When Alexander Paine Wilson sees the aardvark for the first time, he’s annoyed. This isn’t a surprising reaction for the young Republican Congressman — he’s easily irritated. That morning, he’s already aggrieved by the broken air-conditioning in his townhouse (on a particularly hot day in Washington, D.C.) and the fact that he has no wife or children, which makes his reelection odds less favorable than he’d like. When a giant box with a taxidermied aardvark arrives, Wilson suspects he knows where it came from. And he’s not happy.

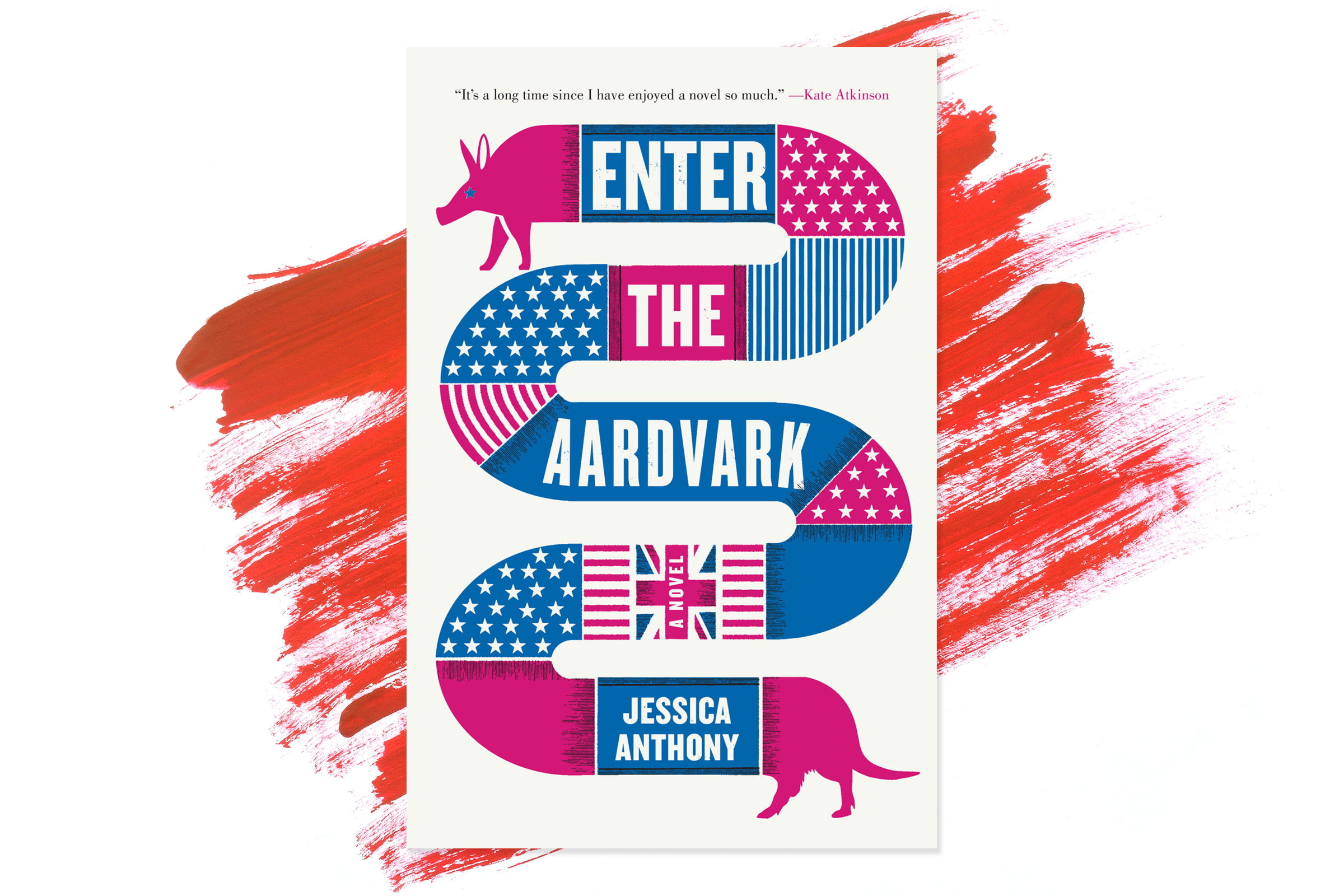

Enter the Aardvark, Jessica Anthony’s second novel, flips between modern-day D.C. and 19th century England, when the aardvark was first found by a naturalist who offered it to his friend, a taxidermist. Quickly, Anthony reveals that these men had more in common with Wilson than he’d like to admit: they were gay and forced to hide their sexuality. The aardvark served as a totem of their forbidden love — and its arrival threatens to unravel Wilson’s carefully constructed image.

The politician’s narration, which is written in the second person, captures his gnawing agitations with the world, which quickly fester to anger. It’s this rage that Anthony methodically — and hilariously — picks apart through her protagonist’s misguided obsession with how he’s perceived by others. Wilson desperately wants to be someone he isn’t, and thinks he can buy his way into becoming the next Reagan. When preparing to confront the man he thinks sent the animal, he seethes as he dons his political costume: “Motherofgod, you think, what a pain in the ass, as you dress yourself, head to toe, in light casual summerwear from J. Crew.”

Though Enter the Aardvark is certainly satire, Anthony’s depiction of Wilson’s repressed sexuality cuts beneath the surface. Her dissection of Wilson’s political beliefs, particularly his anti-abortion stance, isn’t just sharp commentary on polarization, identity and power in the U.S. It’s also a poignant examination of what happens when we deny ourselves the ability to love and be loved.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Annabel Gutterman at annabel.gutterman@time.com