pillar of Minnesota Democratic politics for a generation, and came to national prominence in 1976 when then-Georgia Governor Carter selected Mondale as his running mate. The press nicknamed the pair “Fritz and Grits,” and Mondale proved to be a helpful asset, performing well in the first-ever televised vice presidential debate against the Republican candidate, Kansas Sen. Bob Dole.

Carter said in a statement obtained by the Associated Press Monday night that he considered Mondale “the best vice president in our country’s history.” He added: “Fritz Mondale provided us all with a model for public service and private behavior.”

After Carter defeated Republican incumbent Gerald Ford and became President, he granted Mondale an office in the West Wing and the pair settled into a close working relationship. They held private lunches every Monday where they could troubleshoot and speak freely, and Mondale even received the same daily intelligence as Carter and regularly met with senior staff. He helped shape policy and Cabinet appointments, functioning as a “generalist” whom Carter could turn to on most issues.

Their close bond endured in the decades after leaving office, and during a 2015 dinner honoring Mondale, Carter said they never had a fight while he occupied the Oval Office (although Mondale reportedly disagreed with Carter’s infamous “Crisis of Confidence” speech). “What Fritz and I did together was historic,” Carter said at the time. “It changed the basic structure of the executive branch of government to bring in the vice president as a full partner of the president.”

“We understood each other’s needs,” Mondale also said about Carter, according to the Senate historical office. “We respected each other’s opinions. We kept each other’s confidence.”

Mondale was born in Ceylon, Minn., on Jan. 5, 1928 to a Methodist minister father and a music teacher mother. He graduated from the University of Minnesota in 1951 and enlisted in the Korean War as an Army corporal before returning home to enroll in law school, graduating in 1956. In the summer of 1955 he met his future wife, Joan Adams, on a blind date; they were married by December.

Mondale swiftly gained traction in the Minnesota Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party, becoming the protégé of Senator-turned-Vice President Hubert Humphrey. He was appointed Minnesota’s attorney general at just 32, making him the youngest attorney general in the country at the time. When Humphrey left the Senate to become Lyndon Johnson’s Vice President in 1964, Minnesota Governor Karl Rolvaag appointed 36-year-old Mondale to fill the open Senate seat. Mondale then won a full Senate term in 1966.

According to the U.S. Senate historical office, the young Senator was “admired, trusted, and promoted by other politicians,” and was known as a level-headed operator who rarely became emotional. He wore a coat and tie to most events, and Humphrey once remarked that “the thing that is most evident about Mondale … is that he’s non-abrasive. He is not a polarizer.”

While in the Senate, Mondale sponsored the Fair Warning Act, which required car manufacturers to tell consumers about defects. He also co-authored the Fair Housing Act, which aimed to end discriminatory housing practices. He supported the Vietnam War throughout Johnson’s presidency, but changed his position in October of 1969, after Richard Nixon became President. In 1973, Mondale co-sponsored the War Powers Resolution, which limited the President’s ability to commit the U.S. to war without Congressional approval. According to the Senate historical office, “Mondale played a transitional role in the Democratic Party, seeking to bridge the generational and ideological divisions that racked the party during and after the 1960s.”

Mondale served in the Senate for more than a decade before Carter tapped him as his running mate, and after their victory he quickly settled into the White House, remaining there for the next four years. Although the duo aimed for a second term, Republican California Gov. Ronald Reagan won the presidency in 1980 after Carter faced issues including inflation at home and the Iran hostage crisis abroad.

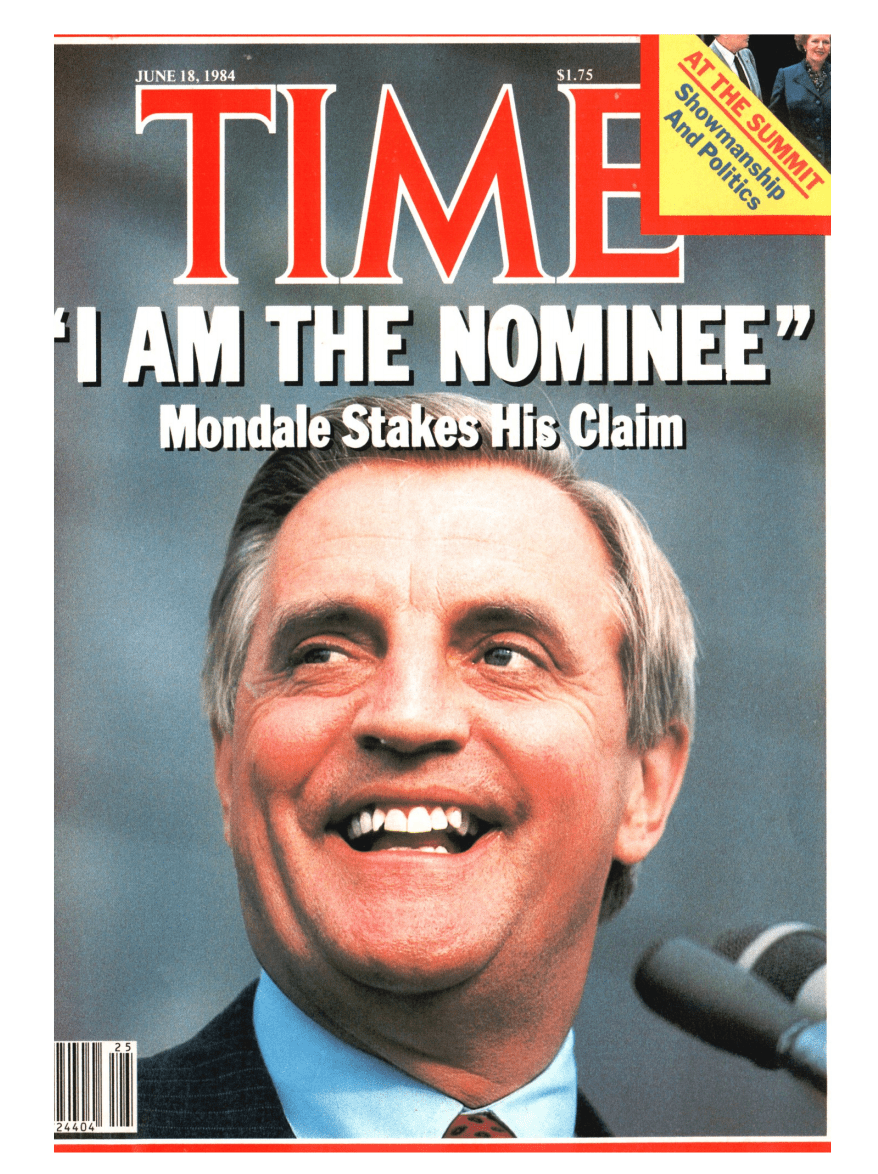

After their defeat, Mondale returned to Minnesota to practice law and began to prepare for a presidential run of his own. But when he entered the Democratic race, he faced tough competition. Reverend Jesse Jackson and Colorado Sen. Gary Hart also ran for the Democratic nomination, and after a heated primary — in which Mondale famously asked Hart “where’s the beef” during a debate, parodying a popular commercial — Mondale eventually won and went on to face Reagan in the general.

Then, on July 12, 1984, Mondale made history. In an effort to inject life into his campaign, he selected New York Congresswoman Geraldine Ferarro as his running mate, making her the first woman to appear on a major party’s presidential ticket. As TIME reported following the announcement, “Walter Mondale has never experienced a day like this before. People were actually crying. He has never had this kind of response, this same kind of excitement.”

“This is an exciting choice,” Mondale said as he announced Ferraro. “Our founders said in the Constitution: ‘We the people’—not just the rich, or men, or white, but all of us.”

But excitement around Ferraro did not save Mondale’s campaign. The economy had begun to rebound during Reagan’s first term, and the sitting President took full credit for it. When Mondale accepted his party’s nomination he also infamously pledged to raise taxes, saying, “Mr. Reagan will raise taxes, and so will I… He won’t tell you, I just did.” As Theodore H. White wrote in TIME in 1984, “Where Reagan sought to soothe and cheer Americans, Mondale tried to puncture their complacency with warnings of impending doom and taxes.”

Mondale ultimately lost the presidential race in the biggest Republican landslide in U.S. history: Reagan won 49 states and 525 electoral votes, while Mondale only carried his home state of Minnesota and Washington D.C., winning just 13 electoral votes.

After his stinging loss, Mondale once again returned to practicing law. While some thought the 62-year-old would run for Senate again in 1990, he instead chose to sit it out, explaining that he believed “it’s time for other candidates to step forward.”

But his time in politics didn’t fully end: Mondale served as ambassador to Japan under the Clinton administration from 1993 to 1996. He also mentored rising Minnesota politicians, including 2020 Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Amy Klobuchar. And in 2002 he accepted the nomination to run for his old Senate seat, after the Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party’s candidate Senator Paul Wellstone died unexpectedly in a plane crash less than two weeks before election day. Mondale narrowly lost the race to Republican St. Paul Mayor Norm Coleman. “At the end of what will be my last campaign, I want to say to Minnesota, you always treated me well, you always listened to me,” Mondale said in his concession speech.

Mondale is survived by sons Ted Mondale, a former Minnesota state senator, and William Mondale, former assistant attorney general of Minnesota. His wife, Joan, died in 2014 at age 83, and his daughter, Eleanor Poling, died from brain cancer in 2011 at age 51.

“I entered politics young, impatient, and full of confidence that government could be used to better people’s lives,” Mondale wrote in his 2010 memoir, The Good Fight. “My faith has not dimmed. But I also came to understand that voters didn’t simply put us in office to write laws or correct the wrongs of the moment. They were asking us to safeguard the remarkable nation our founders left us and leave it better for our children.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Madeleine Carlisle at madeleine.carlisle@time.com