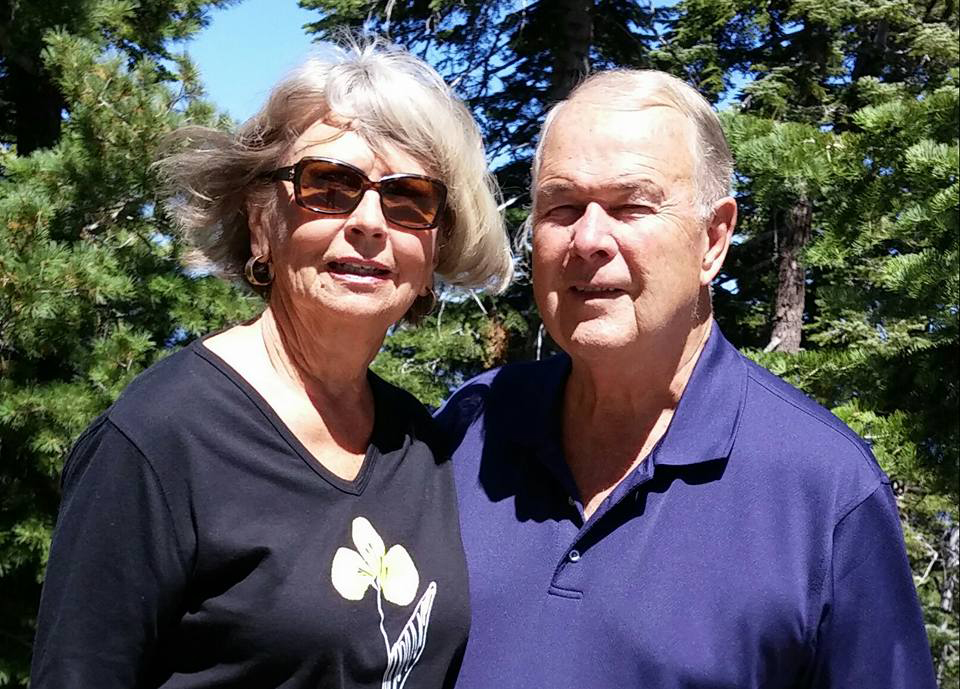

Mary Knowlton was 73 years old when she was shot to death by a police officer demonstrating to civilians the perils of his job. The officer, Lee Coel, was playing the “bad guy,” and Knowlton was randomly selected to play a cop during the exercise in Punta Gorda, Fla. back in 2016. Instead of firing blanks as the retired librarian approached him, Coel shot her with two live bullets. The shooting was captured on video, which shows Knowlton spinning around, slumped over and grabbing her stomach, before collapsing in front of a stunned crowd that included her husband of 55 years.

“She goes down and no one knows if she’s pretending,” says one of her two sons, Steve Knowlton, 53. “Then they flipped her over.”

As panicked authorities rushed to help Knowlton and usher away the 30 other civilians who were watching the exercise, Knowlton bled out from her abdomen and left elbow in the Punta Gorda Police Department’s parking lot. She died about an hour later at a hospital. “It just feels like our souls got ripped out of our chest,” her son says. “This is the kind of thing some people don’t come back from.”

August marks the three-year anniversary of Knowlton’s death, but Coel, 31, has yet to stand trial on a manslaughter charge and is free on bond. He remained on the job for seven months after the shooting and was not fired until the state attorney filed charges—something his defense attorney, Thomas Sclafani, says should never have happened. “This case should not have even been prosecuted,” says Sclafani. “It’s a tragic accident. That’s all it is.” Sclafani has twice filed motions seeking to move Coel’s trial out of the county, which he says was necessary to find jurors who are not extremely familiar with the case and one reason it’s moving slowly. In June, Coel’s trial was rescheduled for at least the third time, to Oct. 15.

“I haven’t given up hope,” Steve Knowlton says, “but I don’t think we’re going to get justice.”

History suggests he’s right. Since Eric Garner died five years ago while being wrestled to the ground by a New York City police officer in a case that sparked national outrage, few instances of civilian deaths at police hands, either accidental or intentional, have ended with cops facing trial. According to Mapping Police Violence—one of the few groups that tracks deadly police encounters in the absence of a comprehensive national database—law enforcement officers in the U.S. intentionally or accidentally killed more than 6,800 civilians between 2013 and 2018. Other groups and media that track data report similar figures. In 2017 and 2018, KilledbyPolice.net said more than 2,300 people were shot and killed by police, and the Washington Post recorded 1,978 instances in the same two-year period. Among deaths reported by Mapping Police Violence, an officer was charged with a crime in 1.7% of the cases, says Samuel Sinyangwe, a policy analyst who co-founded the on-line non-profit site, which compiles data from news articles, police reports, social media and other sources.

Federal prosecutors on Tuesday announced they would not bring civil rights charges against Daniel Pantaleo, the white officer who held Garner down in July 2014 as the 43-year-old father of six repeatedly gasped “I can’t breathe.” While calling Garner’s death a tragedy, the U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District, Richard P. Donoghue, said the evidence “does not establish beyond a reasonable doubt that Officer Pantaleo acted in willful violation of federal law.” A grand jury had also previously declined to indict Pantaleo. In May, the officer faced an internal NYPD disciplinary trial before an administrative judge who has not yet delivered a verdict to the police commissioner. Pantaleo continues to collect his salary of $98,000 on desk duty. “Eric is crying from heaven,” Garner’s mother, Gwen Carr, said at a news conference at the start of the trial.

What the Knowltons are going through is very different from what Garner’s family has gone through, and what the families of scores of mostly black and Hispanic men and boys killed in use-of-force incidents involving police have experienced. The Knowltons know their loved one wasn’t targeted because of race—Mary Knowlton was white, as is the officer—and she was not assumed to be committing a crime. Her sons didn’t grow up with the wariness toward law enforcement shared by many young men of color, which Steve Knowlton, a realtor in Cocoa Beach, Fla., acknowledges. “This is far beyond anything I could ever imagine could happen to us,” he says. But after all this time, they share something with those other families: the loss of faith in a system that is supposed to protect them.

For most of the last three years, Steve Knowlton has been driven by the need to secure justice for his mother, who taught her children never to harbor hate. “I started becoming this person who was on a mission,” he says. But now the task is taking its toll.

“I don’t know if I can make this my life, my cause,” he says. “It’s killing me.”

***

While it’s rare to see officers indicted for killing civilians, convictions are rarer. Of the 104 state and local law enforcement officers who have been arrested for murder or manslaughter for fatal on-duty shootings since 2005, 36 have been convicted of a crime, according to criminologist Philip Stinson, who was a police officer in New Hampshire in the 1980s. By comparison, of the 217 people charged with murder and manslaughter in the nation’s 75 largest counties in May 2009 alone, 70% were convicted of murder or other felonies, according to the most recent data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Even when officers are convicted, they’re often found guilty of lesser offenses and receive more lenient sentences than civilians convicted of the same crimes, according to researchers. “There’s clearly bias there in the system,” says Sinyangwe.

Lawyers involved in prosecuting police say there are several factors at play in these cases, including the powerful unions that often represent police officers and discourage elected district attorneys from pursuing charges. It’s also difficult for many civilians to see police as anything but good guys. “Oftentimes, because you have enough people in society who have such a favorable opinion of the police, you end up in a situation where one of those people almost always makes it onto a jury,” Sinyangwe says.

Jurors may also be reluctant to question the split-second decisions police officers must make during life-or-death moments in an unquestionably dangerous line of work. More than 1,500 law enforcement officers have died on the job in the past decade, and tens of thousands more have been injured, according to the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund and the FBI. In 2018, the FBI says, 55 officers were gunned down or run over while making arrests, responding to disturbance calls and conducting investigations and traffic violation stops. That was nine more than in the previous year.

The idea of convicting an officer for a mistake made in the heat of the moment—or while conducting what was supposed to be a friendly exercise with civilians—is especially difficult for people who’ve been brought up to see police as their friends. Mary Knowlton was one such person. Days before she died, Knowlton told her family she wanted to attend the event to support her local police after a particularly perilous summer for law enforcement: in 2016, eight Baton Rouge and Dallas officers had been murdered in attacks amid a string of fatal police shootings of black men.

“We are on combat every day, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, against an enemy we don’t know,” says Thomas Lake, who was a St. Louis police sergeant in November 2016 when he was shot twice in the face while on patrol. Lake was in his marked patrol car at a traffic light when another driver pulled up next to him, whipped out a gun and opened fire without saying a word. “I registered it was a gun after he pulled the trigger and hit me in the face,” Lake says. “My situation happened in less than a fraction of a second, and it changed my life forever.”

Studies show that in the U.S., white people are far more likely to trust law enforcement officers than people of other races. While 42% of white adults said they have a lot of confidence in their local police, only 14% of black adults shared that same confidence, likely due to the spate of deadly encounters between law enforcement officers and minorities, a Pew Research Center study found in 2016. But since Garner’s death brought a surge of momentum to the Black Lives Matter movement, this distrust is proving to be formidable. In St. Louis County, Missouri last year, longtime prosecutor Bob McCulloch lost his re-election bid in a major upset traced to his office’s failure to prosecute the officer who’d killed Ferguson, Missouri teenager Michael Brown.

***

Under use-of-force standards set by at least two U.S. Supreme Court cases in the 1980s, police officers may be justified in using lethal force when they have reason to believe there is a credible and immediate threat to themselves or others. That threshold, critics say, makes it hard to prosecute officers or even challenge them. “It’s a free get-out-of-jail pass from the highest court in America,” says attorney Ben Crump, who has represented several families in high-profile cases involving police use-of-force, including the family of Michael Brown.

Because there’s no federal requirement that officers working for the country’s 18,000 law enforcement agencies first exhaust other resources before using lethal force, advocates for police reform say there’s no incentive for them to change their ways. “Police behaviors have been very, very slow to change,” says Stinson, the criminologist. “It’s like trying to turn an aircraft carrier around on a dime.”

It’s especially difficult to expect change when the job risks remain so high, says Lake, 49, who says the trauma of his shooting forced him to retire early after 22 years as a police officer. “When your life is based on a split-second decision, everyone can Monday morning quarterback you,” he says. “But until you’re the person in that position and you’ve seen the things that that officer has seen, you don’t know that you wouldn’t make the same decision.”

While states can set use-of-force laws that are stricter than the current standards, most have not. A 2015 Amnesty International USA report found nine states and Washington, D.C. had no such laws in place, while 13 had laws more lax than the standards. The human rights group said none of the 50 states complies with international law that says officers can only use deadly force as a last resort to protect themselves and others from death or serious injury. States that have tried to pass stronger laws matching the global standard have faced intense uphill battles.

In February, when California legislators introduced a bill that would have been the first in the nation to allow officers to use deadly force only when there is “no reasonable alternative,” dozens of police unions opposed it. The unions argued the bill would criminalize public safety, discourage proactive policing and embolden criminals. It was proposed after protests erupted over the police killing of Stephon Clark, a 22-year-old unarmed black man who was shot seven times in his grandmother’s backyard in 2018 by police investigating a vandalism complaint.

Among the bill’s proponents was Laura Serna, whose father, 73-year-old Francisco Serna, was shot dead by police who mistook the wooden crucifix he was holding for a weapon. Francisco Serna, who suffered from dementia, was outside his Bakersfield, Calif. home shortly after midnight on Dec. 12, 2016 when police—responding to a neighbor’s call of an older Hispanic man with a gun—shot him five times. At a news conference, Bakersfield Police Chief Lyle Martin said the shooting was justified because Francisco Serna had ignored officers’ commands to stop walking and to remove his hand from his jacket. “A person with dementia with a gun can kill you just like a person without dementia with a gun could kill you,” Martin said. The district attorney agreed. “It was another punch to the stomach,” says Laura Serna, a 50-year-old social worker. “They had just gotten away with murder.”

By the time a revised version of the California legislation passed the State Assembly at the end of May and the State Senate in July, it had lost some of its strongest language. If approved by Governor Gavin Newsom, who has indicated his support, the bipartisan legislation would require officers to use deadly force only when “necessary” and not just when they believe there is a reasonable fear. But it no longer requires officers to exhaust all other reasonable alternatives or try to first de-escalate confrontations. “They watered down the bill a lot from what we wanted,” says Crump, the civil rights attorney, who represents Clark’s family. “I’m still cautiously optimistic that it gives us hope for change.”

Laura Serna agrees. “This is the beginning of change,” says Serna, who joined a coalition of activists fighting for police reform after her father’s death. “It would set a pattern for the rest of the country.”

***

When it comes to incidents like the one that killed Mary Knowlton, though, there are no clear precedents or rules for families to turn to for guidance. In 1984, a jury in California acquitted an officer who shot and killed a 22-year-old woman as she fled from the bank robber who’d been holding her hostage. After nearly five years of trying to pursue a wrongful death suit against the city of Escondido, outside San Diego, the family of the woman, Leslie Landersman, gave up. “I was hoping to see some justice, but it became apparent that there wasn’t ever going to be any, and I was told by some judges that I would never feel satisfied, even if it did get to court,” her widower, Mark Landersman, said at the time. Thirty years later, a family on the other side of the country found itself facing a similar tragedy when a police officer shot dead Andrea Rebello, a 21-year-old Hofstra University student, while responding to a home invasion at her off-campus house in Uniondale, N.Y. Her family said police acted recklessly by firing at the intruder as he held Rebello in a headlock, but the officer was not charged.

In September, however, jurors will begin hearing the case of former Dallas police officer Amber Guyger, who’s charged with murdering Botham Jean, an unarmed black man, in his own apartment. Guyger, who is white, says she accidentally walked into the 26-year-old’s apartment instead of her own after work one night and opened fire, thinking there was an intruder in her home. And in a rare conviction—believed to be the first of its kind in decades in Minnesota—a jury in April found Minneapolis police officer Mohamed Noor guilty of murder after he fatally shot Justine Ruszczyk Damond, a 40-year-old woman who had called 911 to report a possible rape and who was unarmed when she approached Noor and his partner in their police car. Noor was the third police officer in the last year to be found guilty of murder for fatal on-duty shootings in the U.S. following the convictions of Roy D. Oliver II in Balch Springs, Texas and Jason Van Dyke in Chicago.

“Policemen are no better than any other citizen. They should be held accountable like any other citizen,” says Lake, the retired St. Louis police sergeant who was shot on-duty. But Lake adds that the circumstances surrounding police on trial often are unique from those involving civilians. “What makes policemen different,” he says, “is they’re carrying different baggage—the experiences of meeting dangerous people and the burdens of carrying everyone else’s problems.”

Though the circumstances in Knowlton’s case are unusual, her death has been described as an accident—as is often the defense in civilian deaths—rather than the result of carelessness. “It’s not a criminal case,” says Sclafani, Coel’s defense attorney. The idea for the role-play exercise came from watching other departments conduct it on YouTube, the Punta Gorda Police Department’s operations commander told investigators from the Florida Department of Law Enforcement. The deadly mix-up happened when Coel—who stored boxes of both live ammo and of blank cartridges in the back of his patrol car—reached for the wrong box and loaded his revolver with what he thought were blank firing cartridges, investigators said. Coel’s “inability to differentiate” between the two types of ammunition, which are similar in shape and size, led to Knowlton’s death, the state investigation found.

In the months after the shooting, Steve, his 56-year-old brother William and their father assumed law enforcement would investigate what had gone wrong and hold accountable those responsible for the mistake. When the city offered the family a $2 million settlement, they took it instead of filing a civil lawsuit. But as time went on, the family says it felt ostracized for demanding justice. When Tom Lewis, the Punta Gorda Police Chief at the time, faced a misdemeanor negligence charge as a result of the shooting, local businesses raised money for his legal defense. Uniformed officers packed the courtroom during his trial, which ended in acquittal after his attorney argued that Lewis had no way of knowing Knowlton could be harmed during the exercise. “You’re not only the victim, but you’re the bad guy,” Steve Knowlton says.

“Our family has to sit here as it drags on,” adds his brother, William. “The way that she got taken away,” he says, before trailing off. “The moment I’m a happy person is the moment I forget what happened to her.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com