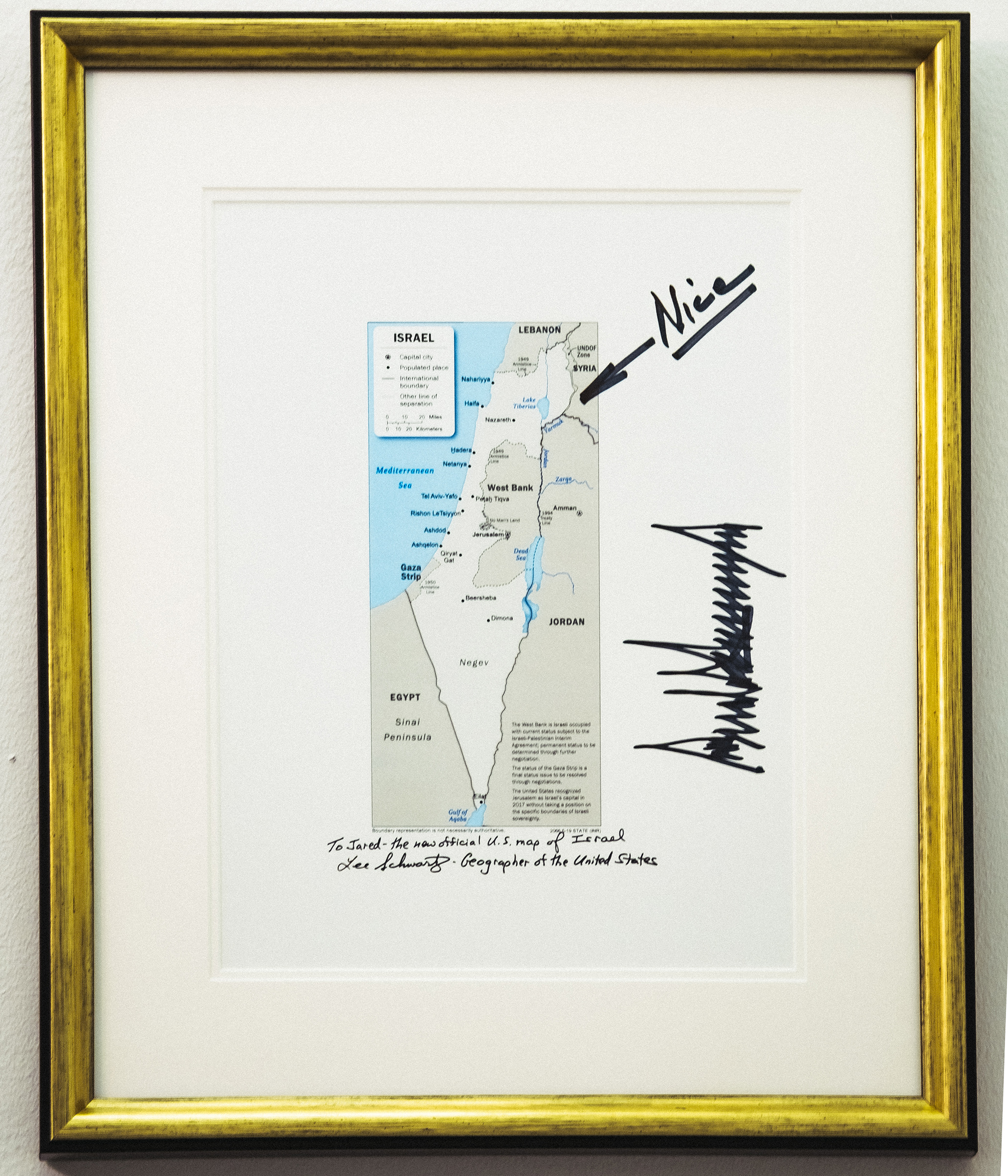

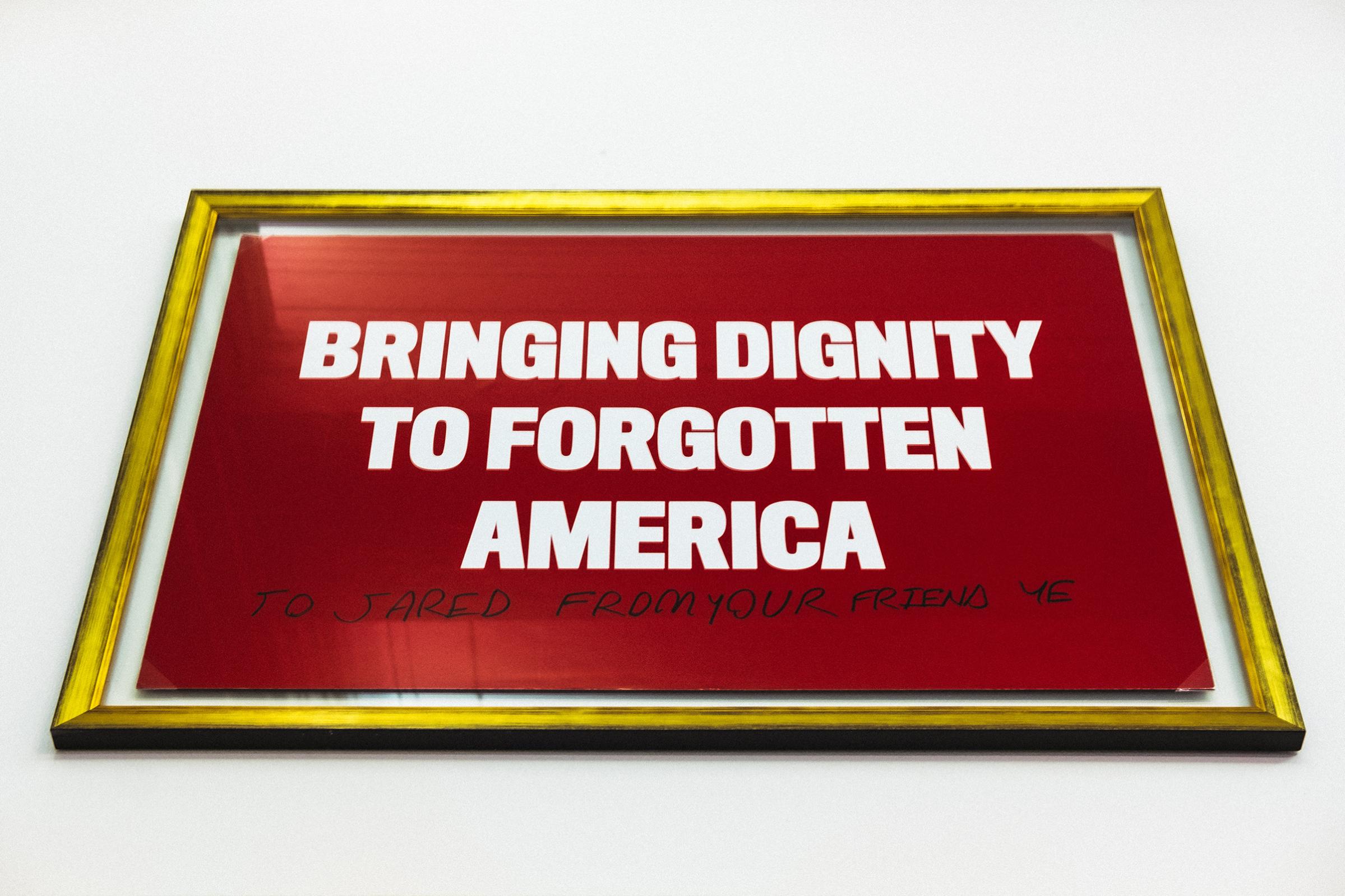

Jared Kushner’s White House office is a shrine to his own influence. Gold-framed accolades from his father-in-law hang on the walls, written in thick black Sharpie in President Donald Trump’s spiky hand. To Jared, Great job on Mexico. Thanks DAD, reads one. A limestone replica of the plaque marking the move of the U.S. embassy to Jerusalem, which Kushner helped orchestrate, rests atop a bookcase. There’s his medal representing the Order of the Aztec Eagle, the highest award given to foreigners by the Mexican government, with whom Kushner hammered out a trade deal. Above the door is a commemorative poster for the criminal-justice bill Kushner shepherded, signed by the rapper Kanye West. (To Jared from your friend Ye.) Near his desk sits a rack of folders with handwritten labels that nod to Kushner’s unrealistically broad policy portfolio: Health care, Lebanon, Border Infrastructure, Central America Econ Plan, POTUS Environment, DOJ [Department of Justice].

The office is smaller than the others lining the south wall of the West Wing, where some of the President’s top aides cloister. But Kushner, an erstwhile real estate developer, values setting over size, and chose the space adjoining Trump’s private dining room, the President’s favorite hideaway. “Not the biggest office in the world, but it’s a good location,” he explains to TIME. Kushner likes to show visitors the spot on one wall where a door to the President’s inner sanctum was plastered over. “This is where Monica used to come in,” he says, of the former White House intern who visited Bill Clinton’s study.

The rack of folders does not contain his entire portfolio. As senior adviser to the President, he’s been entrusted with brokering peace in the Middle East, building a border wall, reforming the criminal-justice system, pursuing diplomacy with China and Mexico, and creating an “Office of American Innovation” dedicated to revamping how the government works. Kushner is in charge of the President’s 2020 re-election campaign, overseeing fundraising, strategy and advertising. He has walk-in privileges in the Oval Office and can weigh in on any decision across the building. “Nobody has more influence in the White House than Jared. Nobody has more influence outside the White House than Jared,” says Brad Parscale, whom Kushner installed as Trump’s campaign manager. “He’s No. 2 after Trump.”

At the start of Trump’s term, very few people in Washington considered this a good thing. Some White House officials complained privately that the President’s decision to task his 39-year-old son-in-law with some of the world’s hardest problems made the Administration look incompetent at best and corrupt at worst. Conservative Republicans worried that Kushner and his wife Ivanka, both former Democratic donors like Trump himself, would steer the new President toward the political center. To liberals, Kushner was a case study in the dangers of nepotism, a dilettante playing diplomat who was either unable or unwilling to use his political capital to rein in Trump’s worst impulses.

His first few months after Trump won the White House were littered with mistakes that showcased naiveté. His meeting with a Russian banker linked to the Kremlin stoked speculation about collusion. His support for Trump’s decision to fire FBI Director James Comey helped trigger the appointment of special counsel Robert Mueller. His spotty top-security clearance application and ties his family’s real estate business has had to foreign governments forced the President to grant him a clearance by fiat, overruling counterintelligence officials and White House lawyers. Foreign intelligence services reportedly identified Kushner as a target for manipulation. As criticism rained down, Kushner was content to remain a cipher, often seen but rarely heard.

Kushner now acknowledges his learning curve. “I had some bumpy patches along the way. I got here, and obviously at the beginning, there’s a lot I needed to learn,” he tells TIME, sitting at a conference table in his office. “I didn’t know all the files that well. I didn’t know which files were my responsibility, which files were other people’s responsibility. I didn’t necessarily know what it took to be successful.”

But over the course of Trump’s term, few people have been as influential as Kushner. He was an architect of the primary bipartisan legislative achievement of Trump’s first term, the criminal-justice reform bill. He helped negotiate a revamped trade deal with Canada and Mexico. His push to tighten America’s embrace of Saudi Arabia and Israel has altered Middle East politics. He has proven a deft bureaucratic knife fighter, helping push out a series of senior staffers who tried to impose order on a freewheeling President. “Hopefully my results speak for themselves,” Kushner says. “I think that I’ve accomplished a lot. I think the President trusts me, and he knows I’ve had his back, and he knows that I’ve been able to execute for him on a lot of different objectives.”

The portrait that emerges from interviews with Kushner, current and former White House officials, lawmakers and people close to him is of an increasingly confident operator who is learning to pull the levers of power in the White House and throughout Washington in ways that may surprise critics. Listening to Kushner describe his role makes it clear that he was never going to be the moderating force that Democrats hoped for and Trump loyalists feared. He doesn’t see his job as steering Trump to a decision. He sees himself as the enabler of the President’s agenda.

“One thing you have to remember when you work for President Trump is that you don’t make the waves. He makes the waves,” Kushner explains in his office, a silver bowl of Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups on the table. “Your job is to surf the wave as best as you can every day. And you have to always smile and have a sense of humor with it, because he’s the one who’s got the instinct.”

The Trump presidency may depend on Kushner’s surfing skills. As the Senate prepares to convene its impeachment trial on Jan. 21, Kushner is overseeing strategy meetings in the West Wing to bring competing White House factions together and plot out the President’s defense. At the same time, he approves every expenditure of $1 million or more for the 2020 re-election bid.

America has a history of Presidents appointing family members to positions of power dating back to John Adams. John F. Kennedy’s closest adviser and Attorney General was his brother Bobby. Bill Clinton tapped his wife Hillary to run the signature issue of his first term, health care reform. But it is rare for a President to give such power to a family member with no policy experience. Kushner has proved he has the quality Trump prizes most–loyalty to the boss–but his blind devotion has sometimes carried a cost. Some White House aides argue that the President’s impeachment was the result of Kushner’s working to oust aides who had tried to put up guardrails to protect the President.

Kushner’s many critics inside the White House admit he is now nearly untouchable–one reason they all insisted on speaking anonymously for this article. And while he may have learned a lot in three years, when you’re tackling the world’s toughest problems, overconfidence can be dangerous. “He’s a classic ‘don’t know what you don’t know,'” says one senior Administration official. “He should stop assuming and ask some questions and try to learn.”

Sign up for the Inside TIME newsletter to get the exclusive story behind TIME covers.

On most mornings, Kushner wakes up around 5:30 a.m. in the $5.6 million white brick mansion he and his wife, Ivanka Trump, rent in Washington’s Kalorama neighborhood, where his neighbors include ambassadors, Amazon boss Jeff Bezos and the Obamas. He practices transcendental meditation–he won’t reveal his mantra–and puts an espresso pod into a coffee machine for his wife. On a recent morning when Ivanka was out of town, Kushner read the newspapers in bed with their youngest child while the eldest daughter walked the family’s fluffy white Pomsky, named Winter. (The duty conforms to a contract Kushner required the 8-year-old to write and sign before bringing the dog home.) By 7:15 a.m., Kushner is usually in the back seat of a black Secret Service SUV heading to the West Wing.

On Dec. 19, the day after Trump’s impeachment, Kushner had a full agenda at the White House. Over the course of three hours, Kushner worked on Trump’s effort to cut government regulations on businesses, expand school-choice programs and increase investment in poor urban neighborhoods. When Kushner’s team of nearly a dozen advisers packed his office, the updates ticked from immigration to technology upgrades at agencies to prison-release programs, along with a half-dozen other initiatives Kushner is tracking.

At one point, Kushner walked across the hall to the Roosevelt Room to offer advice to a group of White House fellows, young professionals spending a year working with senior staff and Cabinet secretaries. He salted his remarks with business jargon, using phrases like growth curve and calculated risk. “You’re always at a posture until you are at a deal,” he said.

It’s hard to pin down Kushner’s ideology. He did not register as a Republican until September 2018. White House officials were suspicious of his priorities and resentful of his clout. Turf wars were rampant. Kushner says he has learned to express his opinions with the President in private–usually in the White House residence or in the President’s dining room next door to his office–so that aides with competing interests don’t leak to the press. “It’s very rare that I’ll give my opinion to the President in front of other people,” he says. “I have my personal opinions and my personal sympathies, but I work for the President of the United States. And my job is to, when he asks my advice on things, give him my advice. But then when the President makes a decision, my job is to help him execute that decision.”

A descendent of Holocaust survivors, Kushner grew up in Livingston, N.J., in a family of Orthodox Jews. His parents were prominent Democratic donors close to Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who once crashed in Kushner’s childhood bedroom.

Kushner is no stranger to family controversy. When Jared was 23 years old, his father Charles pleaded guilty to illegal campaign contributions, tax evasion and witness tampering in a case that involved trying to influence witness testimony by setting up his brother-in-law with a prostitute and secretly videotaping the encounter. Kushner’s father spent 14 months in federal prison in Alabama. Kushner remains close with his immediate family, speaking with his parents on Friday nights before Shabbat. He wears a Kabbalah bracelet of red thread, a gift from his sister that invokes how his grandmother used to sew red thread into family clothing to ward off evil.

Kushner’s bond with Trump was forged by more than his 2009 marriage to the President’s elder daughter. Both men are ambitious scions who inherited real estate empires and lifted them to glitzier heights in Manhattan. Kushner’s cornerstone acquisition was 666 Fifth, which his company bought in 2007 for $1.8 billion. It was a record price paid at the wrong time: within a year, the recession hit and the debt became hard to service. Talks between the Kushner Companies and business interests in China and Qatar in 2017 sparked speculation by Democrats that those countries might be trying to gain leverage over Kushner.

Like the Kushners, Trump prefers to run his enterprises as a family business. So when he launched his campaign in 2015, Kushner was eventually drawn into the fold, and he quickly became a key adviser, pushing a blitz of Facebook ad buys and encouraging Trump to do more friendly interviews with local television stations in swing states. Trump leaned on Kushner, who took no title in the campaign, to oversee decisions about spending, advertising and travel.

Campaign officials competing for power often waited until Friday nights to approach Trump about decisions Kushner opposed, according to two former campaign officials, knowing that as modern Orthodox Jews, Kushner and Ivanka would be home for Shabbat and off electronic devices. In October 2016, rivals tried to strip Parscale’s control over television ad buys while Kushner was out of the office observing Yom Kippur.

But Kushner proved a capable infighter as well. During the presidential transition, he persuaded Trump to jettison former New Jersey governor Chris Christie, who had once prosecuted Charles Kushner. (Kushner has publicly denied doing so.) He nixed a host of conservatives who had criticized Trump for key Administration posts. And he worked to sideline officials whose objectives he believes were different from the President’s. “The biggest source of tension I had early on with different people here centered around the fact that people wanted him to make decisions that they want him to make, as opposed to getting him information,” Kushner says. “He’s rotated out a lot of the people who have maybe been more in it for themselves than for him.”

But bringing on board malleable underlings has sometimes produced the unique chaos of Trump unbound, and Kushner’s own feel for people has been spotty. He pushed for Michael Flynn to be hired as National Security Adviser, a job that lasted 24 days after Flynn became embroiled in an FBI investigation over his lying about a phone call with the Russian ambassador. Later he helped push out press secretary Sean Spicer to bring in New York financier Anthony Scaramucci, who imploded within 10 days. His decision to embrace Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman backfired when Saudi agents killed Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Istanbul.

There were policy flaps too. Flouting Republican doctrine, Kushner consulted former Obama Administration health adviser Zeke Emanuel about salvaging the Affordable Care Act, according to one current and one former White House official. Kushner held talks with Republican Senator Lindsey Graham about rewriting U.S. immigration laws behind the back of then Department of Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly, according to the officials. Carping about Kushner became an unofficial pastime in the Trump Administration.

Six months into his term, Trump tapped Kelly, a retired four-star Marine general, as chief of staff to impose a dose of military discipline in the building. Kelly tried to curtail Kushner and Ivanka’s influence, insisting they schedule appointments through him to see the President. For a time, Kushner’s power in the building seemed to wane.

But as Kushner knew, nobody who tries to control Trump lasts very long. One by one, his antagonists fell by the wayside, and Kushner was there to fill the void.

In late 2017, Kushner was at loggerheads with then Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and then Defense Secretary James Mattis over moving the U.S. embassy in Israel to Jerusalem, a campaign promise. Tillerson and Mattis warned the move would ignite a conflagration in the region, endangering American lives. Trump overrode them and sided with Kushner. “I just want to say for the record, I am against this,” Tillerson told Trump during a secure meeting in the White House in November 2017, according to a White House official.

Less than a month later, Tillerson learned he was being fired as he read Twitter on the toilet. Kushner and others suggested replacing him with CIA chief Mike Pompeo, a former Kansas Congressman with whom Kushner had gotten along during the presidential transition. Pompeo took the job and has become one of Trump’s most loyal aides, pushing a pro-Israel, anti-Iran agenda that comports with Kushner’s.

When the drive to replace the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), another Trump campaign promise, stalled in the spring of 2018, Kushner flew to Mexico City to meet with Luis Videgaray, then the Mexican Foreign Minister. Kushner persuaded Videgaray to peel away from Canada in the negotiations and deal directly with Trump, giving the President an edge on concessions from both countries.

The move infuriated some White House officials, who resent the way that they say Kushner steps in to take credit for projects they’ve been working on for months. “Sometimes he comes in, he f-cks everything up, and if it works well, he takes credit, [but] if it’s sh-tty, he just flits away,” says another senior White House official, who like others spoke on condition of anonymity, noting that Kushner’s influence with the President makes public criticism dangerous.

U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer offers a different view. In the final push for the trade deal known as the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), Kushner “was in my office sitting in those negotiation sessions for weeks and weeks, and we would go to 10, 11 at night,” Lighthizer recalls. “He’s tough and he’s 100% with the President.”

Kushner’s sway now extends to Congress, where he helped drive the First Step Act, a modest package of prison reforms, into law. Powerful Republicans, including Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell, were skeptical. In November 2018, Trump summoned Kushner to the Oval Office for a meeting. “Mitch, why don’t you tell Jared what you told me,” Trump said. McConnell told Kushner there weren’t enough days on the calendar to move the legislation. Then he turned to Trump and joked that Kushner had been having everyone in his Rolodex lobby McConnell. “I have a lot more people lined up to call you,” Kushner said. Trump laughed and told the pair to work it out. Kushner’s pressure helped persuade McConnell to put the bill on the floor, where it passed in December 2018.

Kushner’s work on criminal-justice reform helped persuade some skeptics in the White House that his value had begun to outstrip his inexperience. “If you want to measure a cost-benefit analysis,” says a former White House official, “that’s a clear example, and I think there are others like it, where the value-add significantly exceeds whatever kind of drawbacks might exist.”

Kushner’s role in the White House is different from that of his wife or her siblings. While Trump’s sons stayed in New York to run the family real estate business, Ivanka Trump has taken on a small but well-defined portfolio of popular issues–workforce development, women’s empowerment and paid family leave–while steering clear of more controversial subjects. Kushner, on the other hand, has taken on radioactive projects like the border wall.

“The President tends to task Jared with his highest-priority projects,” Ivanka Trump tells TIME. “He obviously has a very well-defined and large portfolio, but the President will often call on him to handle other issues that are of significance.”

On a drizzly Tuesday in January, Kushner climbed into a black Chevy Suburban heading to Washington’s Reagan airport for a flight to Milwaukee. He was due to attend a Trump rally and a meeting on criminal-justice reform. In the car, he spoke by phone with Secretary of Defense Mark Esper to get an update on border-wall construction. Secret Service agents whisked him through security and onto a Southwest Airlines plane. During boarding, several passengers looked wide-eyed at Kushner as he walked past, but none said anything to him. Kushner took a phone call from a senior Mexican official and kept talking as the plane taxied and lifted off. The two spoke until the call dropped off as the plane gained altitude.

In northwest Milwaukee, Kushner sat at a long table at the Greater Praise Church of God in Christ and listened to stories from former inmates who had found jobs through a local faith-based program called the Joseph Project. Some of them had been released early under provisions in the First Step Act. One person at the event said Kushner’s experience visiting his father in federal prison had clearly given him a better understanding of the challenges people face after being incarcerated. Kushner nodded. “It didn’t come at a cheap price,” he responded.

Kushner believes that prison reform could improve Trump’s paltry support in African-American communities. He’s most focused on neighborhoods like this one, which happen to be in crucial swing states. One of the core themes Kushner is hammering for Trump’s re-election campaign is that the President has fulfilled his promises. There are, of course, big exceptions–like the border wall. But Kushner knows that in a tight race, expanding the President’s coalition even a little bit beyond his core supporters could prove critical. “You think about prison reform. He didn’t even promise to do that. He came in and he got that done,” Kushner says as his car wheels away from the low-rise brick sanctuary. “He’s delivered for his voters, but he’s also delivered for people who were not his voters.”

He says the key states in 2020 will be Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania. He says data has persuaded him to push the campaign to compete in states like Minnesota, New Mexico, Nevada and Colorado as well. If Trump wins a second term, there’s a fear among conservatives that Kushner’s influence will only grow. And it seems increasingly clear that Kushner and his wife aren’t going anywhere. “I think there’s a lot more that we can do,” Kushner says. “Hopefully, I’ll get the chance through a second term to continue to put these reforms into place.”

Left unmentioned is the question of whether Kushner, a fixture in Manhattan business and media circles, would be welcomed home after working on behalf of a President many of his old friends and associates detest. “I’ll be honest. My family likes Washington,” he says. “The kids love their schools. The lifestyle here is quite nice. But for me, I like challenges. I think the challenges I get to work on here are some of the most complicated, best challenges you could find.”

As the sunlight fades in Milwaukee, Kushner’s SUV glided past a snaking line of hundreds of Trump supporters waiting to get into the UW-Milwaukee Panther Arena for Trump’s rally. The car stopped by the stadium’s loading docks and Kushner jumped out. Walking inside, he spotted Parscale, who was waiting to give Kushner an update on the Wisconsin campaign operation. A Phil Collins song thumped from the speakers. “I’ve got a meeting with the campaign team now,” Kushner said. “And then wait for the President to get here, and have some fun when he does.”

–With reporting by TESSA BERENSON/WASHINGTON

Correction, Jan. 22

The original version of this story misstated Charles Kushner’s guilty plea. He pleaded guilty to setting up his brother-in-law with a prostitute, not his brother.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com