Samuel Holmes Doten of Plymouth, Mass., was born June 5, 1812, so after the Civil War ended in 1865, he would joke that he “served in the infantry in the war of that date.”

William Kendall Crossfield, a Peterborough, N.H. native, was having a rest during the battle of Fredericksburg when he was shot in the neck while turning over. The blanket he had pulled up to his chin miraculously cushioned the bullet, but he passed out from the shock of the blow.

Vermonter Almeron C. Inman was recommended for the Medal of Honor of Feb. 9, 1887, “for intelligent coolness and bravery” in two 1864 engagements. After going missing for three months in 1895, he was found dead, thought to have killed himself.

The three men had different Civil War stories, but they also had something in common: like many who fought during that conflict, they were photographed in uniform. Multiple copies of the photos were made, and some became untethered from identifying information. Their faces became nameless symbols rather than part of concrete lives. And few of those pictures ended up with David Morin in Exeter, N.H., who boasts a collection of more than 260 Civil War military pictures.

Until now, these three men remained a mystery to him — but in the course of the last year, he identified them using Civil War Photo Sleuth, a website that uses facial recognition technology, a form of artificial intelligence (A.I.), to identify the men in such photos. And in 2020 the site is planning to add a new feature, after a successful test: a way for users to get second opinions on potential photo matches.

“Today history is so much better documented and the chances of things living on are so much greater,” says Morin.

While the Civil War started 158 years ago, the market for Civil War photography collections is relatively new, according to Ron Coddington, one of the site’s collaborators and the publisher and editor of Military Images magazine. There are photos of prior American military conflicts, but the Civil War is considered the first systematically photographed war, ushering in a new era of photojournalism in America. But by the time the centennial of the beginning of the Civil War arrived in 1961, bringing a new wave of interest in the conflict among history buffs, albums from that period were increasingly held by collectors rather than private families. In that transition, much information about the images had been lost. Though books about Civil War photographs, with basic biographical information, started coming out in the ’80s, many collectors had no easy way of learning the names of the people in the pictures they owned.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

The founder of Civil War Photo Sleuth, Kurt Luther, a professor of History and Computer Science at Virginia Tech, got interested in Civil War photography in 2013 after he stumbled across a photo album containing an image of his great-great-great uncle, who served in Company E of the 134th Pennsylvania, in an exhibit on Pennsylvania’s role in the Civil War at the Senator John Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh. As he started to learn more about such pictures, he began to imagine a Wikipedia for Civil War photos — a resource anyone could add to, which would help figure out who the men in the pictures were.

“Collections often don’t know what they have,” he says. “They have Civil War photos, and they don’t even know how they got them.”

The result was Civil War Photo Sleuth.

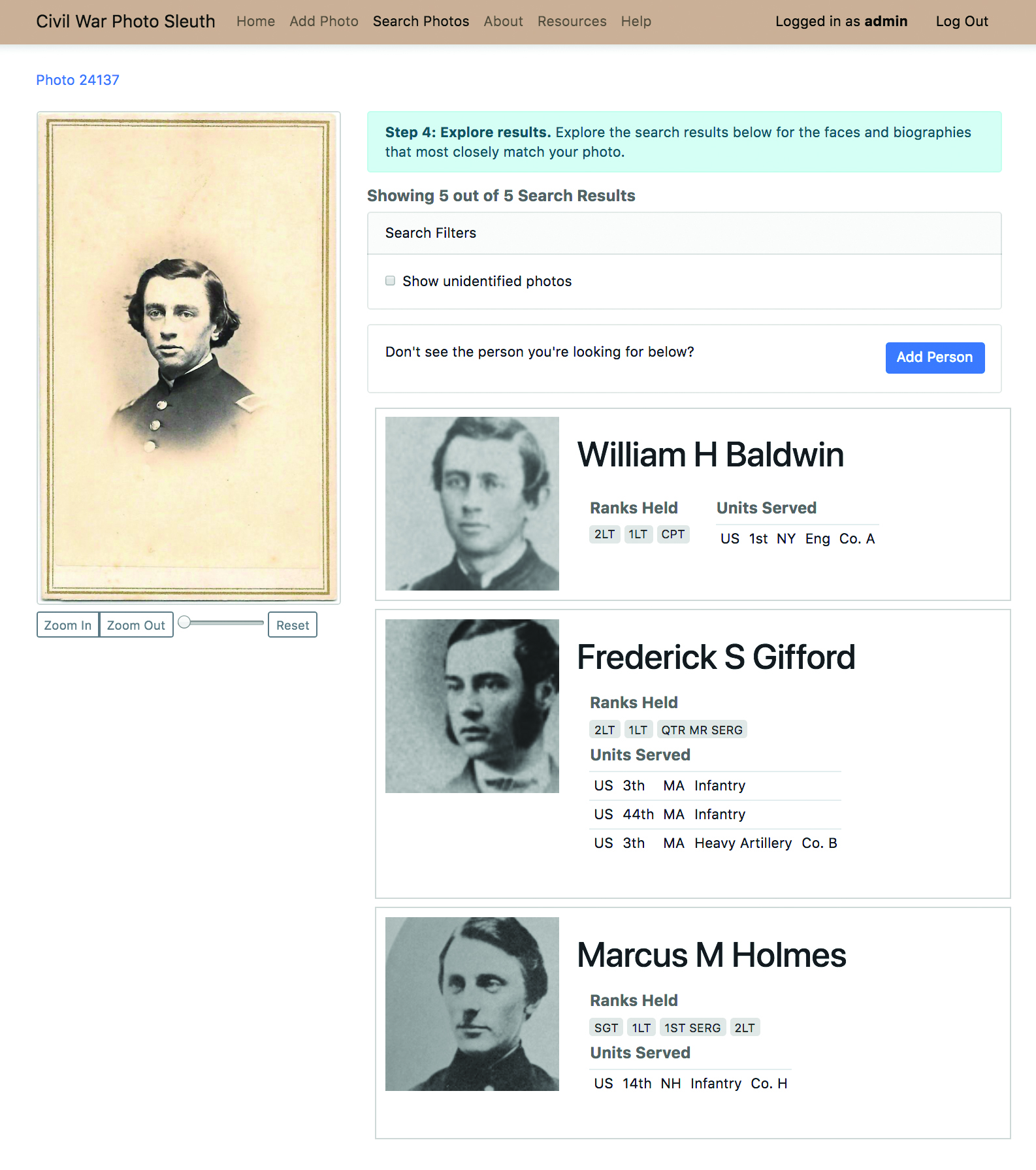

When users upload a photo onto the site, they can tick off tags about the color of the uniform coat, or at least whether it’s “dark” or “light,” to separate the Union and Confederate forces. The user can indicate whether the image has a “back mark,” which often had the photographer’s name and location, and whether there is a tax stamp — a key clue, as the government taxed photos from 1864-1866, to pay for the war. In addition, users are asked if there’s an insignia on the hat or collar, as well as whether they note stripes or chevrons on the uniform and how many, which can denote the man’s rank.

Similar to the viral Google app that found works of art that resembled users’ selfies, the facial recognition technology for Civil War Photo Sleuth uses a set of 27 facial landmarks, such as the corners of the mouth or the tip of the nose, to analyze a given photo. Faces have different proportions, so the software calculates various distances between facial landmarks in the uploaded portrait — such as the distance between left pupil and right pupil — and then looks for photos with similar distances between different facial features. (Sometimes discoloration or holes in such old images can obscure these facial landmarks and prevent identifications.)

The site then pulls up previously uploaded images that match the new one, with the hope that one of the matches will help identify the man in the picture.

The more photos are uploaded, the more likely a match will be found, and the Civil War Photo Sleuth team adds Library of Congress photos and other collections to enhance the probability of matches. Since launching in August 2018, nearly 30,000 photos have been added to the site by nearly 14,000 registered users, including employees at the Library of Congress and the National Archives. A little over 3,300 identifications have been made, including photos in the collections of the New York Public Library, the Massachusetts Historical Society and the Henry Ford museum in Michigan. The site also won Microsoft’s $25,000 Cloud AI Research Challenge and a National Science Foundation grant.

But despite the advanced technology, human research is still critical to confirming the app’s results. For example, when Morin uploaded a photo of an unidentified Union second lieutenant with a Manchester, N.H., back mark on the picture, he was surprised to see the site’s top recommended result was William H. Baldwin, who served in a New York engineering regiment instead of a New Hampshire regiment. Further research showed that he was from New Hampshire, but served in New York.

The system isn’t perfect: Identifications suggested by the site might be simply the best guesses of another uploader, and it’s unclear if every user has done follow-up research to confirm the identifications. But based on a study on one month’s activity, conducted by Luther and his team, the accuracy rate is estimated between 75% and 80%.

And collectors have a reason to want to expand the database, beyond mere curiosity, as identified photos sell better. “The image increases in value 50%,” says Tom Liljenquist, who collects for his family’s collection of more than 2,500 portraits.

Luther’s motives are also altruistic. The people behind the site hope that in identifying Civil War photos, they will also turn up new ways of telling this history — including, Coddington says, ways this technology can be applied to stories and photos of women and people of color, as the Civil War story is often told from the perspective of white Union soldiers.

“We went to war and it was devastating, and I can’t help but think that, if we were able to get exposed to these stories of the toll, the price that we paid for it,” Coddington says, “we might think differently about how we resolve our differences.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com