On Wednesday, as Americans along the East Coast warily watched the progress of Hurricane Dorian, observers across the country noted something else with alarm.

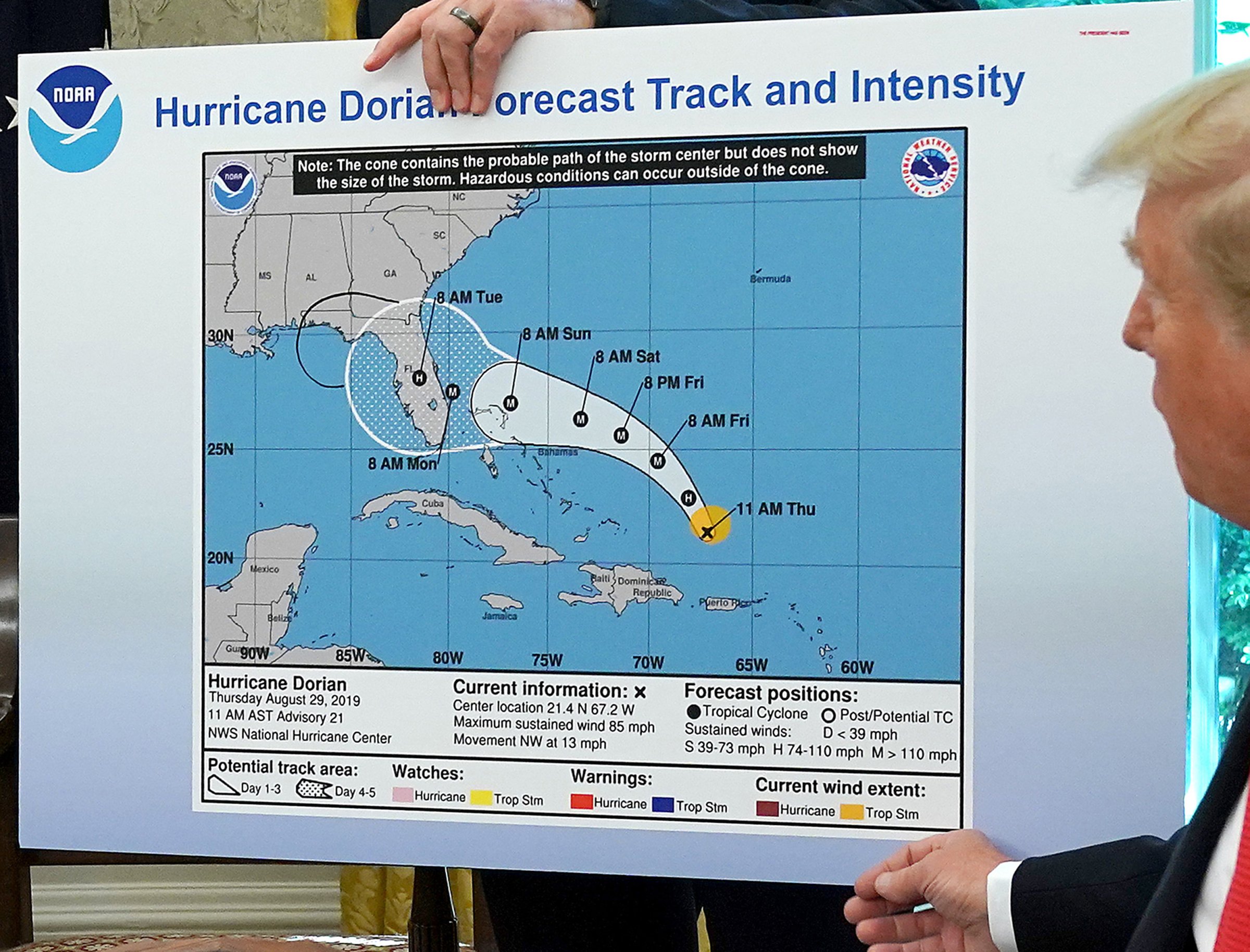

When President Trump held up a map of Hurricane Dorian’s projected path, it included a Sharpie-drawn extension to show the storm hitting Alabama — an apparent attempt to defend an incorrect tweet he posted on Sunday, which claimed that Alabama was one of the states in the path of the storm. In fact, the National Hurricane Center did not, at any point, include Alabama in its forecast for where Dorian would fall. (Alabama did appear on a map of the probability of tropical storm conditions, but with low likelihood of actually seeing those conditions, according to the Washington Post.)

As was quickly pointed out, it is against the law to publish a falsified official weather forecast:

“Whoever knowingly issues or publishes any counterfeit weather forecast or warning of weather conditions falsely representing such forecast or warning to have been issued or published by the Weather Bureau, United States Signal Service, or other branch of the Government service, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than ninety days, or both,” states the 1948 regulation on false weather reports. The current law applies to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Weather Service (NWS), the government agency that provides weather forecasts and reports across the country (formerly known as the Weather Bureau).

But why does such a law exist in the first place?

Officials at the turn of the 20th century likely did not predict this particular situation with President Trump when they drew up the law. But, though the current law dates to the 1940s, versions of this regulation go back more than a century, to a moment when meteorology was not yet an established science. In that atmosphere, the Weather Bureau sought to professionalize the practice and make sure its weather agencies could only be invoked alongside legitimate forecasts, explains Kristine C. Harper, a professor of history at Florida State University whose book, Weather by the Numbers: The Genesis of Modern Meteorology, looks at how meteorology took shape in the U.S. in the 20th century.

The 1905 appropriation bill for the Department of Agriculture, which oversaw the Weather Bureau at the time, outlawed false weather reports in legislation very similar to that on the books today. That law was likely part of an aim to prevent amateur weather forecasters from pretending they were a part of the government agency, Harper tells TIME. Back then, the challenges to “real” meteorology would have come mostly from farmers and fishermen — people whose vocations made them adept at reading the skies — who would try to sell their own weather forecasts, she says.

“The Weather Bureau was trying to protect its brand,” she says. “There were always people who claimed they could forecast the weather.”

Weather agencies saw a real shift during and after World War II, when the number of meteorologists in the U.S. bloomed from just a few hundred to thousands of trained forecasters. While they played an important role during the war, not all could be employed by the Weather Bureau at the war’s end. Many of the excess forecasters set up consulting firms that led to the independent weather agencies widely used today, including outlets like AccuWeather and The Weather Channel.

According to Harper, the Weather Bureau didn’t mind if people took on forecasting on their own — the real objection came when those people claimed their information came from the government. “They didn’t want some company providing reports to farmers, people with transportation interests or construction companies,” she says. “They didn’t want to be held responsible for weather reports they didn’t put out.”

Nowadays, the commercial opportunities in weather forecasting seem limitless as technology improves and climate change makes for more extreme events, and the rise of independent companies well-equipped to predict the weather has presented a new challenge to the National Weather Service. But, for now, the law still holds. And for good reason, Harper says. She notes that, by insisting Hurricane Dorian could affect Alabama, Trump — who continued to double down on his defense of his original tweet — could have caused real problems for the National Weather Service: for example, business owners there could have closed down in anticipation of the storm and later expected a financial reimbursement, she says.

“That’s why this law was put into effect,” she says. “It’s hurricane season. People have to be confident in what they’re looking at. It’s hard enough as it is to get people to do the right thing when the NWS is telling them what’s going on, much less if we have bad information going out to people.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Mahita Gajanan at mahita.gajanan@time.com