“Ever since The Simpsons came out, adult animation has basically been an arms race of different ways to copy The Simpsons,” says the writer and animator Alex Hirsch.

It’s not hard to see the ubiquitous influence of that iconic series, which premiered 30 years ago this week, across the last three decades of American adult animation. Family Guy, King of the Hill, Bob’s Burgers and many others have all featured some variation of the slovenly dad, the beleaguered wife, the rabble-rousing roost of kids and an animal who dig themselves into and out of minor crises each 22-minute episode. Non-family-based shows, from Robot Chicken to Archer, have also drawn heavily from Matt Groening’s hyper-referential style, irreverence and slapstick humor, with South Park dedicating an entire episode to the impact and dominance of its yellow predecessors.

But while The Simpsons may still be the North Star of adult animation, it’s not the only blueprint anymore. Over the past five years, a generation of shows challenging norms in content, tone and form has exploded onto TV and streaming platforms. These shows—including Netflix’s BoJack Horseman and Big Mouth, Adult Swim’s Rick and Morty and Amazon’s Undone—explore depression and mental health in profound ways, feature characters that age and mature from season to season and sometimes don’t even aim for laughs at all.

And many in the industry say that this boom is just beginning. The globalization of content has opened up American audiences to high-quality adult animation shows from Japan, France and elsewhere, raising the bar for everyone. As the streaming wars escalate, Netflix, Hulu and others are investing millions of dollars in animation studios and creators, leading high-profile names like Kenya Barris, John Mulaney and Patton Oswalt to bring their talents to the cartoon world.

Meanwhile, a new crop of diverse creators that grew up on the The Simpsons is seizing these opportunities to push the boundaries of a form has often been perceived as crude or juvenile. Collectively, they are transforming a once narrowly-etched genre into one of the most elastic and vital art forms of the 21st century. Hirsch, the creator of the Disney Channel’s critically adored Gravity Falls who signed an overall deal with Netflix last year, adds, “Now that animated content has been freed from the need of appealing to everyone, I think we’re going to see a fast evolution that’s been long overdue.”

“It felt like a radical idea that adults would watch cartoons”

Animation has a central part of American culture ever since Felix the Cat debuted in 1919. But cartoons specifically for adults as opposed to children are a relatively new development, coming to mainstream prominence only after The Simpsons’ success in the early ‘90s. Fox, in particular, dove in head-first with sitcoms like King of the Hill (1997) and Family Guy (1999); these snarky and potty-mouthed shows generated massive audiences and soon defined the genre’s mainstream confines. “In the past, if you weren’t right for Fox Sunday night, then you weren’t on the air,” Nick Kroll, the co-creator of Big Mouth, tells TIME.

In 2000, the creative team at Cartoon Network decided to carve out a new programming block after noticing how many adults were tuning in to their channel. “Every day we would look at our ratings and see that even at three in the afternoon, a third of our audience was adults watching Scooby Doo—and they’re not even parents,” Michael Ouweleen, the president of Cartoon Network and Adult Swim, tells TIME.

But when he, Mike Lazzo and their colleagues pitched the idea that would become Adult Swim, a confused executive suggested they run old episodes of Bonanza and Gunsmoke instead. “It felt like a radical idea at the time that adults would watch cartoons,” Ouweleen says. Eventually, they were given a short leash to create a new set of shows that included Aqua Teen Hunger Force and Harvey Birdman, Attorney at Law. Made on the cheap and primarily aimed at young men watching in middle of the night, Adult Swim’s burgeoning slate leaned into transgressive and often shocking images and content matter—and soon developed a cult following.

For years, a creative dichotomy cleaved adult animation in two: between low-budget late-night experimentation and often staid, universal sitcoms. But the streaming economy started to collapse this tension. Netflix got in on the game after executives there watched shows like Bob’s Burgers and American Dad rack up huge numbers in the platform’s early days. “Knowing how well licensed content did—and knowing they might not always be on our service—there was a huge appetite for it,” Jane Wiseman, Netflix’s vice president of original comedy series, tells TIME.

Meanwhile, a culture of nostalgia on the big screen was developing, in which reboots of family-oriented fare were being released and devoured at an accelerating rate—from Star Wars to Spider-Man to Toy Story sequels. Adult audiences seemed to find comfort in the familiar; Comic-Con became a multi-city blockbuster event. Previous taboos that might have discouraged adults from enjoying children’s entertainment were quickly receding.

So at Netflix in 2014, Wiseman started work on a trio of animated shows: BoJack Horseman, F is For Family and Disenchantment. At first glance, all three hewed close to the genre’s long-lasting mainstream conventions. F is For Family followed an archetypal Simpsons-esque family, with Bill Burr voicing the idiotic father. BoJack Horseman reveled in the contrast between its cartoonish visuals and its protagonist’s reckless behavior, while the fantasy spoof Disenchantment was created by Groening himself.

“Not something I would have done on network”

But each show quickly began to diverge from the norm. While Homer’s constantly changing job title is a gag on The Simpsons, Frank’s firing from the airport in F is For Family leads to a downward spiral and an existential crisis. BoJack’s foibles as a horse struggling with alcoholism are initially played for laughs, but his arc turns increasingly bleak as he causes devastating harm to the people (and anthropomorphic animals) around him. The ends of episodes don’t act as reset buttons: the depravity and depression of BoJack and Frank only mount as the shows stretch on, and they far more resemble the antiheroes in live-action drama than the bumbling-yet-harmless sitcom dads of yore.

“At first, we had to couch some of the sadder or weirder or more introspective stuff within the costume of a typical adult animated comedy,” Raphael Bob-Waksberg, the creator of BoJack, tells TIME. “But an intention of mine while making the show was to push the edges of what an adult animated show can be.”

Netflix, for its part, embraced these tonal shifts as part of a strategy to give uninhibited creative freedom to showrunners. Whereas network shows had to appeal to as wide an audience as possible, Netflix aimed to gain the allegiance of many smaller but more fervent fanbases. “BoJack was maybe not something I would have done on network—but it was a big swing with some really personal and universal truths to it,” Wiseman, who previously worked at NBC and Fox, says.

Netflix took another risk in 2017 on Big Mouth, a show about puberty co-created by the veteran comedian Nick Kroll. Kroll had previously worked in many different mediums—including theater and sketch comedy—and his decision to pivot to animation originated in practicality. “Historically, shows about kids coming of age around puberty, those kids mature. You only have a few years of Fred Savage before he became a teen,” Nick Kroll says of the Wonder Years star.

But the medium’s creative advantages quickly became evident. “Once we realized we could use hormone monsters and different kinds of creatures to personify the emotional states that these kids are going through, animation just felt like the perfect solution in so many ways,” Kroll says. Animation allowed them to offer both escapism—complete with sex pillows, bath mats and the ghost of Duke Ellington—and a lighthearted guise that could be used to smuggle in heavier ideas about anxiety, depression and sexuality.

And Kroll and his team were emboldened not just by the visual medium, but the leeway that being on a streaming service afforded them. Big Mouth didn’t have to adhere to strict 22-minute episode formats with generic ad breaks; they could stretch and squeeze plotlines, create impromptu musicals, and make riskier jokes aimed at big targets. “They don’t have advertisers who people can complain to about material, or scare us to make us revise things,” Kroll says. “We can talk about corporations and things and we won’t get in trouble for it.”

“Oh my god, we need to keep doing a lot of animation”

The first season of Big Mouth was released in September 2017 to huge global numbers, according to Netflix. (The company is selective about the data it releases and has not released official numbers for this series.) “Big Mouth was a true game-changer for us,” Wiseman said. “I was like, ‘Oh my god, we need to keep doing a lot of animation. People love it.’”

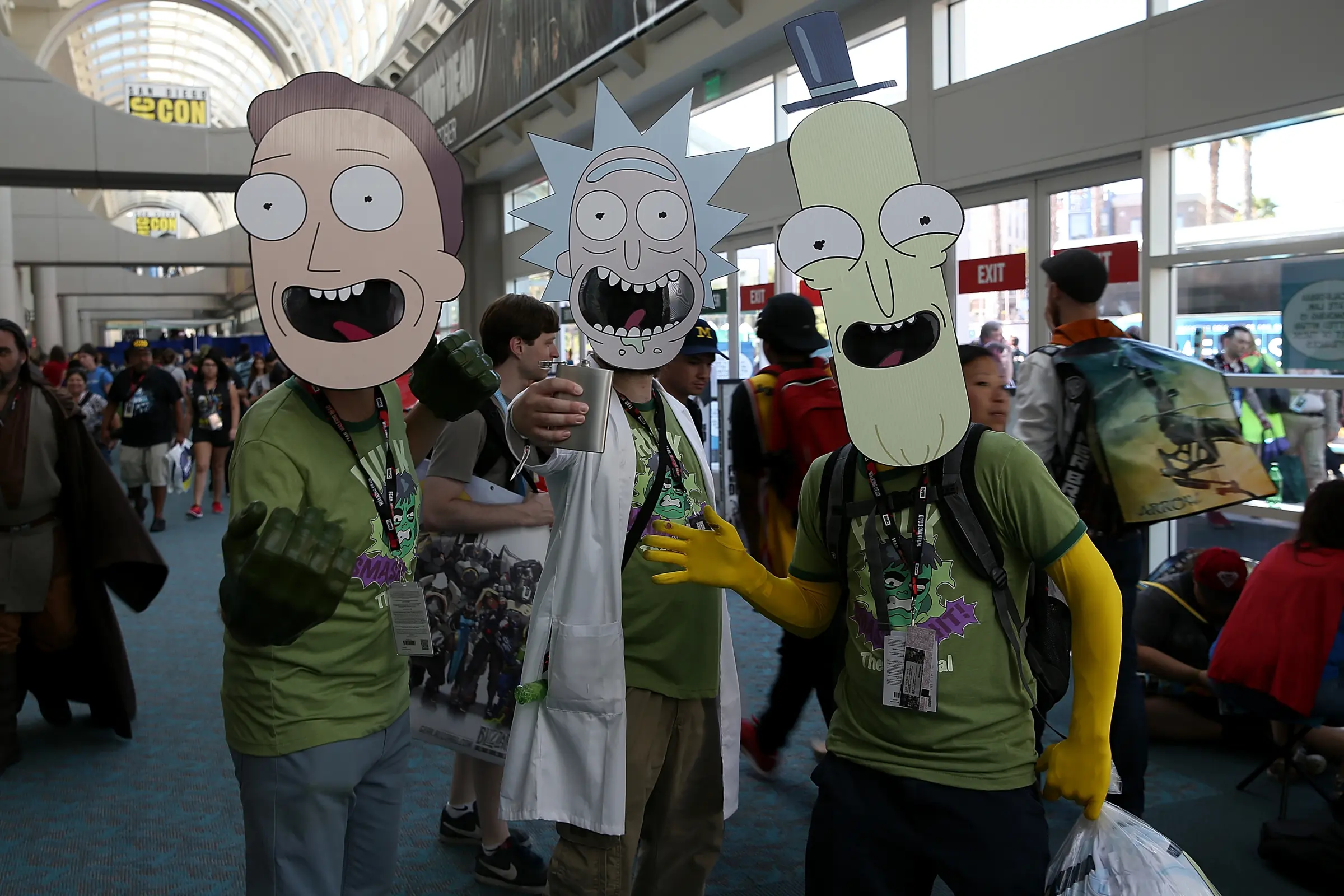

In the same month as Big Mouth’s release, BoJack Horseman’s fourth season received rave reviews for its depiction of dementia, while McDonald’s brought back Szechuan Sauce thanks to a plot point on Adult Swim’s Rick and Morty. Suddenly, a depressed horse, an alcoholic mad scientist and two preteens with talking pubes had zoomed to the center of pop culture.

Wiseman recognized the floodgates were opening, and quickly hired the animation veteran Mike Moon (who previously worked at Sony and Disney) to lead an entirely new adult animation division at Netflix. With little oversight and plenty of cash, Moon would order a slew of new series in the next year including HOOPS and Q-Force, positioning Netflix as the leader of a flourishing genre. Their most recent ambitious endeavor, The Midnight Gospel, is led by Pendleton Ward—creator of the revered animated series Adventure Time—and comic Duncan Trussell. The show, which arrives in 2020, forges intergalactic interviews based on clips from the freewheeling Duncan Trussell Family Hour podcast.

“We are really exploring the edges of what an adult animated show means,” Moon tells TIME. “What you’re going to see now is a real acceleration in tone and in types of stories.”

But with the streaming wars in full swing, Netflix’s competitors weren’t far behind. Apple nabbed a show from Bob’s Burgers creator Loren Bouchard. CBS launched a production arm, CBS Eye Animation, to develop shows, while HBO Max ordered a reboot of The Boondocks, its acerbic ‘00s comedy centering on a black family living in a mostly-white suburb.

Hulu, too, got aggressive after seeing how well its own licensed content like Family Guy and Rick and Morty performed. According to a representative, a third of their subscribers watch at least one animation title a month. So last year, they ordered a new show from Rick and Morty creator Justin Roiland, entitled Solar Opposites; in February, they signed up for a four-series slate of Marvel stories, with a set of creators that includes the comic Patton Oswalt. “Hulu viewers love adult animation,” Craig Erwich, Hulu’s senior vice president and head of originals, told TIME. “Given the circulation and the hunger, it’s a very fertile ground to launch originals.”

“Serious Stakes”

In 2018, the global animation industry was worth $259 billion—and according to the data provider Research and Markets, it’s projected to reach $270 billion by 2020. And as the adult animation field grows, it has continued to diversify in myriad ways. “You can only watch the same show with the same perspective so many times before you get bored out of your mind,” Hirsch says.

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, the first animated feature film in the Spider-Man franchise, used a groundbreaking comic-book-derived visual style to bring to life a black-Latino Spider-Man. Primal, on Adult Swim, received critical acclaim for its unconventional narrative approach that completely lacked dialogue. Kenya Barris (black-ish) and the rapper Kid Cudi will team up to create Entergalactic, a musical-visual adaptation of Cudi’s upcoming album, on Netflix.

And Amazon’s Undone uses rotoscoping—a visual technique in which animation is layered over live-action footage—to explore the mental health battles of a young Latina woman, voiced by Rosa Salazar, who may be suffering from schizophrenia. “We’re not keeping a comedic arms-length by having talking animals, or making it absurdist at the top,” says co-creator Kate Purdy, who was also a producer and writer on BoJack Horseman and who created Undone with Bob-Waksburg. “These are very real people who have very real relationships with serious stakes.”

Undone represents how far the genre has come. Although the show is undeniably funny, it’s much more a drama than a comedy. Its dialogue is opaque and naturalistic rather than based on punchlines; its disorienting kaleidoscopic visuals are light-years ahead of The Simpsons’ blobby doodling, and they capture mental imbalance in a way that live action never could. And its protagonist, Alma, joins Daria and another newcomer, Jenny on Fox’s Bless the Harts, as one of the very few female protagonists in American adult animation history (Hirsch says you can count them on “half a hand”).

Oweleen says that female viewers have started flocking to the medium, watching anime on Adult Swim with the same frequency as male viewers. And another female lead will soon join Alma: the currently unnamed protagonist of Inside Job, an upcoming Netflix show created by Shion Takeuchi with Hirsch serving as an executive producer. Takeuchi, who wrote for Disenchantment but has never led a show before, was the first female animator to be given an overall deal by Netflix. Takeuchi hopes that the show, about a woman embroiled in government conspiracies, will push the boundaries of the form even further: “Traditionally, adult animation spends a lot of budget on stuff like voice talent at the expense of the look and design,” she says. “But our show looks fantastic. And there is an emotional component to this story that I think 10 years ago would have been unheard of.”

Being given opportunities isn’t the same thing as lasting success or parity. Lisa Hanawalt’s Tuca and Bertie, which starred two women of color and garnered strong reviews, was canceled after one season. Marvel’s Tigra & Dazzler—the only show in the Hulu-Marvel slate to both be led by female writers and focus on female characters—was thrown into turmoil this month after showrunner Erica Rivinoja and writing staffers departed amid creative differences, according to Variety.

A 2019 report by the USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative concluded that the percentage of female producers in animation has improved over the past decade—but still, women made up just 17% of the creators and topline developers of the top 100 animated series in 2018. “I’m seeing people of color and women at the helm of things around me at the offices at Netflix—but as an industry, we still can do better,” Takeuchi says.

While the fight for representation will no doubt continue over the next decade, so will the battle for adult animation as a whole to be taken seriously—and thanks to a changed media landscape, animators finally feel they have the wind at their backs on both counts. “The phrase ‘adult animation’ conjures an image in most peoples’ minds of a character aggressively swearing with bright colors,” Hirsch says. “But adult doesn’t have to mean crass and cruel—it can mean sophisticated, dramatic, beautiful and nuanced.”

Correction, Dec. 20

The original version of this story misstated the nature of Shion Takeuchi’s hiring at Neflix. She was the first female animator to sign an overall deal with Netflix, not the first female creator overall to sign one. The original version of this story also misstated Mike Moon’s involvement with ordering the shows Tuca and Bertie and Paradise PD at Netflix. The shows had been ordered before Moon’s arrival–he did not order the shows.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com