Ali Wong broke out with a raunchy, layered take on feminism and motherhood in her Netflix specials Baby Cobra in 2016 and Hard Knock Wife two years later. She performed both while visibly pregnant, using her pregnancies as a jumping-off point for physical comedy and the themes explored in her standup. Next came the May 2019 romantic comedy Always Be My Maybe, which she produced, co-wrote and starred in alongside Randall Park (with a viral cameo by Keanu Reeves).

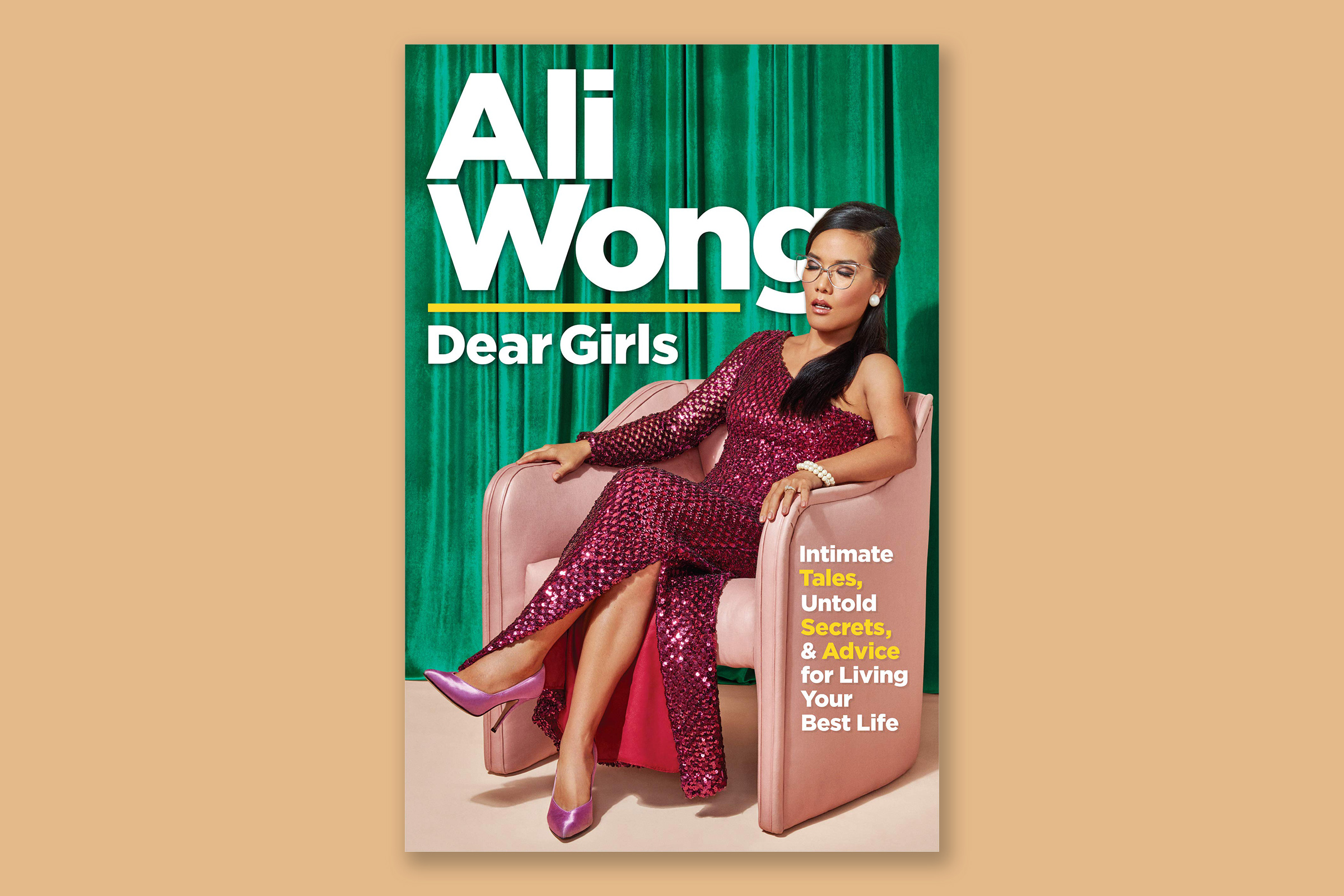

Now, Wong publishes her debut memoir, Dear Girls, a look at her personal and professional ups and downs, told in her hilarious signature voice. Addressed to the two daughters who appeared in her standup specials in utero — but far too explicit for them to read anytime soon — the book leaves no taboo or intimate topic untouched, from Wong’s sexual experimentations and misadventures in self-grooming to her heartbreaking miscarriage and the impact of her father’s death.

Wong spoke to TIME about life’s unpredictability, the power of couples’ therapy and the funniest things her daughters have ever done.

You’re used to writing for an audience. How is it different to write for a reader, alone in a room?

When my specials come out, for example this “Milk & Money” tour that I’m on right now — by the time I shoot that new hour, that show will have been performed already 100 times. I’m writing and performing the jokes in front of an audience constantly, so I know right away if it’s not working. With this book, I will find out if it’s working on Oct. 15 and thereafter. The debut is a lot more high stakes.

Are you nervous?

I’m very nervous. The other thing is that Netflix is notorious for not releasing its metrics, so I don’t know how many people actually watched the specials. They did release info about [Always Be My Maybe] — in the first four weeks 32 million people watched that movie. But it wasn’t the same as going into a theater and selling tickets. For the book it’s very different.

The book is constructed as a set of letters to your two daughters. Do you picture handing it to them when they’re a certain age and saying, “O.K., you can read this now”?

It’s funny to pretend that I have any control over when they read it. I lost my virginity when I was like 15 — you read about all the bad stuff I did. Kids grow up as fast as they want to. If they want to come to my stand-up shows or watch the specials I will be so, so flattered. I have friends who are arguably some of the best comedians of our time, and their kids don’t think they’re funny.

What’s the funniest thing your daughters have done?

It’s hard to describe how funny this is but when my oldest daughter was maybe one and half, she did this thing where she would fart and immediately she’d look at me and say, “No.” And it was serious. She wouldn’t laugh or anything. But her timing was so good. She would catch it right at the tail end of the fart where she would be like, “No.”

Who’s funnier — you or them?

I don’t think anyone’s going to buy a ticket to watch them do standup, but there’s certainly a lot of ways in which they make me laugh so hard. Comedy is not about making people laugh all the time. It’s also about surprising people. We have a family friend who wears glasses and she’s older and has brown hair and a very pointy chin and nose. We’ll call her Tanya. And my daughter saw a picture of Michael Moore and she was like, “Is that Tanya?” We didn’t realize he looked exactly like Tanya. We laughed so hard.

You’re so direct about your body and sexuality in the book. How are you planning to talk to your kids about these topics?

I came from this really atypical Asian-American family. My parents were not focused on academics. If I got a bad grade, they weren’t that upset. In terms of sex, my parents were always really open. So I’ll probably do the same thing. But I don’t know, my kids are under four and I’m just trying to get them to not choke on stuff right now. Like little bobby pins that are lying around or whatever I’ve dropped on the floor.

True, it is so much easier to make plans than it is to really understand what it takes to follow through on them or what that circumstance is going to be like when you get there.

Right — I had this very specific idea of how I wanted to give birth. I had literally signed up with this lady to turn my placenta into pills and we were going to get a test to make sure that I didn’t have any diseases that would threaten the person who was making the pills. And then I had to get induced and get a C-section, which was not what I wanted. But you can’t plan it. It was a great exercise in improvising and adjusting and becoming more adaptable.

You write about how you struggled being the youngest child and having older parents, and what it was like to lose your father. How did that change you?

It changed my relationship with my mother so much because I ask her so many more questions about who she was before she became a mother. I ask her about dating and how she thought about her career and moving to the U.S. I just wish I had asked my dad all those questions.

I get really melancholy about the fact that my dad will never meet my kids, and I do feel envious that he got to meet my niece and nephews, that there are pictures of them with my father. I think about him and my mom and how in their retirement they would have loved going on tour with me and my kids. He would have loved going to all these different cities, meeting all these different people. God, he would have loved the movie premiere. I just thought of that. He would have read all of these articles and he would have pasted them all on his wall and looked like a person who was obsessed with me who was going to kill me. It would have been like that Claire Danes Homeland wall. But I think less about him witnessing everything in my career, mostly just witnessing my kids and having a relationship with them and talking to them. And in terms of how it affected me, I would say that that’s the reason why I had kids when I did, too. I could not afford to wait for my career to take off. I do not want to be an old parent.

Your name recently got pulled into a conversation about Shane Gillis’ firing from Saturday Night Live for racist comments made before he was hired. What did you make of that?

I had just heard that recently. I can’t really speak about that situation because I never read the article or watched the clips. And I don’t think I ever will. I’m just not interested.

What would you say to people who think it’s O.K. to make jokes at the expense of others?

It’s really not about topic choice, it’s about word choice. It takes a great joke-crafter to put things in a context that makes people laugh. If people are cringing more than laughing, then it’s not the topic that’s wrong, it’s probably the way you worded your joke. When fashion designers come up with their collections, you’re not like, “What materials are off-limits?” It’s all about how they cut the fabric and style it. I wish people would give the same credit to comedians. It’s frustrating for me to talk about, because breaking it down, the answer is that there is no right answer. Otherwise everyone would be a standup comedian. It all comes down to instinct.

Dear Girls ends with a letter by your husband, Justin Hakuta. Why was it important to give him space to speak for himself?

I was really inspired when I read [Paul Kalanithi’s] When Breath Becomes Air. His wife writes the afterword, and it’s incredible. For my book I thought it would be nice because he never gets to say anything. He never gets to clap back at me. I asked him, and he was game right away. I joke about him a lot, but he’s obviously a very important contributor to everything that I have now.

You’re open about going to therapy together. Should we all be in couple’s therapy?

Well, I live in Los Angeles where everyone is in some kind of therapy. You know how online dating used to be all taboo and shameful? Now tons of people have met online. And now I feel like everyone’s in therapy. I don’t see how for us we could not go to couple’s therapy within the first two, three years of having kids. For us it’s been really important, and for other people, if you don’t go to couple’s therapy I hope you have great communication skills. You never know what’s going on in other people’s relationships. I’m 37, so sh-t’s starting to hit the fan. People are starting to get divorced, and it’s the people who are least expected. Things seemed so great on the outside.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lucy Feldman at lucy.feldman@time.com