Meet the people and groups who are fighting to level up.

The Rev. William J. Barber II

Speaking up for the poor

The newsmaking actions of Rev. William J. Barber II are founded on the idea that being a person of faith means fighting for justice—whether by working beside a conservative mayor to protest the closing of rural hospitals or by calling for an NAACP boycott of the state in response to the legislature’s actions… —Mary C. Curtis

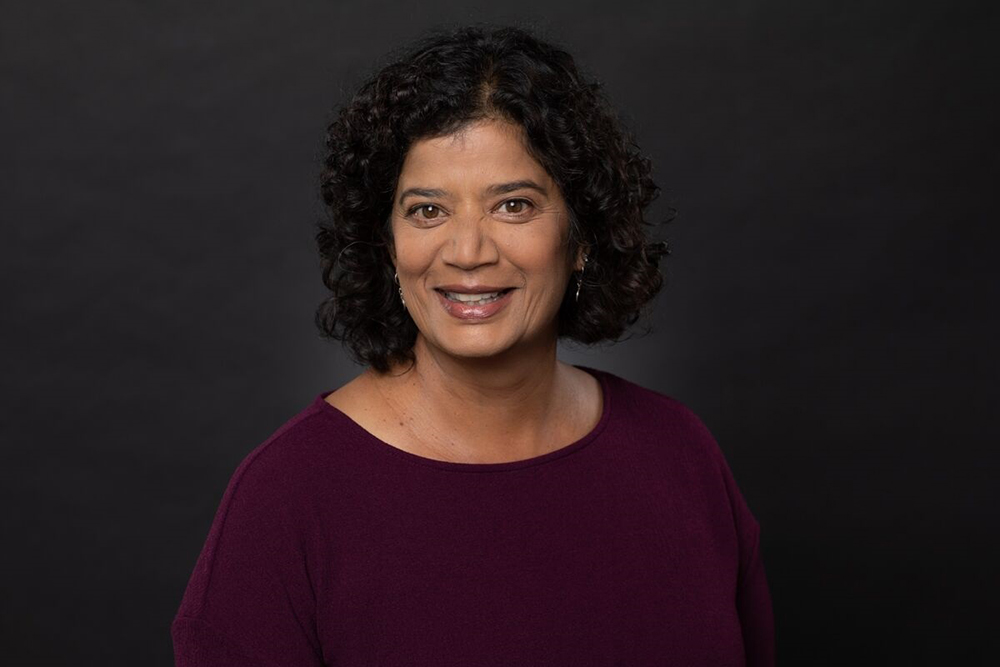

Angela Doyinsola Aina

Empowering black mothers

The U.S. spends much more on health care than any other developed country does, and yet women in the U.S. are dying of -pregnancy-related causes more than they used to and more than in other developed nations. This problem is particularly dire for African Americans, who are three to four times more likely than their white counterparts to suffer -pregnancy-related deaths. Black Mamas Matter Alliance (BMMA), co-founded by Angela Doyinsola Aina, launched in 2016 to address these huge disparities; the group worked with Congress to launch Black Maternal Health Week, now held each April. “What is perpetuating these adverse health outcomes is structural racism and gender oppression,” says Aina, 36.

This year, Aina is drawing on her own background in public health to ramp up BMMA’s research efforts and to promote the use of midwives and doulas, who she says can be critical resources for communities that have historically fraught relationships with the U.S. medical system. The World Health Organization named 2020 the “year of the nurse and midwife,” and Aina hopes this increased attention will help lead to more investment in black women–led health programs. “Those are the initiatives that work best,” she says, “in communities that are most impacted by health disparities.” —Abigail Abrams

Greg Asbed, Lucas Benitez and Laura Germino

Justice for farmworkers

The Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) began in the 1990s as a collection of Florida-based farmworkers organizing to fight long-standing labor abuses. Lucas Benitez, 44, one of the co-founders, tells TIME via translator that the CIW’s main goal is to correct the imbalance of power between the food industry and its workers that “allowed for the abuses that we were facing.”

In 2011, the CIW launched the Fair Food Program (FFP), an agreement between the CIW, farms and retail food companies that pledge to purchase produce only from growers who agree to a code of conduct with enforceable consequences, ensuring the civil rights of farmworkers are protected. Megabrands such as McDonald’s and Walmart are among the participating buyers, and the group is targeting holdouts: on March 10–12, the CIW will lead a series of marches through New York City to put pressure on Wendy’s to join.“We realized that if we were going to actually address the poverty and the abuses on the farm,” says Greg Asbed, 56, another co-founder, “we’d have to look beyond the farm for the answer.” —Madeleine Carlisle

Dina Bakst

Helping working women

For many American women, especially low-wage workers in physically demanding fields, having kids means jeopardizing their jobs—so much so that they may be forced to choose between a paycheck and a healthy pregnancy. That situation, says Dina Bakst, “snowballs into lasting economic disadvantage.”

As co-founder of the legal advocacy organization A Better Balance, Bakst, 47, represents women who lose their jobs while pregnant. She’s championing federal legislation advancing in Congress this year to help pregnant women and new mothers get fair treatment at work: the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act and the PUMP for Nursing Mothers Act would, respectively, require employers to make reasonable accommodations for pregnant employees, and make it easier for breastfeeding moms to pump at work. At a time when there are more women than men in the U.S. workforce, Bakst says implementing fair work-life standards—including pregnancy accommodations, paid sick days, paid family and medical leave, and quality affordable childcare—is more important than ever: “It’s absolutely essential for gender equality and for our nation’s economic security.” —Katie Reilly

William C. Bell

Fixing foster care

The roughly 437,000 U.S. children in foster care are more likely to drop out of high school compared with peers who live with family, and children who age out of the system are more likely to face homelessness, unemployment and incarceration. Foster care, while designed to help children in need, also exacerbates existing inequalities: poorer families are more likely to have a child removed from the home, and many advocates argue that’s because the child–welfare system scrutinizes signs of poverty, labeling it child neglect.

William C. Bell aspires to an America with as few children in foster care as possible. As president and CEO of Casey Family Programs, Bell, 60, was one of the strongest advocates for the Family First Prevention Services Act, landmark bipartisan legislation that aims to keep more families together. The law, which took effect in October, allows states to use federal funding to help struggling parents before resorting to putting children in foster care. “If we can get more children being raised in a family-like setting, either with their parents or extended family,” Bell says, “it bodes well for what happens in this country in the long run.” —K.R.

Kat Calvin

Making IDs more accessible

Millions of U.S. voters don’t have a photo ID, and yet—with a wave of new laws in the run-up to the 2016 election—about two-thirds of states require some kind of identification to vote. Critics say those laws -suppress the votes of vulnerable Americans who cannot take on the cost or the burden of getting an ID. So in 2017, Kat Calvin, 36, founded Spread the Vote, a nonprofit dedicated to helping people secure IDs. It’s now active in 12 states, with more than 600 volunteers. As the 2020 election approaches, the organization reports having helped over 4,500 people obtain IDs; more than 77% of them have never voted before.

But Calvin’s mission has grown beyond the ballot box. A large percentage of food banks and homeless shelters also require IDs. You also need an ID for legal employment. “Just basic survival is almost impossible without one,” she says. A common response that Calvin hears from her clients: “I’m a person again.” —M.C.

Patrisse Cullors

Improving criminal justice

The activist and educator Patrisse Cullors is best known for a movement that swept the entire U.S.: in 2013, along with Alicia Garza and Opal Tometi, she co-founded Black Lives Matter. Recently, though, her focus has been more local. Her new plan, the “Yes on R” campaign, supports a ballot initiative—Measure R—to reform the Los Angeles County jails, buttress oversight of the sheriff’s department, and provide treatment and mental-health care for those incarcerated in L.A. Measure R will be voted on this March, thanks to more than a quarter-million signatures getting it on the ballot. “We have to have strong communities, strong cities and strong counties,” says Cullors, 36. And, she notes, local work can lead to something bigger: people from across the country have reached out to her about implementing something similar to Yes on R in their own cities. —Josiah Bates

Step Into History: Learn how to experience the 1963 March on Washington in virtual reality

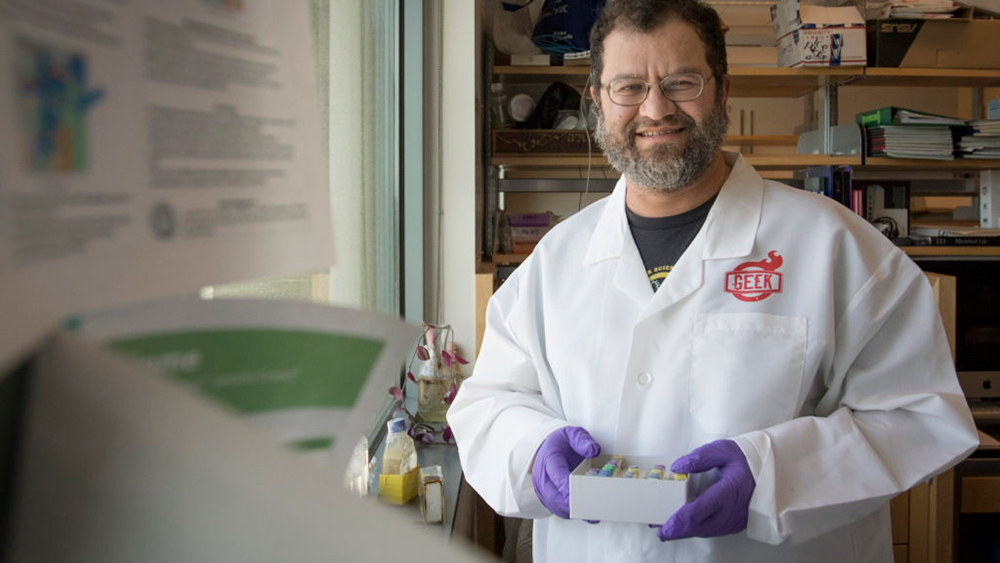

Jonathan Eisen

Seeking science diversity

Jonathan Eisen, professor at the genome center at University of California, Davis, knows he’s an unlikely champion for female representation at scientific conferences. But he also knows someone needs to point out the dearth of women who are speakers at these events. Since Eisen, 51, first vented his frustration with the problem in a 2012 blog post, his social-media feed has called out scientific gatherings that disproportionately feature male scientists.

His posts make him the target of criticism from colleagues, and conference organizers have threatened to bar him from their future meetings. But he willingly bears the brunt of that backlash, and has received grateful feedback from men and women who appreciate his serving as the lightning rod for any fallout. Now, Eisen says that around a third of his posts highlighting gender bias at conferences come from other scientists.

On his blog, he also includes advice for how to run a more diverse meeting that includes not just a better balance of men and women, but people of color and scientists at different stages of their careers as well. “We can fix this,” he says. “And no doubt things have been changing. But also without a doubt, it’s not enough.” —Alice Park

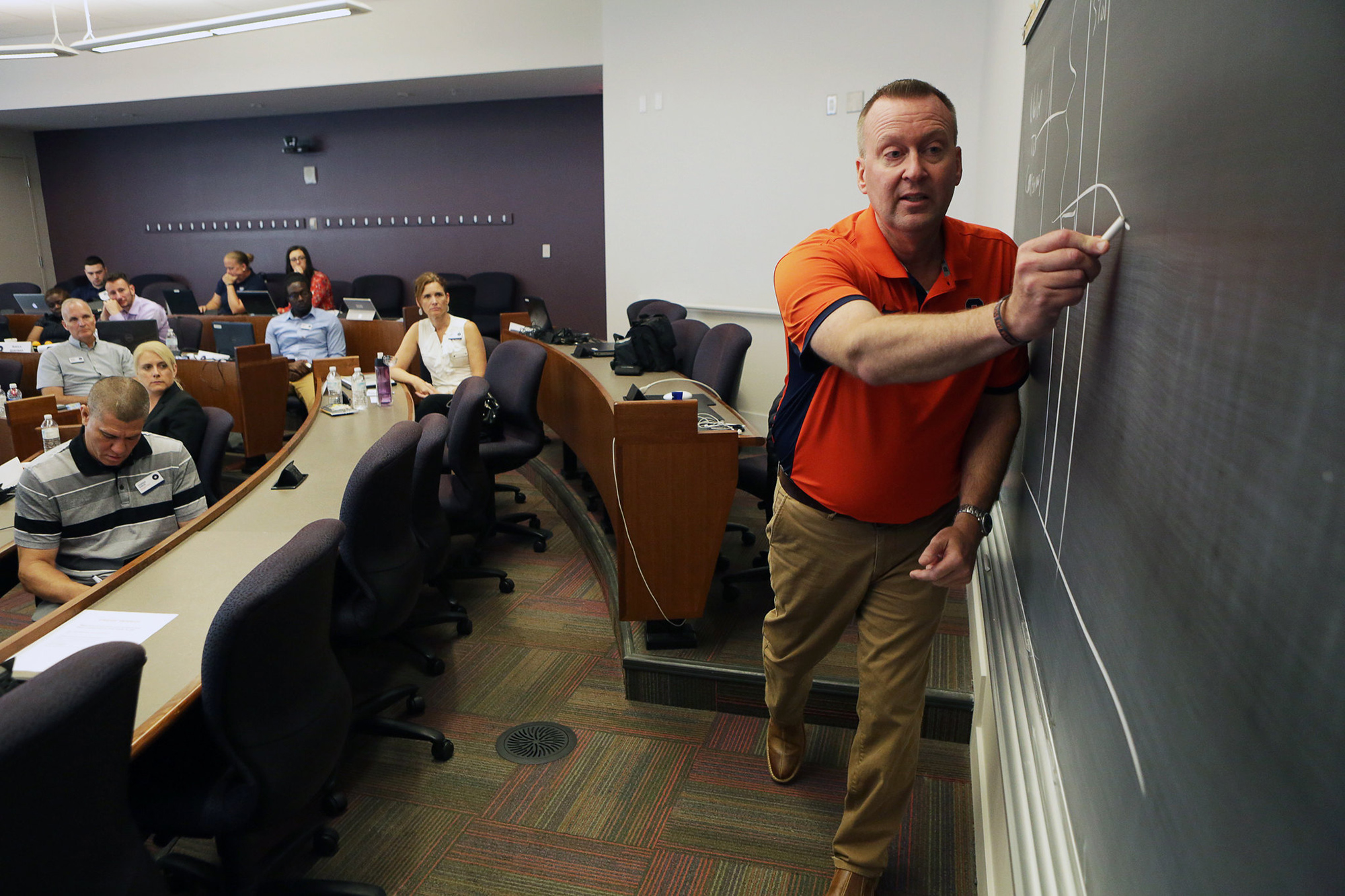

Michael Haynie

Meeting veterans’ needs

When Michael Haynie left the Air Force after 14 years to teach business at Syracuse University, he was shocked by how little attention the people in his new world paid to the challenges facing veterans. In 2011, recognizing that someone had to step up, he founded Syracuse’s Institute for Veterans and Military Families (IVMF).

Veterans need attention—-especially as they transition from military to civilian life—so, in addition to research and advocacy, the institute provides free professional training programs to veterans and their families, and has served more than 132,000 since its founding, reaching more people in 2019 than any other transition program for U.S. veterans. What began as a staff of three has grown to more than 100 -full-time employees operating around the world. Come April, Syracuse will open the National Veterans Resource Center, a $62.5 million facility, to be the center of IVMF’s operations. For Haynie, 50, the building is about “planting a flag.”

“It’s about signaling to the rest of the higher-education community that these issues matter,” he says, arguing that America has a moral obligation to ensure that “we get to a place where folks we send off to war don’t come home and feel like an outsider in the same society that they went off to defend.” —M.C.

Nelson Luna and Whitney Stephenson

Integrating schools

Nearly 66 years after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled racial segregation in public education unconstitutional, more than half of the nation’s students still attend largely segregated school districts. In New York City, one of the country’s most segregated school systems, students are leading the fight to change that.

Nelson Luna and Whitney Stephenson, both 19, founded Teens Take Charge at their public charter high school in 2017 to campaign for integration. Since then, Teens Take Charge activists from more than 30 high schools have led walkouts and a City Hall sit-in, protesting the uneven distribution of resources in the system and the admissions process for the city’s specialized high schools, which enroll mostly white and Asian students.

Now first-generation college sophomores, Luna and Stephenson are still involved in that advocacy, though a team of current high school students, along with fellow student-led activist group IntegrateNYC, have pushed the movement forward. This spring, both groups are planning a citywide school boycott, echoing a 1964 anti-segregation boycott by about 460,000 New York City students.

“Although it may look different in this era,” Stephenson says, “it’s still school segregation.” —K.R.

Athletes of the WNBA

Fighting for a fair share

WNBA players have to fight two battles—one on the court, and the other off court. This is about more than pay; it’s about recognition for their hard work as athletes. Here are these women, playing the same sport we are, receiving less than we do. And not just in pay—it’s about being seen as an athlete, regardless of gender. Pay disparity isn’t only a women’s issue; this is a human-rights issue. These women are our peers who, just like those of us in the NBA, inspire the next generation… —Enes Kanter

Shireen McSpadden

Against ageism

Last year, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed an executive order that would create a “Master Plan for Aging,” acknowledging that the state’s over-65 population is projected to grow from 5.5 million in 2016 to 8.6 million by 2030—and that the increased elderly population will require attention and investment. Shireen McSpadden, the executive director for San Francisco’s Department of Disability and Aging Services, is central to the effort. In late 2019, McSpadden, 56, was a key part of the formation of Reframing Aging San Francisco, a campaign that aims to empower older adults in the city. She sees ageism as an equity issue, one that leaves behind essential community members simply because of negative assumptions. “As we age in community, we need to continue to be a part of society,” she says. “That’s what keeps us going as humans.” —Mahita Gajanan

Simran Jeet Singh

Fairness for all faiths

Growing up Sikh in San Antonio, Simran Jeet Singh felt “highly visible yet entirely unknown,” he says. He was a high school senior when a streak of hate crimes against Sikhs swept the U.S. in the months after 9/11, and he realized that “ignorance is actually a matter of life and death.” He’s turned that drive into a career as a scholar and advocate for religious freedom. On his podcast Spirited, he interviews prominent figures about spirituality, and he has a regular column for Religion News Service. Notably, he’s written about the idea of “religious supremacy.” Just as white supremacy is a dangerous thread in American life, he argues, so is the idea that one religion is superior. For Singh, 35, religious equality requires challenging the assumption that Christianity is the default. “Then,” he says, “we can actually create an even playing field for people of different traditions.”

On Aug. 25, he’ll release a children’s book, Fauja Singh Keeps Going, the true story of a Sikh man who was the oldest person to run a marathon. “This has been my dream,” he says. “Growing up, we never saw a Sikh character in a children’s book.” But his children will. —M.C.

Chase Strangio

Demanding LGBTQ rights

Transgender communities in the U.S. are fighting for rights across all facets of life, from demanding access to restrooms to protesting laws that aim to curb their medical care. And Chase Strangio, who serves as the deputy director for transgender justice with the ACLU’s LGBT & HIV Project, is leading many of those battles. One was in South Dakota, against a bill that would make it a crime for doctors to give hormone therapies to trans youth; the legislation was defeated in committee in February. Strangio, 37, says the stakes couldn’t be higher; per Human Rights Campaign figures, at least 26 trans or gender-non-conforming people, over 90% of whom were black trans women, were killed by violence in 2019.

For Strangio, the work is about making clear how acts of discrimination against trans people are connected to a larger movement for equality. “What we need is a broader demand for justice and allied mobilization that connects trans survival to other movements for justice,” he says. —M.G.

Kimberly Teehee

A voice for Native Americans

In 1835, tucked away in a treaty ceding southeastern Georgia Cherokee land to the U.S., the government agreed that the Cherokee people “shall be entitled to a delegate in the House of Representatives.” Last August, the largest federally recognized tribe finally took Congress up on this offer by appointing Kimberly Teehee, 51, to be its first U.S. House delegate.

The position isn’t Teehee’s only policy-making first. As the first senior policy adviser for Native American affairs in the White House Domestic Policy Council, she spearheaded the provision in the 2013 Violence Against Women Act reauthorization that lets tribal courts prosecute non-Indians who commit certain domestic-violence crimes on Indian lands. Over half of American Indian/-Native Alaska women have experienced sexual violence. “Tribes, like other jurisdictions, should have the ability to prosecute crimes committed on their lands,” she says, “making sure American Indian women have the same protections that women have in this country.”

Teehee is still waiting to be seated in Congress, where, like the delegate from D.C., she would be non-voting. But the symbolism of her presence would be strong, she says, as “an extra voice in the room” for her tribe and all others. —Olivia B. Waxman

Alice Wong

Amplifying the disabled community

As the founder and director of the Disability Visibility Project, an online community that amplifies the voices of disabled people in culture, Alice Wong is familiar with the host of challenges currently facing disabled people, such as proposed rules by the Social Security Administration that would cut access to benefits, or a new “public charge” immigration rule that will exclude disabled people from staying in the country if they depend on public benefits.

Although the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act ushered in parking spots and elevators for disabled people, Wong, 45, says such efforts aren’t enough to protect the community. “There are constant attempts to decrease our rights, keep us separate and take away control of our narratives,” says Wong, who is currently putting together an anthology of first–person stories and essays from those in the disability community, set to come out this summer. “We need everyone to fight back with us.” —M.G.

This article is part of a special project about equality in America today. Read more about The March, TIME’s virtual reality re-creation of the 1963 March on Washington and sign up for TIME’s history newsletter for updates.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com