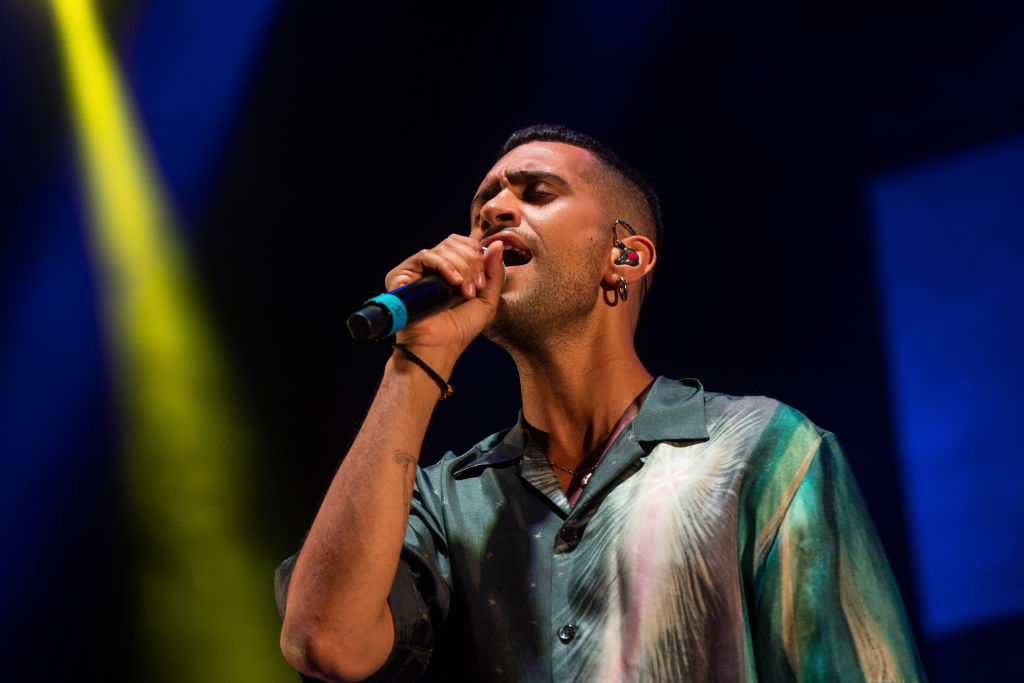

In February, Alberto Biancheri, the mayor of a small Italian coastal town near the French border, walked onstage carrying a statuette of a golden lion: the prize of the 2019 Sanremo Festival, awarded every year to the best new Italian song. TV cameras zoomed in on the winner’s shocked face, immediately sparking memes on social media. Mahmood, then 26, had pulled off a surprising upset and managed to conquer Italy’s most prestigious music competition with his song ‘Soldi’ (‘Money’). His victory quickly became a cultural turning point in Italy’s polarized climate around immigration, drawing scorn from Italy’s leading populist and far-right politicians, and catapulting Mahmood into the national spotlight.

Released on Feb. 6, after Mahmood’s first EP came out in late 2018, ‘Soldi’ was performed in public for the first time at Sanremo and instantly became a hit. ‘Soldi’ is not really about money. Written by Alessandro Mahmoud (stage name Mahmood), who was born in Milan to an Italian mother and Egyptian father, the song tells the story of Mahmood’s father’s absence during his childhood, after his parents separated when he was 5 years old. The lyrics describe a father who disappears and reappears as he pleases, smokes a hookah, drinks champagne during Ramadan and keeps asking: “come va?” (“how’s it going?”). “There’s quite a bit of anger in Soldi, it was a way to let off steam,” says Mahmood, speaking over the phone from Milan. It also includes a verse in Arabic: “waladi habibi ta’aleena” (my son, my love, come here), which recalls memories of his father calling him from the playground in a language he doesn’t speak himself.

Since its launch in 1951, the Sanremo Festival has become one of the country’s biggest televised events, with the winning song going on to represent Italy at the Eurovision Song Contest in May. That Soldi could win what is widely regarded as a traditional festival of Italian music, seemed to be a moment redefining “Italianess.” Mahmood agrees. “I’m very happy that people appreciated my style,” he says. “I think it was one of the more modern festivals in the past years, also thanks to other artists who brought a “new wave,” and breathed new life into Italian music.”

Not everyone saw it that way. The country’s leading politicians were among the first to express their dissatisfaction on social media, saying Mahmood’s victory — which was decided in part by music industry personalities and journalists— represented the division between ordinary Italians and the liberal elite.

Luigi di Maio, the leader of the anti-establishment Five Star Movement and then Deputy Prime Minister complained in a Facebook post that it represented the wishes of a jury made up of “journalists and the radical chic” rather than those of the voters at home. “Sanremo has shown to millions of Italians the abysmal distance that exists between the people and the ‘elite,’” he said. “Maybe next year the winner could be chosen only with the tele-voting, given that it costs Italians 51 cents, let’s make it count.”

Matteo Salvini, leader of the far-right League party who was recently ousted from government as Interior Minister, tweeted: “#Mahmood….mah….The most beautiful Italian song?!? I would have chosen #Ultimo, what do you say??” He later told Italian daily La Repubblica: “Sanremo is the mirror of Italy. There’s the jury and then there’s ordinary people: they are two worlds far apart. And the winners are victims of the system.”

So far, Mahmood has seemed unperturbed by the xenophobic rhetoric coming from politicians like Salvini, who implemented several anti-immigration policies while in office. “Of course, I don’t like the idea that my music may be used for a political cause,” he says. “But in the end, all this stuff about politics only lasted a while and Soldi has continued to travel a lot since Sanremo, and people are no longer talking about it in this way.”

And ‘Soldi’ has traveled unusually far for an Italian song. It has been streamed over 100 million times on Spotify since February, topped the charts in Italy and reached platinum status in Spain, Switzerland and Greece. It also made it to second place at the Eurovision Song Contest in Tel Aviv in May, and in June it became the most listened to Italian song in Spotify’s history. A European tour of his debut album, Gioventù Bruciata (“Wasted Youth”), has been announced for October, and tickets are selling out fast. Extra shows have been announced in London, Paris and Berlin.

Mahmood’s rise could be compared to that of Lil Nas X or Lizzo in the U.S. — artists who have managed to break down cultural barriers. His music resonates with many Italians who grew up in the suburbs with immigrant parents, often at odds between two cultures. As for ‘Soldi,’ its catchy, impassioned and personal lyrics are also very relatable. The story of being abandoned by a father, “could easily be the story of many other families,” Mahmood says.

Though Mahmood’s mother is Italian, she represents a different kind of migrant in Italy: those who left the country’s rural areas for the industrialized north. One of 13 children, she moved to Milan from Sardinia with her family at the age of 18. She met Mahmood’s father at the bar where she worked with her brothers and sisters.

“I listened to both Italian and Arab music growing up,” Mahmood says. “That Arab influence is very much present in my music and I really feel it when I’m writing.” But American hip hop also made an impression on him. One of the first albums he bought was The Score by the Fugees. He recently met Lauryn Hill when he was her opening act at her Italian show. “I was ecstatic. To me she’s mythical, she’s one of the biggest artists in the world. I listened to that album on repeat for months.”

That mix of influences has made Mahmood’s music difficult to categorize. It has been described as “rap”, “trap” and “pop,” but to settle any doubts, Mahmood came up with his own term: “Morocco pop.” “People wanted to put my music in a category at all costs, but I don’t really know what it is,” he says, “So that’s what I came up with.”

Like Mahmood, many emerging Italian artists, such as Italian-Tunisian rapper Ghali, come from the deprived outskirts of Milan. In an apparent tribute to this setting, Mahmood’s newest song released on Aug. 30 is titled ‘Barrio’ (Spanish for ‘neighborhood’) and mixes in some Latin American influences into his Arab-Italian mix, with a collaboration with Colombian pop star Lalo Ebratt.

Mahmood always sings in Italian, but has previously added Spanish lyrics to a version of Soldi by collaborating with a Spanish singer. As the role of English as pop’s lingua franca is changing, artists like Bad Bunny, Rosalía or BTS have found international success singing in their own languages. Mahmood hopes he can be part of this trend. “With this new wave of music in Spanish, people are a bit more open-minded regarding languages,” he says. “A few years ago it was limiting. If you didn’t sing in English people turned up their noses. But language has become something people are less fussy about. When people listen to music they are less prejudiced than they used to be.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Julia Webster at julia.webster@time.com