This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. A version of the article below was originally published at HNN.

Fears that Russian intelligence is actively working to undermine Western democracy—in the United States, Europe and around the globe—are running high. Department of Justice Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller III documented multiple systemic interferences by Russia in his report on the 2016 presidential election released earlier this year, and he warned that Russia is actively targeting the 2020 election. Similarly, Russia conducted a “continued and sustained” disinformation campaign against Europe’s parliamentary elections in May, according to a European Union report. Techniques include planting false news stories, hacking into campaign accounts, creating fake social media accounts and using software applications known as bots to spread distorted, divisive content.

While Russian bots and fake Facebook accounts are relatively new, efforts to undercut Western values and democracy and sow division among allies have long been part of the playbook for Russian and Soviet intelligence. One of the highest-stakes attempts came 60 years ago. On Nov. 10, 1958, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev fired the opening salvo of what would become known as the Berlin Crisis, a gambit meant to force the Western powers to pull their troops out of the divided city. Khrushchev declared that Soviet forces would withdraw from the city, and pressured the Americans, British and French to follow suit. In effect, it was a demand that the Western powers relinquish their right of access to Berlin that had been agreed to at the end of World War II. Doing so would mean abandoning West Berlin, which was surrounded by East German territory.

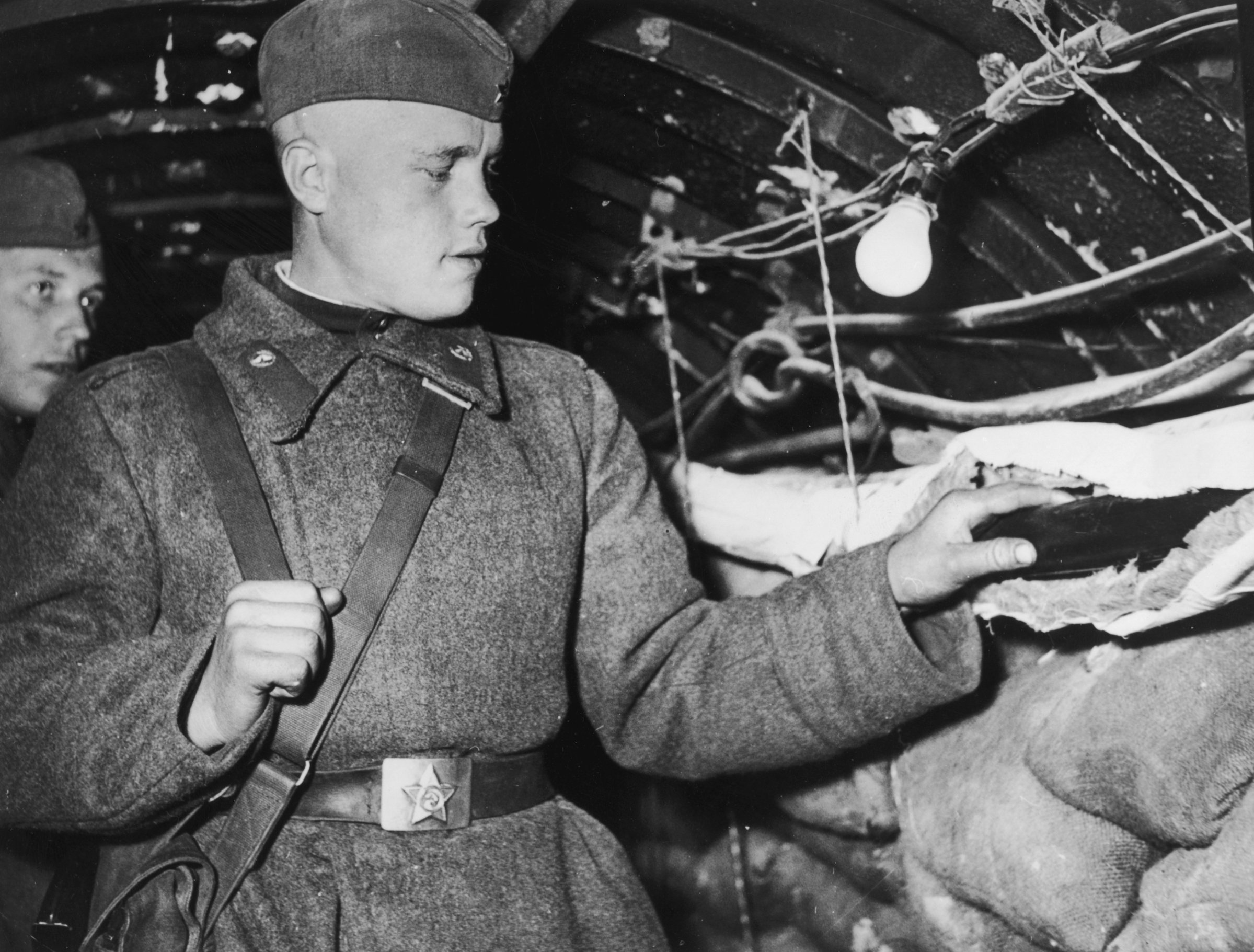

Not unlike the current Russian efforts to undermine public trust in democracy, behind the scenes, the KGB waged a determined campaign using propaganda and disinformation to paint the Americans as cynical occupiers interested in Berlin only as a base for nefarious espionage operations that were oppressing the German people. The Soviets charged that West Berlin was a “nest of spies” and its victims were the citizens of both East and West Berlin. Exhibit A was the Berlin Tunnel. The audacious joint operation, by the CIA’s Berlin base chief Bill Harvey and Peter Lunn, chief of the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) Berlin station, involved digging a secret, quarter-mile-long tunnel from the American sector into the Soviet sector to tap into Red Army communications. Though the KGB had been tipped off about plans for the tunnel by the notorious spy George Blake, the intelligence service took no action against the tunnel. They Soviets didn’t even warn Red Army commanders, for fear of compromising Blake, as described in Betrayal in Berlin. For nearly a year, from May 1955 until the Soviets announced they had discovered the tunnel in April 1956, CIA and SIS captured reams of material about Soviet military capabilities, operations and plans, as well as information from GRU (Soviet military intelligence), KGB and East German intelligence offices using the tapped lines.

Ironically, the U.S. was able to counter the KGB campaign against Western espionage– thanks to intelligence gathered by Berlin Tunnel. As the tension surrounding the crisis grew in late 1958 when Khrushchev laid out his demands, the CIA base in Berlin went to work compiling information about Soviet intelligence transgressions.

Khrushchev’s formal ultimatum calling for the withdrawal of the four powers from Berlin, delivered in Moscow on Nov. 27, 1958, set a six-month deadline. Otherwise, he warned, the Soviet Union would sign a separate peace treaty with East Germany and cede control of access to the city to the East German regime, steps that could effectively end West Berlin’s status as a free city. Berlin is a “malignant tumor,” Khrushchev declared in his speech at the Moscow Sports Palace. “We have decided to do some surgery.”

In one fell swoop, U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower later said, Khrushchev had turned Berlin “into a tinderbox.” On New Year’s Eve 1958, the Allies officially rejected the Soviet demand, setting the stage for a dangerous confrontation.

Disinformation—disinformazia—had long been a staple of Soviet intelligence, but the KGB had begun throwing more resources into their efforts. In January 1959, Aleksandr Shelepin, who had recently taken over as head of the KGB, established a new organization, Department D, to create and coordinate disinformation programs. Department D’s first priority was West Berlin. The KGB had recently discovered that a Soviet military intelligence officer, Pyotr Popov, was spying for the CIA. Combined with the impressive scale of the tunnel, the KGB considered the CIA’s Berlin base a major security threat that needed to be neutralized. “This unit [is] headed by the American Bill Harvey, known by the nickname ‘Big Bill’,” a KGB memorandum said. “. . . The available material provides a basis for assuming that ‘Big Bill’ and his coworkers carry out active intelligence work against the countries of the Socialist camp, for which they have a large agent network.”

Resuming the same propaganda strategy that followed the discovery of the tunnel, the KGB launched a new campaign portraying West Berlin as an espionage swamp and center of subversive activities. A key goal was to damage public support for the U.S. among the populations of other Western nations.

The U.S. State Department feared that the Soviet campaign might undercut Western solidarity about not abandoning Berlin at talks scheduled to begin in Geneva in May 1959 between foreign ministers from the four powers in an attempt to defuse the crisis. John Foster Dulles, terminally ill with cancer, had resigned as Secretary of State in April, and had been succeeded by Under Secretary of State Christian Herter. The former Massachusetts governor and congressman would be facing off against the formidable Andrei Gromyko, near the start of a nearly three-decade career as Soviet foreign minister.

In preparation for the summit, the CIA’s Berlin Operations Base prepared a counterattack listing a long catalog of Soviet and East German espionage and covert operations run from East Berlin, many of them discovered by the tunnel. “Now that the tunnel was no longer running, we could use it all, and we did,” recalled David Murphy, who was then deputy chief of the base. The CIA provided Herter and his aides with lengthy memos detailing the eastern espionage operations.

After a month of tense talks in Geneva amid Soviet accusations about West Berlin, Herter made his move June 5 at a forum attended by the press. Herter confronted Gromyko with the evidence, charging that East Berlin was “one of the heaviest concentrations of subversive and spying activities in the world.”

The American painstakingly recited the litany of evidence compiled by the CIA. He told Gromyko that it was “reliably estimated” that the Soviets had “26,000 officers, directing more than 200,000 agents and informers” operating in West Berlin, West Germany and elsewhere in Western Europe. He accused the Soviets of responsibility for 63 kidnappings of defectors, activists, and others in West Berlin opposed to the East German regime, most of the cases involving “brute force.”

Herter further charged that the Soviets were using East Berlin as “the center of an extensive campaign of slanderous personal vilification” against Western officials, sending anonymous letters to the spouses of Allied officials and German civilians implying their husbands or wives were unfaithful. He accused them of spreading lies and rumors through whispering campaigns—what then passed for social media.

“The goal of this centrally directed effort at subversion is the complete overthrow of the existing constitutional and social order” in West Germany, Herter charged.

Gromyko “sat there for two hours while the Secretary of State read him word by word every single thing from these memoranda about Soviet and East German intelligence operations in East Berlin,” recalled Murphy. “It was the first time that we used counterintelligence material [to publicly confront the Soviets], and we were able to do it because the tunnel provided it to us.”

Gromyko was “stony-faced through the recital,” according to one account, while the rest of the Soviet delegation “acted pained and aggrieved.” Finally, Gromyko responded that the Soviet file on Western spying in Berlin was “much more comprehensive” than the American list, but he needed to give only one example: “the matter of the tunnel dug from West to East Berlin.”

It was certainly a valid point.

But the elaborate American presentation was widely reported by the Western press, with numerous articles highlighting the vast scale of Soviet espionage operations against the West. Herter reported to the president that the counterattack “shook Gromyko up a bit” and had blunted the Soviet campaign. “We may hear very little more about it,” the Secretary of State predicted to Eisenhower.

Meanwhile, Khrushchev proved unwilling to go to war over Berlin, and the six-month deadline he had set for Western withdrawal passed virtually unnoticed. “It was the ultimatum that, only a few months before, many had feared would bring up the curtain of World War III,” Eisenhower later wrote. “The day came and went—a day lost in history.” But as Eisenhower well knew, the Berlin problem was hardly solved.

Three years later, with Khrushchev’s consent, the East German regime led by Walter Ulbricht constructed the Berlin Wall in August 1961. With free access across the sector borders closed, Berlin was effectively shut down as an espionage center. But it came at an enormous cost to the Soviet and East German regimes. Any pretense that the communist governments were defending the freedom of those behind the Iron Curtain was gone.

When the Berlin Wall finally fell 30 years ago, a development soon followed by the collapse of the Soviet Union, many celebrated what was widely seen as the final and complete triumph of liberal democracy in the Western world. But as the warnings of Russian interference from the recent reports by Mueller and the European Union make clear, that battle is ongoing.

Journalist and author Steve Vogel reported for the Washington Post for more than 20 years, writing frequently about defense issues. His latest book, BETRAYAL IN BERLIN: The True Story of the Cold War’s Most Audacious Espionage Operation, was published Sept. 24 by Custom House.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com