The man’s scraggly hair and white bushy beard hung from a wrinkled face as he stood with a shopping cart filled with clothes, shoes and empty cans. When Americans spot such a homeless person, the impulse is often to hurry past. That’s impossible when you suddenly realize that the homeless person is your old friend and neighbor.

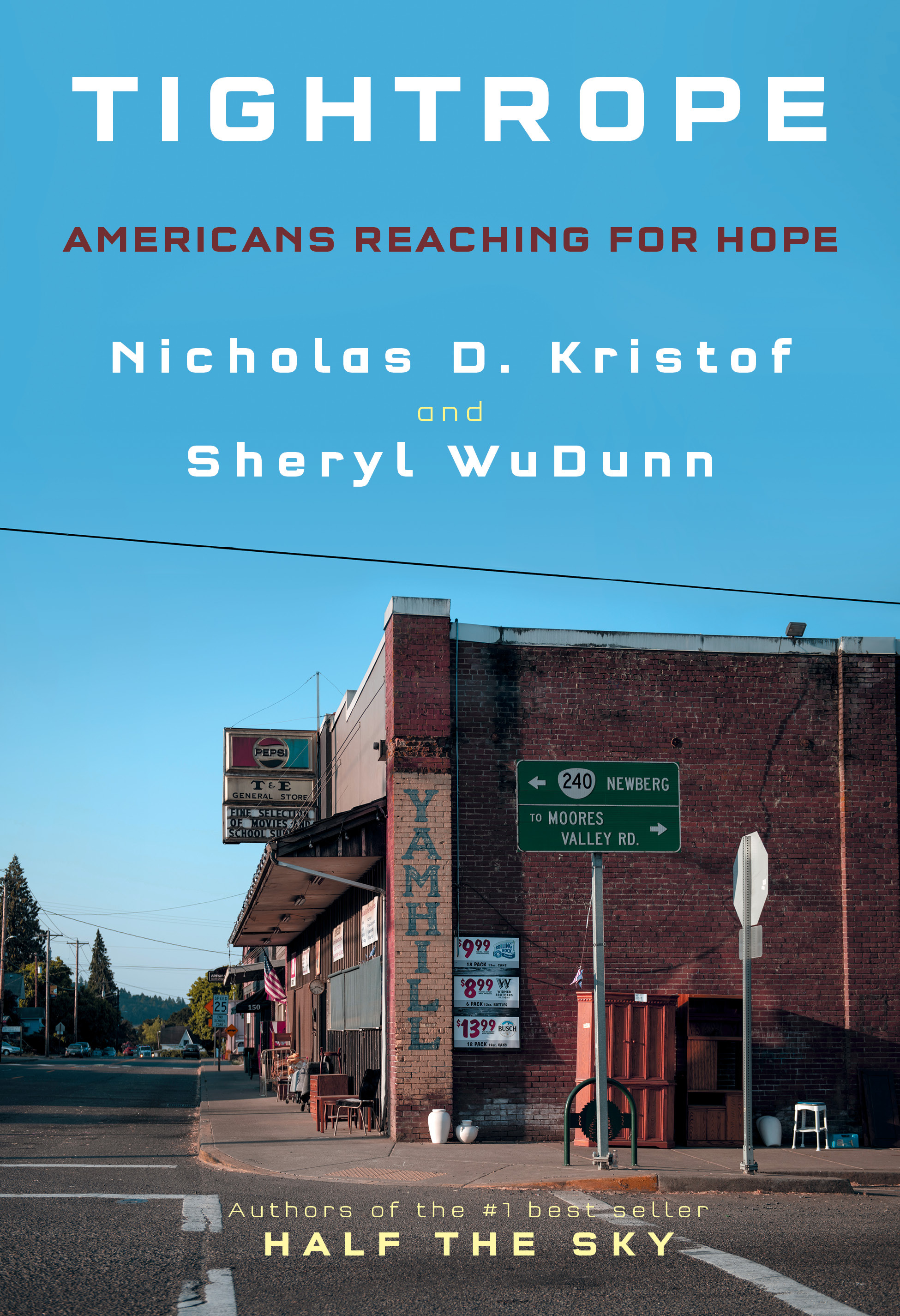

“It’s good to see you,” Mike Stepp greeted us warmly. Mike and his brother, Bobby, were Nick’s closest neighbors growing up, and they used to walk together to and from their school bus each day in rural Yamhill, Ore.

Their family had purchased a home and seemed to be living the American Dream. That was true across America: until the 1970s, the working class made enormous gains. Yet Mike and Bobby both dropped out of high school and struggled to find good blue collar jobs like the one held by their dad, a Korean War hero who worked in a lumber mill. Mike self-medicated with alcohol and drugs. As for Bobby, he’s serving a life sentence in prison for child sexual abuse.

They are lucky to be alive. About a quarter of the kids who rode Nick’s bus are dead from drugs, alcohol, suicide, reckless accidents or similar pathologies. Two separate families have lost four of five children.

This wasn’t one town’s problem but a crisis for all of working-class America, whether white, black or brown. “Deaths of despair,” as mortality from drugs, alcohol and suicides is known, have sent life expectancy in the U.S. falling for three years in a row, for the first time in a century.

In affluent America, people either don’t notice this humanitarian crisis or think that it’s hopeless. But there are tested solutions that are imperfect but do chip away at these problems–and often save public money.

The highest-return investment available in America today isn’t in hedge funds or private equity, but in at-risk children. It’s much easier to help a 3-month-old or a 3-year-old than a 13-year-old or a 30-year-old. Programs like Nurse-Family Partnership or Reach Out and Read help young children as their brains are developing. The results are outstanding.

Another crucial public investment is in drug and alcohol treatment. America’s big policy response to narcotics was the war on drugs, which was expensive and ineffective. It should be a scandal that just slightly more than 1 in 10 Americans with substance-abuse disorders gets treatment. Every dollar invested in treatment can save about $12 in reduced crime, court costs and health care savings.

We also can do much more to help people find well-paying jobs. If the federal minimum wage had kept pace with inflation and productivity since 1968, it would now be more than $22 an hour, not $7.25. That’s one reason 76% of adults expect their children’s lives to be worse than their own–and one reason so many white working-class men and women voted for Donald Trump; he did particularly well in areas with high rates of “deaths of despair.”

Most other countries have figured out how to tackle these problems. Automation and globalization affect workers in Canada and Germany as well, but life expectancy is not falling in those countries. Meanwhile, the U.S. has effectively addressed some social problems. We’ve reduced teen pregnancy. We’ve raised high school graduation rates. We’ve cut veteran homelessness–which suggests that if we wanted to slash child homelessness, we could probably accomplish that too. So there’s reason to be optimistic.

Something similar to today’s malaise occurred in the Soviet Union. It was still a superpower in the 1980s, but its achievements rested on a cracking economic and social foundation. Alcoholism was rife and life expectancy was falling, but officials didn’t expect the problems to reach the Kremlin. Their solution was to stop publishing Soviet mortality data.

We in America today face a similar choice. Do we face up to this crisis and try to address it? Or do we avert our eyes? Dr. Ben Carson, the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, has argued that poverty is “really more of a choice than anything else.” It’s true that some people engage in self-destructive behavior, but we as a country are doing the very same thing. If poverty and suffering are a choice, let’s face the fact that this is America’s choice, and that we can make a better one.

Adapted from Tightrope: Americans Reaching for Hope. Kristof, a New York Times columnist, and WuDunn, a business consultant, were the first married couple to win a Pulitzer Prize for journalism

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com