Tommy Thompson served as U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services from 2001-2005 and as the 42nd Governor of Wisconsin from 1987-2001.

The President’s Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) just released a new report on how to beat back America’s opioid crisis. The CEA highlighted as potential solutions measures like curbing illicit drug trafficking, reducing over-prescribing in doctors’ offices, and cracking down on drug distributors fueling the epidemic for profit.

Those are noble goals, to be sure. But the CEA report lacks one crucial element in fighting this crisis: nurse practitioners.

About 72,000 Americans died from a drug overdose last year, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Over two-thirds of those deaths were from opioids. To put that in perspective, drug overdoses killed almost the same number of Americans last year as car crashes and guns—combined.

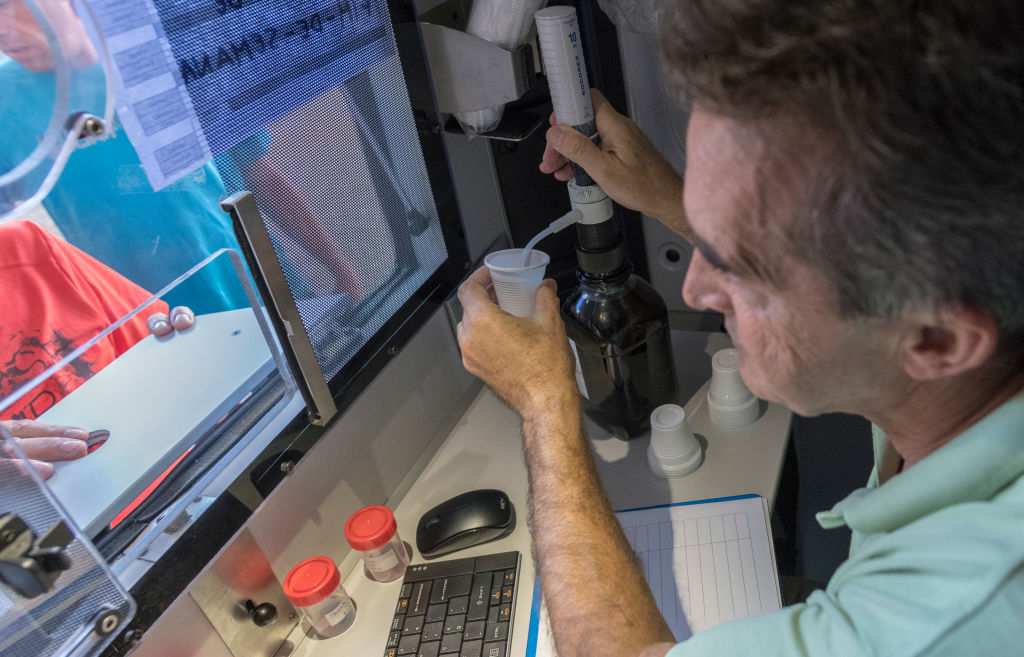

Primary care professionals are on the front lines of the opioid epidemic. And thanks to advances in “Medication-Assisted Treatment”—which combines medications that temper cravings, like methadone and buprenorphine, with counseling and therapy—they’re better equipped to treat dependence than ever before.

But the U.S. is suffering from a severe shortage of primary care professionals; a whopping 80 million Americans lack adequate access to primary care. The shortage is particularly bad in rural areas, where patients are “almost five times as likely to live in a county with a primary care physician shortage compared to urban and suburban residents,” according to a 2018 UnitedHealth Group report.

This presents a serious problem for those seeking substance-abuse treatment. Without access to primary care professionals, addicted patients struggle to receive the care they need. Right now, nearly 80% of Americans addicted to opioids aren’t receiving treatment.

Empowering nurse practitioners to treat addiction—and removing unnecessary restrictions at the state level—can go a long way in liberating American patients.

Nurse practitioners, or NPs, are well positioned to help patients get the care they deserve. Equipped with graduate degrees and advanced clinical training, NPs are qualified to assess patients, order and interpret diagnostic tests, develop treatment plans, and prescribe medications in all 50 states.

Studies have shown that NPs provide care that’s just as good as—and sometimes better than—physicians. According to a recent study in the journal Medical Care, Medicare beneficiaries treated by NPs had lower rates of preventable hospital admissions, hospital readmissions, and inappropriate emergency-room visits than those treated by physicians.

Between 2016 and 2030, the number of NPs in the workforce is projected to grow by 6.8% annually, according to a study from Peter Buerhaus a healthcare economist and professor of nursing at Montana State University. The report also found that these NPs will be far more likely to practice in rural and underserved regions,

But dozens of states unnecessarily limit where and how NPs can practice.

For instance, many states require NPs to sign elaborate “collaborative agreements” with physicians. These agreements reduce primary care options by limiting how and where NPs can practice. Some states will subject NPs to career-long supervision, delegation, and management—all to enable NPs to perform activities for which they are already well-trained.

Collaborative agreements can also thwart efforts to offer care in rural areas. Some states, like Mississippi, require NPs to practice within a certain number of miles of their collaborating physician. In addition, these agreements sometimes disrupt patient care. In Missouri, NPs can only prescribe limited quantities—and certain types—of medications.

Further, while NPs in 28 states can complete training and receive a waiver to prescribe Medication-Assisted Treatment, they can only utilize it if their collaborating physician is also qualified to apply for one.

In many cases, NPs have found it difficult to identify a physician who meets one or more of the required criteria—such as having addiction certification from the American Society of Addiction Medicine or having served as an investigator on an approved narcotic’s clinical trial—to be a “qualifying physician.” This ultimately restricts their patients’ access to critical addiction treatments.

These restrictions don’t just impact Medication-Assisted Treatment prescribing, they deter NPs from practicing at all. In fact, states with laws that limit NPs’ scope of practice have 40% fewer NPs per capita than states without. That’s why they make so little sense—particularly in states where the opioid epidemic is especially dire.

Federal lawmakers have demonstrated that they’re serious about ending the opioid epidemic. State lawmakers can show they’re serious by allowing NPs to do their jobs.

Correction: A previous version of this article implied that Peter Buerhaus worked for the D.C.-based conservative think tank American Enterprise Institute (AEI). In fact, Buerhaus was (and still is) affiliated with Montana State University, and was a contributor to a report published by AEI.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com