Carter Roberts’ motorized wheelchair didn’t arrive until the day he died.

It had been a long time coming and his parents had fought hard to get it. The chair cost more than $32,000 and the insurance companies wouldn’t cover it, so the family went to court. One insurer eventually agreed to pay for some components of the chair but not the whole thing. And then none of it mattered anyway. On Sept. 22, 2018, the Roberts’ doorbell rang and the chair was delivered. Also on Sept. 22, 2018, Carter died, just three months shy of his sixth birthday. He had been largely paralyzed for the final two years of his life. The family is only now beginning to pick their way through the horror of what happened.

“Our eight-year-old daughter believes she can speak to him,” says Carter’s mother Robin. “She was playing video games the other day and she’s looking up and going, ‘Carter are you seeing this? I need your help.’”

By any measure, the Roberts family of Richmond, Va. was spectacularly unlucky. They lost their son to a disease that science first recognized only in 2012. It’s new enough that it didn’t even have a formally accepted name until 2014. When it got one, it was one of those names that is more or less just a clinical description of what the disease is: acute flaccid myelitis (AFM), a sudden inflammation of spinal tissue resulting in flaccid paralysis of the muscles of the limbs, neck, face and often diaphragm. It’s a lot like polio but it’s not polio; it’s a little like meningitis and Guillain-Barré syndrome but it’s not them either.

Indeed, no one knows exactly what it is. For the moment it remains rare: In the U.S., where AFM is closely tracked, the disease attacks fewer than one in a million people even in peak years, and it very rarely kills. But in the past seven years, it’s been striking more and killing more, and there is a tick-tock certainty to when it will hit next. As with polio, AFM is seasonal—though unlike polio, it arrives in late summer and early to mid fall, rather than in the spring and summer. Also unlike polio, it runs in an every-other-year cycle, peaking in even-numbered years.

While spotty outbreaks of AFM have been retrospectively diagnosed in the U.S. from 2005 to 2012, it was in 2014 that the disease established its current pattern. That year, there were 120 confirmed cases scattered around the country; in 2015, the total fell to 22 cases; it climbed again in 2016 to 149 cases; fell again in 2017 to 35 cases and jumped back up last year to 201 cases. So far in 2019, there have been 20 cases of AFM in nine states.

Now, as an even-numbered year inevitably approaches, there is a growing feeling of looming menace. When 2020 arrives—and then 2022 and 2024 and on into the future—more and more children are destined to be claimed, unless science gets a handle on the disease fast.

“This is our generation’s polio,” Carter’s mother, Robin Roberts says flatly.

That’s not just the opinion of a grieving mother; doctors admit to feeling daunted too. “I can’t think of a single disease that had this pattern that we’re seeing, with modern laboratory diagnostics not figuring it out,” says Dr. Nancy Messonnier, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

As with polio too, the medical community has mobilized. Back in the 1930s through 1950s, the work was led by the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, the non-governmental consortium of scientists that included Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin, who developed the two different versions of the polio vaccine. This time it’s the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which last fall formed a task force consisting principally of 17 epidemiologists, neurologists, pediatricians and other experts from teaching hospitals and health departments across 10 states, as well as from the National Institutes of Health and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

The task force had its first meeting in December 2018 at the CDC’s headquarters in Atlanta, and the gathering had the feeling of a war council. Every seat at a massive conference table in a windowless room was full, with doctors and other staffers lining the walls and epidemiological maps and graphics on display screens.

“This is obviously complicated or we wouldn’t be in this place,” said Messonnier in her opening remarks.

Lending urgency to the task force’s work is that AFM seems not only to be getting stronger, but crueler too. As recently as 2014, the median age of AFM victims was seven years old; then it fell to five and now it’s just four and a half—kindergarteners. Like polio, it strikes at just the point when children are fairly defined by their happy, kinetic energy—and then it takes it away from them.

“It was kind of surreal to be like, ‘Wait, how rare is this? One in a million? You’ve got to be kidding me,’” says Jeremy Wilcox of Herndon, Va., whose four-year-old son Joey contracted AFM in September 2018 and lost the ability to walk, but has largely—though not entirely—recovered.

Roberts and Wilcox were in Atlanta in December to address the task force. Their ostensible purpose that day was to describe the nature of the disease to the doctors, who at this point understand it far less well than the lay families living its terrors. But the more pressing and powerful reason was to humanize the problem—to establish the mortal urgency of solving it.

“AFM has changed my life,” says Rachel Scott, mother of a third child, Braden, who is battling the disease, and who also attended the meeting. “It’s changed my children’s lives; they’re growing up in a completely different world than they would have. This is not something I ever would have dreamed of.”

Braden Scott, whose family lives in Woodlands, Texas, first came down with what seemed like a routine summer cold on July 4, 2016. But the next day, when he tried to eat so much as a single potato chip, he couldn’t keep it down—not because his stomach was upset, but because the muscles that control swallowing had begun to fail. “He got weaker over the next few days and we came to realize his swallowing was paralyzed,” says Rachel.

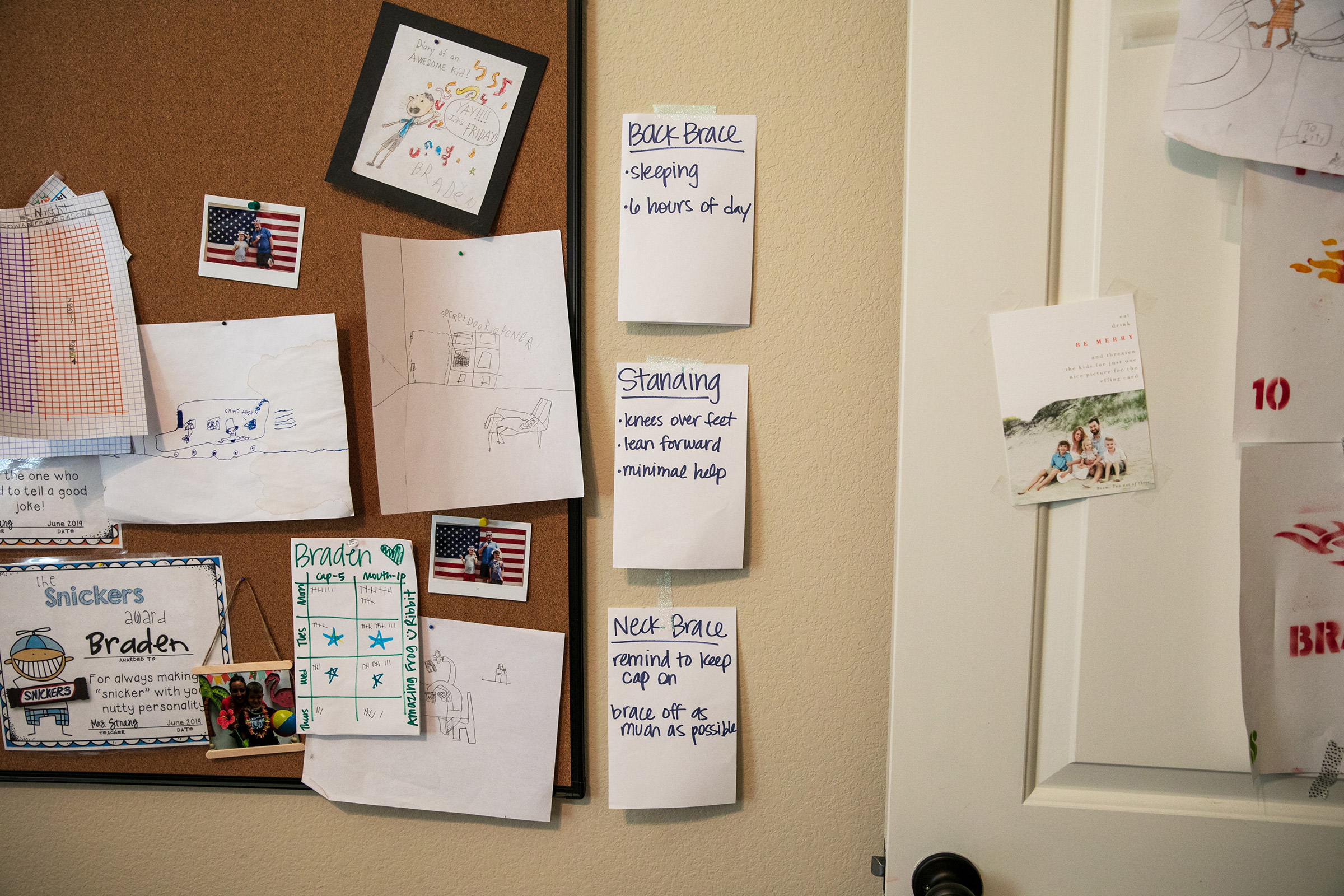

Eventually, the paralysis spread throughout Braden’s entire body below the neck, including his diaphragm, which meant he had to be intubated in order to breathe. He spent seven months in the hospital as the most acute phase of the disease receded and he received in-patient rehab, but even now that he’s home, his walking remains unsteady, paralysis continues in his left arm and his swallowing is still so poor he must be fed a liquid nutrient four times a day through a port in his stomach. Merely controlling his swallowing enough to clear saliva is a challenge, and though he’s back in school, a nurse who accompanies him must periodically suction his mouth so that he doesn’t choke.

“Every day when he comes home from school, we say, ‘OK, how many mouth suctions today?’” says Rachel. “Sometimes it’s only three and we’re like, ‘That’s amazing!’ The things I celebrate are absurd.”

Like so many AFM patients, Braden was at first misdiagnosed. When his parents rushed him to the hospital with fever and spreading paralysis, the doctors said his problem was mononucleosis and strep; they prescribed him antibiotics and steroids and sent him home. Joey Wilcox was first suspected of having Bell’s Palsy—his face was partly paralyzed, so what else could it be? The doctors eventually sent him home with no medicine and a vague diagnosis of a virus, one they said was likely to pass on its own. Carter Roberts’ family was told that he was merely tired and needed rest.

In many cases, the correct diagnosis doesn’t come until full paralysis has set in and doctors finally conduct an MRI of the spinal cord looking for a lesion or some other localized explanation. By that point, the extent of the disease can be startling. “Carter’s cord was so inflamed they couldn’t even distinguish between gray matter and white matter,” says Roberts.

If the damage AFM does shows up clearly on a scan, the cause of the disease doesn’t leave clear fingerprints, though experts have good reason to believe it’s a viral illness. Its seasonality is consistent with viral behavior—the way colds and flus strike in the fall and winter and polio in the spring. The biannual peaks are not unusual for a virus either. “Measles before vaccination was every two years as well,” says Dr. Thomas Clark, the CDC’s AFM Incident Manager.

But measles—and polio, chicken pox, rubella, and other childhood viral diseases—are very different infectious beasts because they are all caused by a discrete virus, which can be detected in the blood and neutralized by vaccination. AFM is murkier. It’s thought to be associated with at least two different enteroviruses—viruses that incubate in the gut. There are hundreds of enteroviruses (including polio and influenza), and so far the ones designated EV-D68 and EV-A71 have been most widely implicated in AFM paralysis. But “widely” is not even close to “universally.”

During peak years, no more than 30% of AFM patients show some traces of EV-D68; another third show EV-A71 or other stray viruses; another third show nothing at all.

Even if the two enteroviruses turn out to be to blame, no one knows exactly how they do their damage. While the poliovirus directly attacks the ventral horn cells in the spinal column, it’s entirely unclear what EV-D68 and EV-A71 do to the central nervous system. The best analogy might be to Guillain-Barré, an inflammation of the peripheral nervous system that usually results from a misfiring of the immune system after an infection with a stomach or respiratory virus.

The mention of Guillain-Barré predictably gets the anti-vaccine crowd chattering, since a slight increase in the risk of the disease has been observed among people who receive the flu vaccine—on the order of one or two additional cases for every million vaccinations. (The CDC stresses that the risks associated with severe influenza—including death—are far worse than the far smaller risk of Guillain-Barré.) There is no evidence at all of any link between AFM and any vaccine, but the CDC all the same is investigating any possible connection, simply because good epidemiological sleuthing requires no possibility be overlooked.

“We’ve always thoroughly looked at vaccine safety in all of our programs,” says Patel. “Currently, we don’t have any evidence to suggest that there is an association.” Clark adds that the children who have developed AFM have generally been vaccinated in the same way and on the same schedule as the tens of millions of children who don’t get sick.

The more epidemiological avenues that reach a dead end, the more researchers are concluding that they are coming up against a disease more complex than they reckoned. “AFM can’t have a simple answer because if it was, all these smart people would have figured it out,” says the CDC’s Messonnier.

What alarms the CDC is the possibility that the medical community could face wave of cases before that figuring out can happen, and polio offers a precedent. The earliest documented polio outbreaks were mild: four cases in the U.K. in 1835; ten in Louisiana in 1835. In 1894, a major outbreak struck Vermont, when 132 children fell sick—and after that, the disease exploded. There was an epidemic of 27,000 cases in the U.S. in 1916, including 9,300 in New York City alone. In the years after, there were thousands—sometimes tens of thousands—of cases every summer in the U.S., with the peak coming in 1952, when 57,879 polio infections were recorded. The epidemiological fever didn’t break until 1955 when the first polio vaccine was approved.

If there are similarities in the AFM and polio infectious profile, there are big differences in the prognoses. Polio paralysis always seemed intractable—sudden and effectively permanent—while AFM patients can regain much of their function. That may say less about the infectious agent and more about the therapeutic options that are available in the 21st century and weren’t in the 19th and 20th.

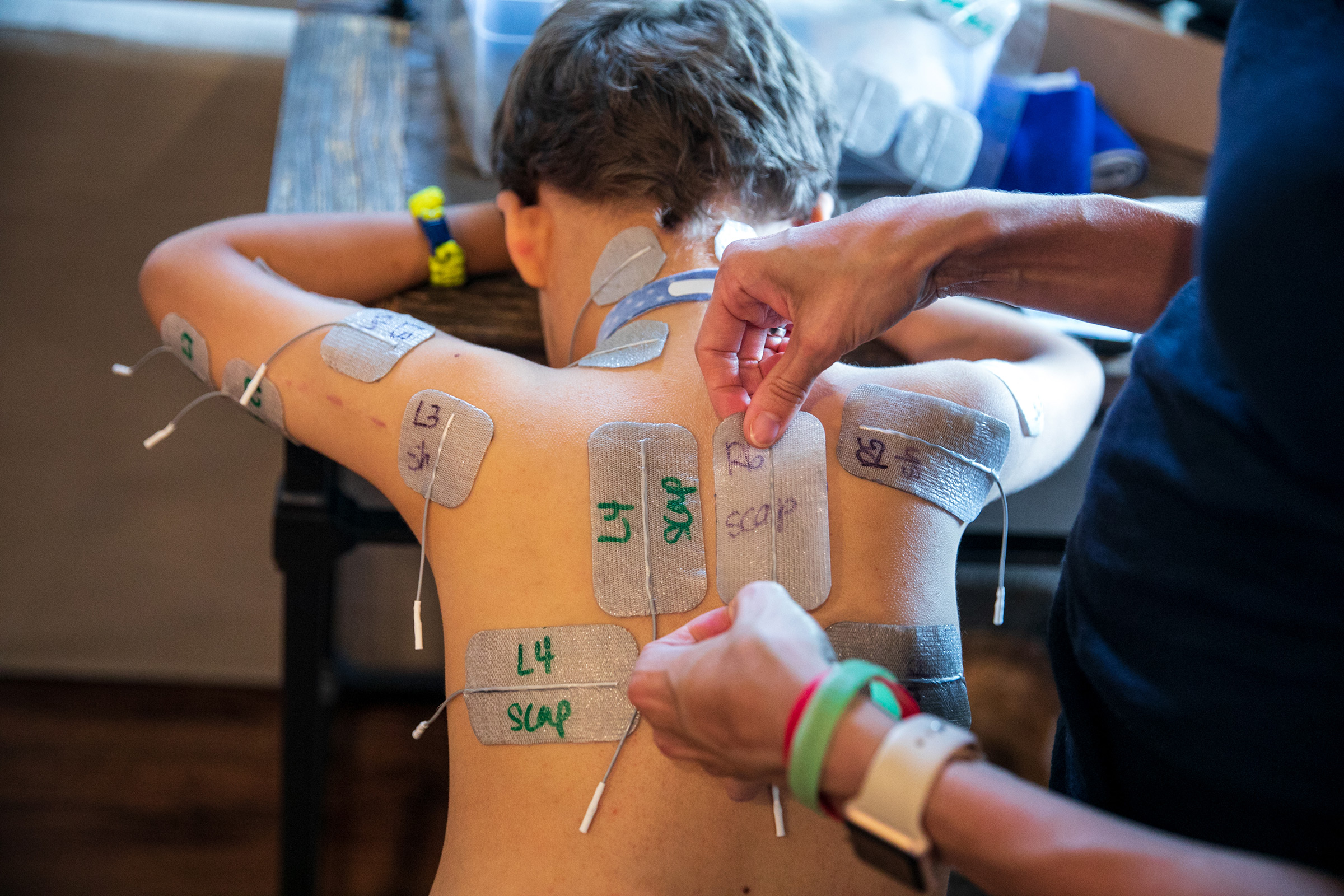

Patients have access to a far better array of prostheses and far more thorough physical therapy programs than they would have 100 or even 50 years ago, with kids today sometimes working up to five and six hours a day to regain mobility. Braden Scott receives regular muscle therapy, which he refers to as “zapping,” and it’s a fair enough term for what the seven year old goes through several times a week. In each session, medical technicians paste 48 electrodes to his arms and legs, which send synchronized signals to various muscle groups mimicking the electrical commands the brain would normally send the muscles to get them moving. Regardless of the source of the signal, the impact on the muscles is the same: the motion serves as exercise, preventing the atrophy that can occur when a limb is unused. The nervous system benefits too, with the signal channel between the spine and the limb remaining open.

Braden also underwent a relatively new surgical protocol known as nerve transfer, in which a healthy donor nerve from elsewhere in his body was left connected to the spinal cord but was rethreaded to his left arm, where AFM destroyed an existing nerve. Three years out from his symptoms, he continues to improve—but slowly. The tracheostomy tube that helped him breathe will soon come out, but his improvement in eating and swallowing normally—which takes the complex interplay of multiple muscles in the head and neck, as well as coordination with the throat to protect the trachea—has been much slower.

Inevitably in the U.S., any disease—especially a newly identified one with treatment protocols that are by definition unproven—will run into the wall of the health insurance system, with parents dividing their time and energy between tending their sick child and fighting simply to get coverage.

“It’s hell,” says Roberts, who battled for the wheelchair that came too late for her son. “You’re just dropped blindly in the middle of a labyrinth that is health care. You’re grasping at walls and corners trying to feel your way out, and no one is willing to hold your hand or give you a GPS.”

Toward the end of Carter’s life, his doctors recommended a drug to ease his breathing, but the insurance company refused to pay for that, too. “I pushed back as far as I possibly could until a final denial after eight months,” says Roberts. She wonders to this day whether the drug would have made a difference.

Joey Wilcox has mostly recovered, a year out from his initial symptoms. He still has some paralysis on the left side of his face and a bit of a limp in his right leg, but when he first got sick, he was so weak he referred to himself as a “floppy human.”

“I’m thinking it may have come from a video game,” says his father, Jeremy. “He said, ‘Am I always going to be a floppy human?’ My wife said no. I didn’t answer and I don’t know if I would have given the right answer because saying to your child, ‘I don’t know’ is not comforting or reassuring.” If medical history is a guide, comfort does come, reassurance does come—cures and vaccines do come. But they come only with time and only with work—as the calendar moves inexorably to the next even-numbered year.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com