On the evening of Aug. 23, 8-year-old Jurnee Thompson was watching pre-season football games at Soldan High School in St. Louis with family members — her cousin and her two sisters — as a reward for her recent good behavior. She had just started the third grade.

When the games ended and people started to exit the school grounds, fights broke out, and police officers responded to the scene. As they arrived, several gunshots rang out. Four people, including Jurnee, were shot and taken to the hospital. Two 16-year-olds boys were listed in a serious but stable condition and a 64-year-old woman who was listed as stable. All three were later released.

Jurnee, though, was pronounced dead.

“She was like an old soul, she just loved her family,” Jurnee’s father tells TIME. “I just want to ask whoever did this, ‘why’d you take my baby away?'”

Jurnee is one of 13 children who have been killed as a result of gun violence in St. Louis since April, according to the St. Louis Police Department. Last year, only two kids were killed in the same time period, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported. The shootings have left the city in turmoil, according to residents and activists in the affected neighborhoods. While differences of opinion exist in how best to respond, a near universal belief is that change — whether legislative, sociocultural or community-driven — is overdue. And concern remains that the systemic violence, and its impact, is being overlooked as the U.S. focuses instead on responding to singular but frequent mass shootings.

Six of the victims in St. Louis were 10 years old and under, while another five were between the ages of 15 and 16, the St. Louis police department said. Two other incidents involve victims under the age of 17, but are currently being investigated as “suspicious sudden deaths” and not homicides. According to police, a suspicious sudden death is one where the circumstances cannot be explained as opposed to a homicide, which involves intent to kill.

All of the victims were African American.

Only one of the crimes has led to charges — on Aug. 29, police arrested 54-year-old Joseph Renick, a white male, in the shooting of 15-year-old Sentonio Cox, charging him with first-degree murder (as well as two additional felony charges of unlawful criminal action and the unlawful possession of a firearm), the police department said.

Although it is not clear how Sentonio and Renick’s paths crossed or what precipitated the shooting, according to the Associated Press, “a St. Louis police detective wrote in the arrest report that Sentonio was backing away from Renick with his hands raised when Renick shot him in the head.”

He is currently being held on a $500,000 bond. Renick’s attorney, Charles Barberio, tells TIME that his client will be pleading not guilty, and “vehemently denies” the allegations. Barberio adds that the police department’s probable cause statement cited by the AP is “deficient, legally” and that he does not believe there is any evidence to support the charges.

An arrest related to the death of 7-year-old Xavier Usanga, who was shot on Aug. 12 while playing in his backyard with his sisters, was also made on Aug. 28. A suspect, identified by police as Malik Ross, was arrested for an unrelated federal crime, and allegedly admitted to shooting Xavier during an interview with police.

Ross’s lawyers disputed this claim, and District Attorney Kimberly Gardner later announced that there was not enough evidence to charge Ross in Xavier’s death. “Based upon the current evidence and Missouri law, we are unable to determine who is legally responsible for the death of Xavier,” Gardner said in a statement posted on Twitter. “The alleged ‘confession’ of the identified suspect and others involved are not fully supported by the current physical and/or eye-witness evidence.”

While Ross remains in custody, his lawyer confirms to TIME that he has not yet been indicted on any other charges.

While impacting the city as a whole, the trauma has been particularly hard on other children in the neighborhoods in which the shootings have been concentrated, who have seen some of their classmates and neighbors killed. School districts have increased security measures in place at football games last weekend after the shooting in which Jurnee was killed, the St. Louis Dispatch reported. Students were also met by grief counselors when schools started back up, according to community members.

Missouri is among the top five U.S. states ranked by firearm mortality (21.5 deaths per 100,000 Missourians) according to the most recent CDC statistics. St. Louis — a city of just over 300,000 people — has seen 138 homicides in 2019, according to newly-released police data. Of the victims, 121 were listed as African American, and over 90% of the deaths came from incidents involving guns.

“We have people who do not value life, and have no problem taking a life,” James Clark, a community activist in St. Louis tells TIME. “We in the African American community can no longer ignore the fact that we shoot and kill each other everyday of the week. We’ve ignored it for too long. This crisis has gone undiscussed and unaddressed for years.”

Clark is the Executive Director of Better Family Life, an organization with the goal of establishing positive and innovative changes within St. Louis. Clark’s organization deploys outreach workers, many of them former gang members and drug dealers, to work with families and help deescalate conflicts in the community.

“We [community members and local politicians] have not put resources where they need to go, and now you have behavior in a community that has reached diabolical dimensions,” Clark says.

Zaki Baruti, the president of the Universal African Peoples Organization (UAPO) in St. Louis, lists a number of factors as contributing to the gun violence problem: a lack of economic opportunity, a struggling education system and all-too-easy access to weapons. “At some point this country needs to acknowledge the impact of gun violence in communities like ours,” Baruti tells TIME.

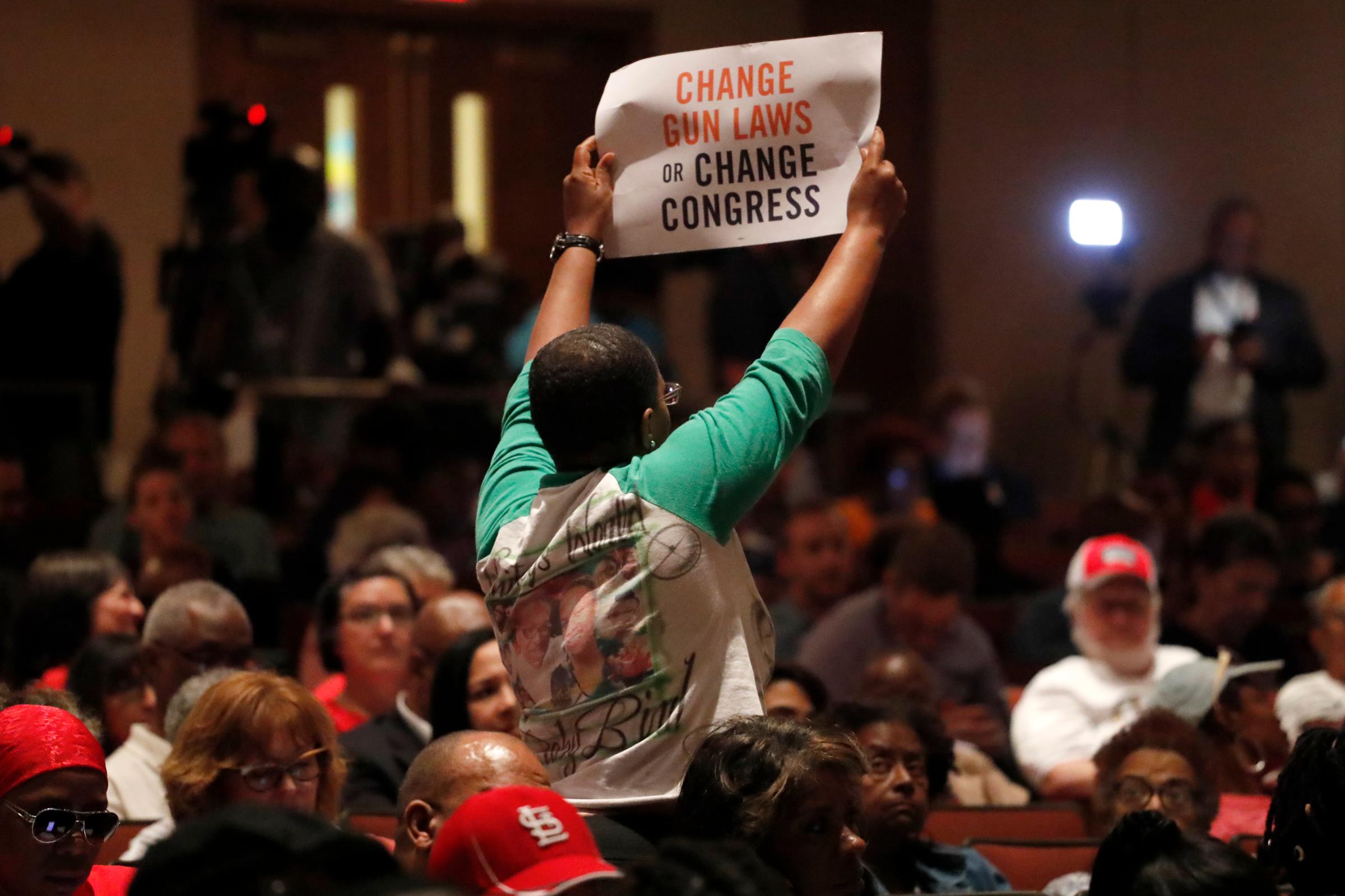

Last week, St. Louis came under a national spotlight as the grim death count — 13 children killed — spurred headlines and conversation. But in many respects, the mass shooting in Odessa, Texas that left seven people dead has eclipsed the story — and has left many fearful that the lack of continued attention will make it harder for the changes they are championing to be enacted and enforced.

“We don’t get the same attention that a mass shooting garners,” Clark says. “It’s not just St. Louis, you can look at any African-American community with this problem. I guarantee you if white boys were being killed at the rate that African-Americans were being killed, the broader community would intervene.”

St. Louis lawmakers have called for Missouri Gov. Mike Parson to hold an emergency session on gun violence, but he has elected not to. “[A] special session is not the correct avenue,” Parson said in a statement on August 27, via the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “If we are to change violent criminal acts in Missouri, it will take all of us at the federal, state, local, and community levels working together toward that common goal.”

Parson’s office did not immediately respond to TIME’s request for comment.

On Aug. 24, the day after Jurnee was shot, St. Louis Mayor Lyda Krewson announced rewards of up to $25,000 for anyone who provides information on her death. (The reward is also being offered with regards to the killings of four other children who died by gun violence in the city in recent months: Xavier Usanga, Kayden Johnson, Kennedi Powell and Eddie Hill.)

A deadline for those wanting to claim a reward was originally set for Sept. 1, but has since been extended to Sept. 10. The St. Louis Police Department tells TIME they have received an increase in tips in recent days, but will not discuss any information they have received while their investigations are ongoing.

“Conventional policing tactics are not enough. We need information from the public to help us bring these shooters to justice,” Krewson said at a press conference. She has also argued that St Louis should be allowed to amend Missouri’s concealed carry laws, and require gun owners in the city to receive a permit before arming themselves with a concealed weapon.

Clark believes that law enforcement does all that it can, and that the changes in the affected communities must come from the people who inhabit them. “It starts in the family and it starts in the neighborhood.” Clark says. “Putting it on law enforcement is scapegoating. We’ve got to take the focus off of law enforcement as the solution to crime and violence.”

Other activists, however, have a different perspective. John Chasnoff, co-chair of the Coalition Against Police Crimes and Repression, a St. Louis-based organization, says that the city’s current model of police work is not proving to be effective. “Every police chief says that we cannot arrest our way out of this problem, but they keep trying to arrest their way out of the problem,” Chasnoff tells TIME. “We think that’s the wrong approach to dealing with violent crimes and high crime rates.”

Like Clark and Baruti, Chasnoff says that what would really work toward keeping people — and young people in particular — safe is an increased focus on jobs, healthcare and homes in communities that deal with crime. He believes that some of budget that is used for jails and what he believes amounts to over-policing could instead be used to address the more economic issues that plague the city.

“No matter how many arrests you make, you need healthy communities in order to stop these types of crimes,” Chasnoff says.

The idea of being labelled a “snitch” for cooperating with the police is also widely seen as in issue. St. Louis police chief John Hayden described potential witnesses in many cases as being “less than fully cooperative with our investigators” in a July interview with the AP.

“There is a fear of being killed if you talk to the police,” Clark added.

Along with that fear of retaliation, people in the neighborhood simply do no trust the police, Baruti says. “What happened in Ferguson is still on a lot of people’s minds.”

It’s been five years since the state of Missouri was thrust into national spotlight after 18-year-old Michael Brown Jr. was shot and killed by officer Darren Wilson. Brown, who was unarmed, was shot six times by the officer. The incident sparked protests not only in Ferguson, which is about 10 miles from St. Louis, but also across the country. The shooting and ensuing protests lead to widespread discussions on the unarmed shooting of black men and women by police.

Baruti says that people need to get past the fear of “snitching” or not trusting the police. “If they know [something], they need to come forward,” Baruti says.

“People have to put themselves in the shoes of the [victim’s] family,” Clark adds. “If someone killed a member of your family, you would want someone to come forward.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Josiah Bates at josiah.bates@time.com