There’s a Time Machine in Vancouver. It’s a white box, 9 ft. high and 12 ft. wide, in a nondescript back room at the office of a publicly funded agency that one wouldn’t normally associate with science fiction. Step inside and you’re transported to the city’s past–1948 or thereabouts–able to explore a now razed neighborhood or a hotel demolished decades ago. No helmet or space suit is required. On April 23, you’ll be able to travel through space as well as time, when the machine opens to the public as part of the Tribeca Film Festival in New York City.

To be fair, this time machine doesn’t actually send you back in time, but it’s almost as cool as if it did. The box in question is part of Circa 1948, an interactive art installation created by the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) and artist Stan Douglas, who wanted to explore that tumultuous postwar period, when soldiers returned to a city facing a housing crisis and a burst of gentrification that threatened an older way of life. “I’m always looking at transitional moments in history, events with a capital E,” says Douglas, an award-winning Vancouverite whose work is in major museums around the world.

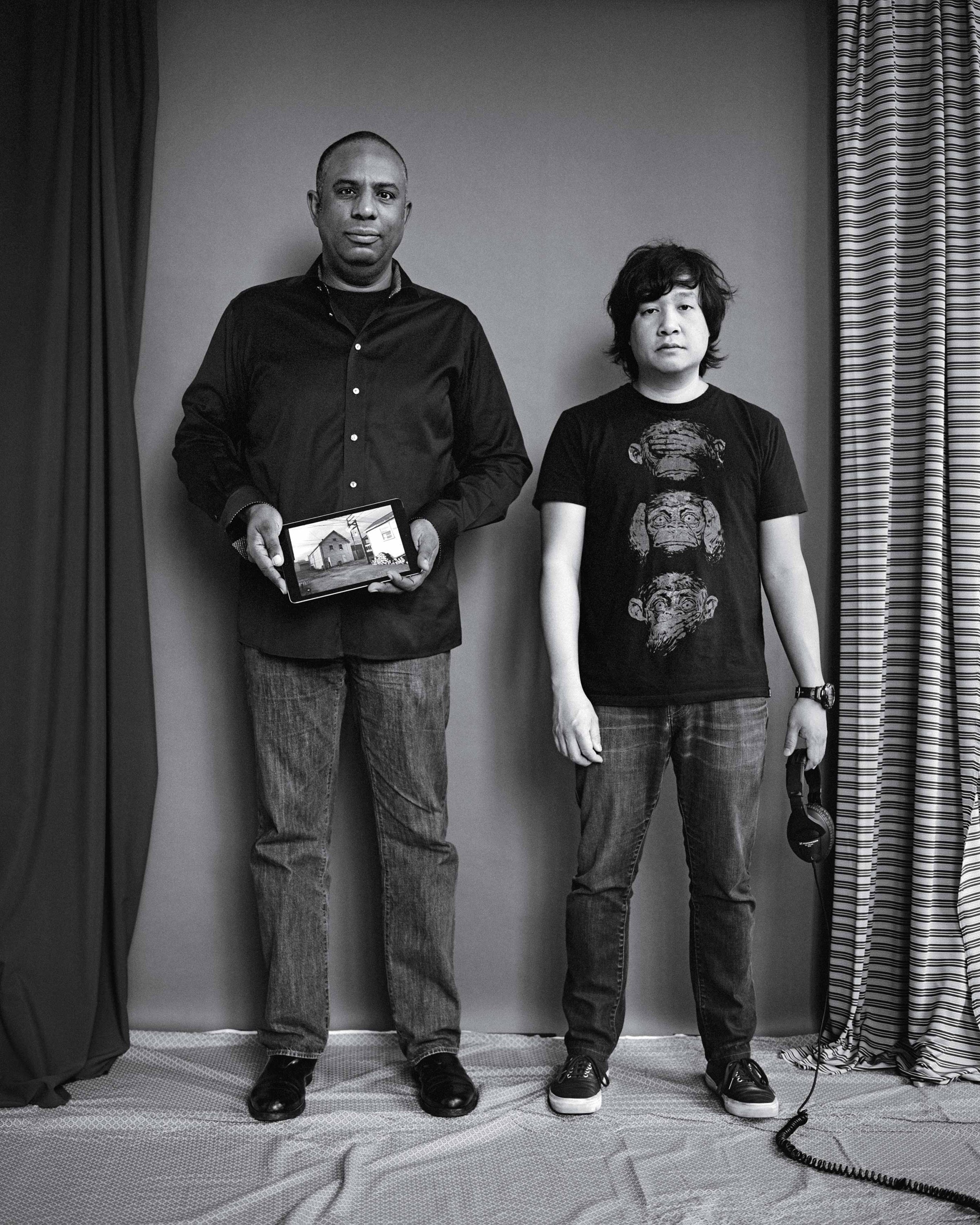

There are plenty of ways to visit the moment in question. Douglas and the NFB Digital Studio–led by Loc Dao, executive producer and “creative technologist”–will present the interactive installation at Tribeca’s second annual “Storyscapes” program, a four-day focus on cutting-edge work. (It opens at the tail end of the festival, which runs from April 16 to 27 this year.) There’s also an app for the iPad and iPhone, as well as a website, both of which launch April 22.

It’s too early to say whether right now is a transitional moment in history, but something’s up in the realm of film and technology. Moving pictures and linear plots have long dominated storytelling; they’re now ceding ground to new ideas like virtual reality and the kind of interactivity that used to be just for video games. With what may be its most ambitious project to date, the NFB–which celebrates its 75th birthday in May–is at the center of that transition.

Here’s how Circa 1948’s not-an-actual-time-machine works. After exhaustive research into Vancouver’s history, Douglas unearthed a trove of blueprints, maps and photographs that were traced by the NFB team into Maya, software that turned them into explorable 3-D renders that are meticulous re-creations of history. They’re photorealistic–detailed enough for the doors to have hinges–with varying resolutions used for each of the project’s different incarnations. The images can be small enough not to slow down your phone as you navigate through an old streetscape with the swipe of a finger–or big enough to seem real when you step into the full-body interactive experience. In the latter, each corner of the 12-ft.-wide frame is home to a Kinect camera array–the gadget best known for allowing gamers to do things like play virtual tennis–that detects the user’s position and adjusts the visuals accordingly. Take a step forward and the projections on the box’s walls move too.

But Douglas’ creation is no game; it’s a story, with characters and a plot. When you pause on a street corner or in a hotel lobby, certain locations trigger dialogue; the experience is more like eavesdropping than watching a movie. The snippets of conversation tie together the plot, but there’s no right order in which to experience it, so Douglas describes it as “recombinant.” (At Tribeca, in an April 22 live presentation, Douglas will walk viewers through one possible track.) Meanwhile, in a different format but using the same research, Douglas conceived a play, Helen Lawrence, which premiered in Vancouver in March and uses 3-D projections of those worlds instead of sets. In yet another incarnation, at Vancouver’s Presentation House Gallery, he’s exhibiting a still from the renderings the way one would a photo.

“Anyone working in interactive storytelling follows the NFB because their interactive digital studio has been doing such incredible work,” says Ingrid Kopp, Tribeca’s director of digital initiatives. “When I heard that Stan Douglas was involved, that was doubly exciting.”

Arranging all of these moving parts has been a big task for Douglas and the NFB, but not out of character. Just as Circa is a meticulously created replica of Vancouver in 1948, rendered so it can be seen from infinite angles, Douglas’ work previously has included mural-size photos that contain what can seem like infinite details. One example, Abbott and Cordova, 7 August 1971, captures a staged re-creation of a riot that took place at the intersection where the NFB’s office in Vancouver is housed; it now hangs in that very building’s atrium. Douglas describes such locations as “psycho-geographic places.” Similarly, the connection between past and present is central to the meaning and experience of Circa 1948.

Dao, who served as producer and co-creator of Circa 1948, and whose office is full of awards for his studio’s digital work, has spearheaded a long run of groundbreaking projects. In one recent example, Bear 71, his team created an interactive documentary by combining a voice-over with actual surveillance footage of a tagged wild grizzly; in 2013, it scored a Webby Award for Best NetArt. “Every project we do, we learn something new,” he says, “and we try to experiment with at least one new thing, working with story and form and technology.”

But when it comes to Circa, one form appears to be missing. Which raises a question: If the National Film Board made Circa possible and the Tribeca Film Festival is premiering the interactive element, where’s the film?

The answer to that question may not matter. More and more, as Circa shows, medium is subservient to story. Just as Douglas sees himself as a no-qualifiers-needed artist, rather than a specialist in any particular way of making art, it’s hard to even pin down what to call the medium in question. Each component of Circa lives in a landscape with a lexicon, but the words for the experience of the “storyworld” as a whole are still up for debate. As a wide range of media-consumption experiences migrate online or to mobile, that vocabulary is becoming more and more necessary. It’s not that all media have become singular–not every story is meant to be a 3-D app–but that the lines between them, even on the production and funding side, are blurring.

“I don’t think it’s accident that there’s more slippage,” says Tribeca’s Kopp. “One of the things that’s really exciting about this storytelling space is the collaboration across what used to be fairly solid disciplines.”

The slippage continues apace.

Virtual reality is having a moment, with Facebook’s recent blockbuster purchase of the company that makes the Oculus Rift, but Dao and the NFB predict that storytelling’s next move will go beyond wearables to a world where we experience that unreal reality without a device between us and the content. “We hope we’ll get to a time where technology is transparent in storytelling,” he says. “This is our step in that direction.”

That hope explains why Canada’s Parliament pays for the development of something as esoteric as an experimental, recombinant, interactive, 3-D, real-time world: this trip to the past is a glimpse at the future, a way to figure out how it works before it arrives.

It’s hard to calculate the cost of something like Circa, since much of the work is done by salaried employees, but its overall budget was about $850,000 Canadian. (The agency usually budgets up to $1.4 million per film and up to $560,000 for an interactive project.) Michelle van Beusekom, the acting general director of NFB’s English program, compares that investment to R&D at a science lab: the work may seem indulgent, but it can lead to practical discoveries.

The NFB’s mandate specifies a degree of social relevance for its work–the project must represent Canadians or help them understand their world–but there’s also economic motivation. As van Beusekom points out, commercial filmmaking enterprises often can’t afford to experiment with things like “transparent” virtual reality, but public funding provides the luxury of allowing new experimentation with every project. If the NFB and its safety net can make this work, then Canada’s for-profit film industry can use those discoveries too.

And then there’s the other reason for Canada’s citizens to invest in Circa 1948, the same reason anyone would want a time machine: to use it. “It’s selfish,” Douglas says. “I want to experience it myself. I want to experience midcentury Vancouver, this period of transformation–and so I worked with others to make that reality.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com