This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. A version of the article below was originally published at HNN.

The current clash in Congress over whether to impeach the President has extended to more than two centuries the bitter political partisanship that marked 11 previous presidential impeachment inquiries and the 1787 debate in Philadelphia over how to impeach the President.

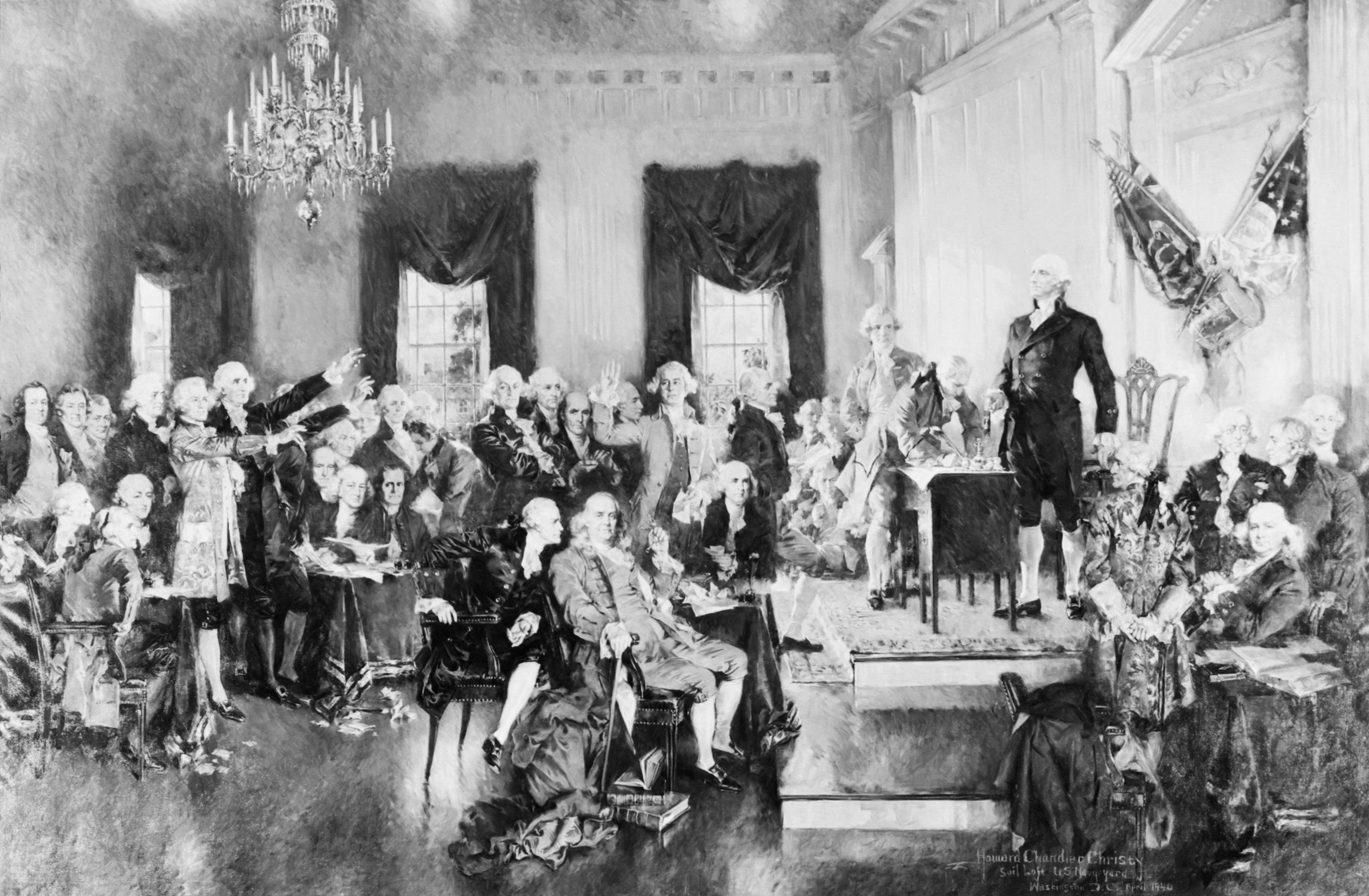

With windows of Pennsylvania’s State House (now Constitution Hall) sealed to ensure secrecy of the proceedings, the patience of sweltering delegates wore thin as July approached August. In rapid-fire succession, Massachusetts merchant Elbridge Gerry moved that the chief executive “be removable on impeachment and conviction for malpractice or neglect of duty.”

New York’s Gouverneur Morris scoffed at Gerry’s proposal and moved to strike it. But Virginia’s George Mason riposted, “No point is of more importance than that of the right of impeachment. Shall any man be above Justice…who can commit the most extensive injustice?”

As fruitless back-and-forth exchanges turned into a chorus of catcalls, all eyes turned to the venerable Benjamin Franklin for help:

“What was the practice before in cases where the chief magistrate rendered himself obnoxious?” asked the aging sage rhetorically. With his spectacles balanced precariously near the tip of his nose, he feigned careful thought, then answered his own question:

Why, recourse was had to assassination in which he was not only deprived of his life but of the opportunity of vindicating his character. It would be the best way therefore to provide in the Constitution for the regular punishment of the Executive where his misconduct should deserve it, and for his honorable acquittal when he should be unjustly accused.

As collective laughter filled the hall, tension eased, and Virginia’s diminutive James Madison, a planter’s son, joined the debate:

It is indispensable that some provision be made for defending the community against incapacity, negligence, or perfidy of the chief magistrate. The limitation of the period of his service is not a sufficient security. He might lose his capacity after his appointment. He might pervert his administration into a scheme of peculation or oppression. He might betray his trust to foreign powers.

South Carolina planter Charles Cotesworth Pinckney drawled that he could not see “or understand the need for any sort of impeachments.” The power to impeach would allow the legislature to hold “as a rod over the executive and by that means destroy his independence.”

Gerry shot up from his seat, barking that impeachments were essential. “A good magistrate will not fear them. A bad one ought to be kept in fear of them,” He pleaded with Congress not to adopt “the maxim that the chief magistrate could do no wrong.”

Virginia Governor Edmund Randolph agreed, calling impeachments “a favorite principle with me. Guilt, whenever found, ought to be punished. The executive will have great opportunities of abusing his power, particularly in time of war, when military force and in some respect the public money will be in his hands.”

New York’s Gouverneur Morris stood to say that arguments in favor of impeachment had convinced him “of the necessity of impeachments.

Our executive may be bribed by a greater interest to betray his trust, and no one would say that we ought to expose ourselves to the danger of seeing the first magistrate in foreign pay without being able to guard against it by displacing it…. The executive ought to be impeachable for treachery; corrupting his electors, and incapacity. He should be punished not as a man but as an officer and punished only by degradation from his office.

Morris climaxed his argument with a stirring assertion: “This Magistrate is not the king! The people are the king!”

On the question of ”Shall the Executive be removable on impeachment,” six states at the then voted “ay”—Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Vermont and South Carolina. South Carolina and Georgia voted “no.”

But the debate over impeachment had yet to resolve the question of what suspected crimes would be grounds for impeachment and who would try the accused executive. Members of the Convention reached a consensus, defining treason as “levying war against the United States or any of them; and in adhering to the enemies of the United States or any of them,” with at least two witnesses needed to convict. The definition of bribery seemed self-evident and was left without an explicit definition.

“Why,” George Mason interrupted, “is the [impeachment] provision restrained to treason and bribery?” Receiving no satisfactory answer, Mason answered his own question by moving to “extend the power of impeachments…to add maladministration.”

After Gouverneur Morris suggested that “election every four years will prevent maladministration,” Mason proposed ”high crimes and misdemeanors” instead. Eight states voted for the addition; New Jersey and Pennsylvania voted no.

It was not until Sept. 12 that the Convention approved a final draft of the Constitution, including Section 4 of Article II: “The President, Vice President and all civil officers of the United States, shall be removed from office on impeachment for, and conviction of, treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” With that, the Convention sent the Constitution to the states for ratification by ratification conventions in each state.

In the months that followed, eight states ratified, leaving only one more needed to establish a new nation. On June 2, 1788, the Virginia ratification convention came to order. Two days later, the legendary Patrick Henry, Virginia’s first governor, roared his objections: “As this government stands, I despise and abhor it. If your American chief be a man of ambition and abilities, how easy is it for him to render himself absolute!

My great objection to this government is that it does not leave us the means of…waging war against tyrants. The army is in his hands…. the president…can prescribe the terms on which he shall reign master…and what have you to oppose this force? What will then become of you and your rights?

Virginia’s Edmond Pendleton, the 67-year-old planter who chaired the convention, insisted that the proposed Constitution provided ample means to prevent tyranny: “We will assemble in convention” he explained, “recall our delegated powers, and punish those servants who have perverted powers…to their own emolument.”

Henry stared at the old man in disbelief: “O, Sir!” he replied softly. “We should have fine times indeed, if, to punish tyrants, it were only sufficient to assemble the people. Did you ever read of any revolution in any nation, brought about by the punishment of those in power, inflicted by those who had no power at all?”

Virginia’s convention ignored Henry’s objections, however, and voted to ratify the Constitution, but it left unanswered Henry’s question. After 230 years, the question still awaits an answer from Congress.

Harlow Giles Unger is author of 27 books, including a dozen biographies of the Founding Fathers. Among these is Lion of Liberty: Patrick Henry and the Call to a New Nation.

All quotations in this article at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia are from The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, Edited by Max Farrand (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 4 vols., 1966), II:63-70 (Friday, July 20, 1787) and Notes of Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787 Reported by James Madison (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Co., 1987), 331-336. The Patrick Henry and Edmund Pendleton quotations are from William Wirt Henry, Patrick Henry: Life, Correspondence and Speeches (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1891, 3 vols), 2:381-382.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com