Jerry West saw something the other basketball mavens didn’t. Everyone around the league was intrigued by the slender high school senior with NBA genes and confidence to spare. But could Kobe Bryant really go directly from leading the Lower Merion High School Aces in suburban Philadelphia to guarding Michael Jordan? It took West, then executive vice president of the Los Angeles Lakers and one of the best players in NBA history, less than a half hour to know the answer. As part of a workout ahead of the 1996 draft, Bryant played one-on-one against the recently retired defensive specialist Michael Cooper. The GM ended the session early. “I was embarrassed for Michael to watch a 17-year-old just basically demolish him,” West tells TIME, “and enjoy doing it.”

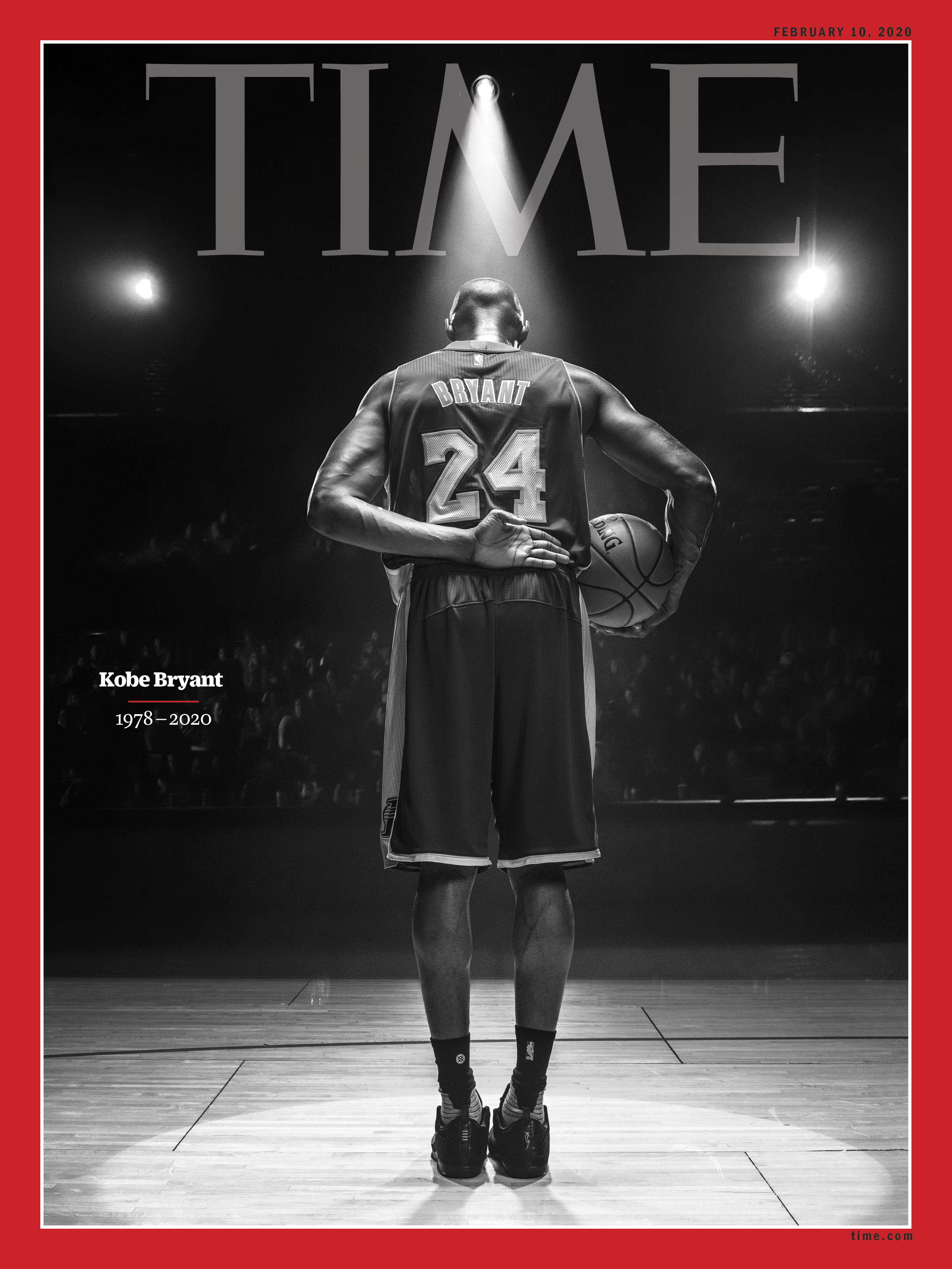

West acquired Bryant in a draft-day deal, pairing the teenager with the towering Shaquille O’Neal and launching one of the most decorated careers in professional sports. Over 20 seasons–all of them with the Lakers–Bryant won five NBA championships, two scoring titles, a pair of Olympic gold medals, one MVP award and was named to 18 All-Star teams. More than merely guarding Jordan, Bryant emerged as his heir, a scoring assassin who could rip a defender’s heart out by way of a devastating dunk or an elusive fadeaway jump shot from the baseline, his singular work of athletic art. His ascent coincided with the development of social media and basketball’s embrace around the world, which turned Bryant into one of the game’s first truly global stars. Back home, he inspired a generation of high school phenoms like LeBron James to follow his lead from high school to the NBA.

“You said Kobe, and everyone knows who that is: a one-word name,” says Quentin Richardson, who played against Bryant in the 2000s.

Driven by a focus and intensity that he would come to call–and trademark–Mamba Mentality, Bryant had the rare combination of elite talent and preternatural fire seen only in the true greats. “Kobe played the game,” says West, “like it was war.”

When Bryant retired in 2016, he had scored 33,643 points, good for fourth on the NBA all-time scoring list. He was in third until Jan. 25, when James passed him. Bryant called James and sent a congratulatory tweet.

The next day, Bryant was gone. The helicopter he was taking to his daughter’s youth-basketball tournament crashed in the hills near Calabasas, Calif. All nine people on board were killed, including Bryant’s 13-year-old daughter Gianna, known as Gigi, and two other young girls. Bryant had begun using helicopters as a player to avoid L.A. traffic on his commutes to home games, and to give him more time with his wife Vanessa and their children. The crash is still under investigation, though the National Transportation Safety Board said the helicopter was not equipped with a terrain-warning system that could have alerted the pilot to danger.

The loss was one of the most stunning in the history of sports and global celebrity that Bryant had done so much to fuse. To many, it was as if a vein had been opened. NBA players wept publicly. On Weibo, one of China’s largest social networks, the hashtag for Bryant’s death drew nearly 2.5 billion views in a day. Former President Barack Obama said, “Kobe was a legend on the court and just getting started in what would have been just as meaningful a second act,” and world leaders from Israel to Venezuela shared their own condolences. Murals of Bryant with his daughter appeared in states from Texas to Massachusetts. Across the Philippines, skyscrapers lit up in tribute.

In Los Angeles, thousands gathered to cry and light candles outside the downtown Staples Center–“the house that Kobe Bryant built” as host Alicia Keys called it at the top of a notably subdued Grammy Awards held in the arena that night. It has become a gathering place for Bryant’s legions of fans, who come bearing jerseys and balls much the way Buckingham Palace overflowed with flowers following the death of Princess Diana.

Reactions to Bryant’s death have deepened to reflect the dimensions and sometimes confounding complexity of his life. Though not cut down in the prime of his basketball career, Bryant, at 41, was well into a second act that gave him more prominence than many active players. He had already written an Oscar-winning animated short film, launched a production company, created a sports academy and become a vocal champion of women’s sports. “I absolutely believe he was going to do great things,” says Richardson, “and write another chapter of greatness after basketball.”

And he died being a parent. As word emerged that Gigi had been killed with him, queasiness was compounded by recognition. Every weekend, parents travel with their children to organized youth-sporting events, just like Bryant was doing with the second of his four daughters. Suddenly people who did not know Bryant, or particularly care for him, could picture themselves in his place, and choke up. To toggle between Instagram and Twitter in the days after Jan. 26 was to experience the social-media version of a wake: Gigi dangling from her father’s shoulders, or parked above them, her hands resting on his head. The two sitting courtside, exploring the nuances of the game.

Bryant’s biography included another critical element: in 2003, he was arrested and charged with sexual assault. The criminal case was dropped after Bryant’s accuser refused to testify in court. A civil suit ended with a settlement. Bryant issued a statement of apology, which read in part: “After months of reviewing discovery, listening to her attorney, and even her testimony in person, I now understand how she feels that she did not consent to this encounter.”

The case failed to derail Bryant’s career, and by the time he retired, it tended to be mentioned reluctantly, if at all, in assessments of his legacy. In the era before #MeToo, an NBA superstar could commute between games and court appearances without apparent consequence.

Bryant was the son of former NBA player Joe “Jellybean” Bryant and Pamela Bryant. He spent part of his childhood in Italy, where his father played professionally and where he learned both the language and a love of soccer. The family eventually settled outside Philadelphia, where Bryant grew into a phenom.

He was self-confident, and solitary, which disarmed teammates. At the 1998 All-Star Game in New York, Bryant, then 19, went right at Jordan in what was a clear generational shift. After Jordan retired from the Bulls, the Lakers of Shaq and Kobe won three straight NBA titles, from 2000 to 2002. Bryant and O’Neal had an inevitable falling-out: not even L.A.’s sprawl could contain those two alpha egos. When, in 2004, O’Neal was traded to Miami, many blamed Bryant, painted as a selfish ball hog and whose reputation was tainted by his criminal case.

Bryant chose to embrace the role of villain, creating the Mamba Mentality pop philosophy. It was an approach to life that required extreme focus, discipline and enthusiasm for taking on all comers. Magic Johnson’s perpetual smile didn’t fit Bryant’s style. Like Jordan, Bryant embraced brutal honesty and could be cruel to underperforming teammates.

The Lakers suffered some down years in the mid-aughts, but Bryant’s displays of individual excellence continued to make noise. In 2006, he scored 81 points in a game, the second highest point total in league history. Around that time Jerry Colangelo, the head of USA Basketball, told Bryant that if he wanted to play for his first Olympic team, he’d have to serve primarily as a passer, not a shooter. Bryant, though surprised, still promised Colangelo he’d do whatever was needed to bring a gold medal back to the U.S. Winning was always paramount. Colangelo was testing Bryant; the pair then shared a laugh, knowing that asking Bryant not to score was like asking a dog not to bark.

At an early training camp for those Beijing Olympics, Bryant arrived in the weight room before 6 a.m. Younger superstars like James and Dwyane Wade, according to Colangelo, learned to follow Bryant’s example. In China, where Bryant first hosted a clinic in 1998, hordes of people would greet the U.S. team bus. “They didn’t want to see us,” says Colangelo. “They wanted to see Kobe. They just kept chanting, ‘Kobe! Kobe! Kobe!'” The U.S. won gold in Beijing.

A Lakers renaissance followed. Los Angeles won back-to-back titles in 2009 and 2010, and Bryant was MVP of both finals. He continued to produce, but injuries plagued the last few years of his career. The 2015–2016 goodbye season served as both farewell and affirmation of his basketball greatness. In a full Mamba showing that was replayed on national television, in prime time, a day after his death, Bryant scored 60 points, on 50 shots, at the Staples Center in the final game of his career.

Rather than jump to TV or hawk products after his playing days, Bryant embraced the clean slate. He dedicated time to his venture-capital firm, created a musical podcast for children and won his Oscar for “Dear Basketball,” an animated film based on the poem he used to announce the end of his playing career. In addition to supporting women’s sports–Bryant was a regular presence at and cheerleader for the WNBA and U.S. women’s national soccer and gymnastics teams, among others–he became a devoted coach for his own daughters. He embraced the role, telling Jimmy Kimmel that his goal was to give the girls “a foundation of the amount of work and preparation that it takes to be excellent.”

“We lost a big advocate for women’s sports,” soccer icon Mia Hamm tells TIME. “But we’re all inspired by his belief in equality, and it’s our job to continue to move forward.”

She is among the many who believed Bryant’s best was ahead of him, which only added to the despair over his death. When athletes hang up their uniforms, they’re supposed to return to mortal life and age with the rest of us. They show up at ceremonies, hair a little more salty but the applause as raucous as ever. “I had a brother killed in Korea and honestly,” says West, “it affected me in the same way.”

The NBA’s silhouette logo is modeled after West in his playing days. A petition to change it to Bryant’s likeness has since received close to 3 million signatures.

–With reporting by Andrew R. Chow/New York

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Sean Gregory at sean.gregory@time.com