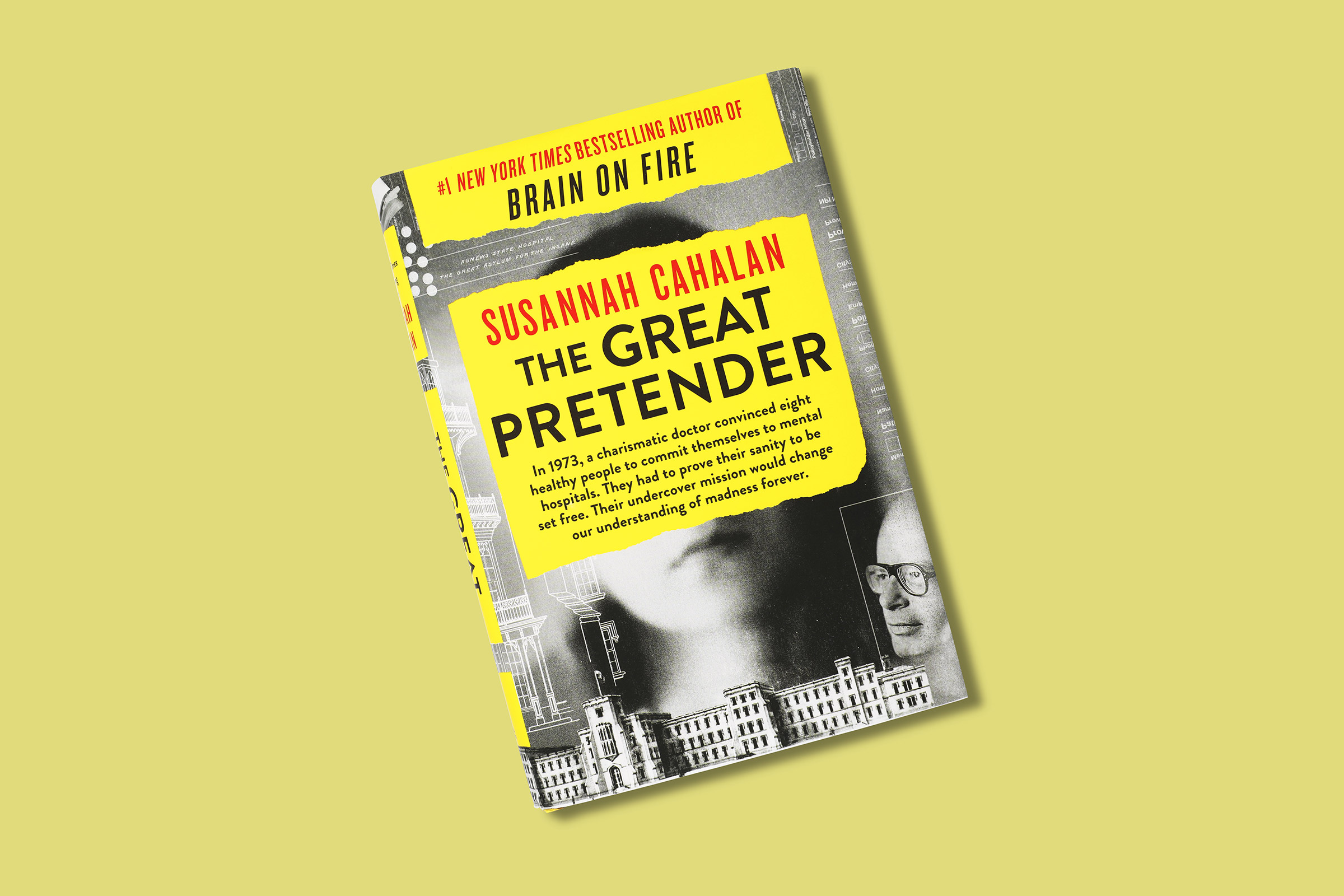

“If sanity and insanity exist, how shall we know them?” So begins a landmark 1973 study by Stanford psychology professor David Rosenhan, who persuaded eight healthy people to feign hallucinations and commit themselves to mental asylums. Once inside, they would have to prove their sanity to get out. The study’s impact was explosive, demonstrating that even trained professionals struggled to tell the difference between the mentally ill and the mentally healthy. It was so pivotal in reshaping our understanding and diagnosis of madness that 46 years later, it is still taught widely.

In The Great Pretender, journalist Susannah Cahalan turns her investigative skills to this famous experiment. Her interest in the trauma of being labeled insane is personal: at 24, she was hospitalized with symptoms including seizures, hallucinations and psychosis—an experience she recounted in her 2013 best seller, Brain on Fire. She was misdiagnosed with bipolar disorder before it emerged that she had a rare autoimmune disease of the brain. “For every miracle like me, there are…a thousand rotting away in jails or abandoned on the streets for the sin of being mentally ill,” she writes, “a million told that it’s all in their heads, as if our brains aren’t inside those heads.”

A gripping, insightful read, The Great Pretender probes the gaps that medical science has yet to fill when it comes to understanding mental illness. After recovering from her own condition, Cahalan spent five years exploring psychiatry. Rosenhan died in 2012, but Cahalan gained access to his notes. As she delved into them and searched for participants from the study, she discovered troubling inconsistencies in the work.

Even so, the accuracy of Rosenhan’s study comes to matter less than its consequences. After its publication, psychiatric hospitals all over the U.S. closed down. In tracing the history of psychiatric care in America, Cahalan charts how prisons have become the primary replacement for asylums—what she calls the “shadow mental-health care system”—and reminds us of the worrying influence of Big Pharma on the way we diagnose certain conditions.

The book has the urgency of a call to action: the U.S. is at least 95,000 public psychiatric beds short of need, and at least 20% of people in jails fit the criteria for serious mental illness. Having described the horrors of 19th century asylums, Cahalan delivers a bold verdict: “Today, it’s worse,” she writes. “We don’t even pretend the places we’re putting sick people aren’t hellholes.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Naina Bajekal at naina.bajekal@time.com