It has been a year since teachers began walking out en masse to protest the state of public education in the U.S. But in many of the states that saw significant activism from teachers in the past year, educators say they’re still fighting for the same changes.

A statewide strike in West Virginia in early 2018 helped to inspire similar action in Oklahoma, Kentucky, Arizona and Colorado, where teachers called for pay raises, smaller class sizes and more classroom funding. The movement has continued this year with one-day rallies in North and South Carolina last week and with strikes in several major cities, including Los Angeles, Oakland and Denver.

In spite of the gains made in several states and school districts during the past year, many teachers say they’re still fighting for more significant progress on the same issues.

“People treat West Virginia teachers—it’s really weird—almost like rock stars,” says Jenny Craig, a special education teacher at Wheeling Middle School in Wheeling, W.V., who has been a leader of teacher activism in the state.

“It’s so crazy because I feel like, yes, we made gains,” she adds. “But because we’re constantly playing defense, I feel like we don’t have time to really celebrate those moments.”

Ahead of National Teacher Day on Tuesday, Craig and teachers in other states around the country shared some of the biggest challenges their profession is still facing today. Their answers have been edited and condensed for clarity.

North Carolina: ‘The lack of respect’

Teachers in North Carolina marched on the state capitol in Raleigh on May 1, forcing many schools to close for the day. Educators called for more counselors, social workers and nurses in schools, pay raises for teachers, a $15 minimum wage for all school personnel and the restoration of additional pay for teachers with advanced degrees.

Tamika Walker Kelly, a music teacher at Morganton Road Elementary School in Fayetteville, N.C., was among the teachers protesting in Raleigh. She has been teaching for 12 years:

One of the biggest challenges that we face today is the lack of respect for the education profession, in particular with public education. We are the one area that services all kids regardless of where they come from. And because we are public and free for all, it has been a challenge for people to see how great our needs are. Public schools are a reflection of the society we live in, so if we want to see good outcomes in our society, in our children as whole human beings, we should invest in our public education. I see and feel a solidarity from other educators in other states because our issues are not that different. We are trying to defend and transform public education.

South Carolina: ‘People don’t want to go into this profession’

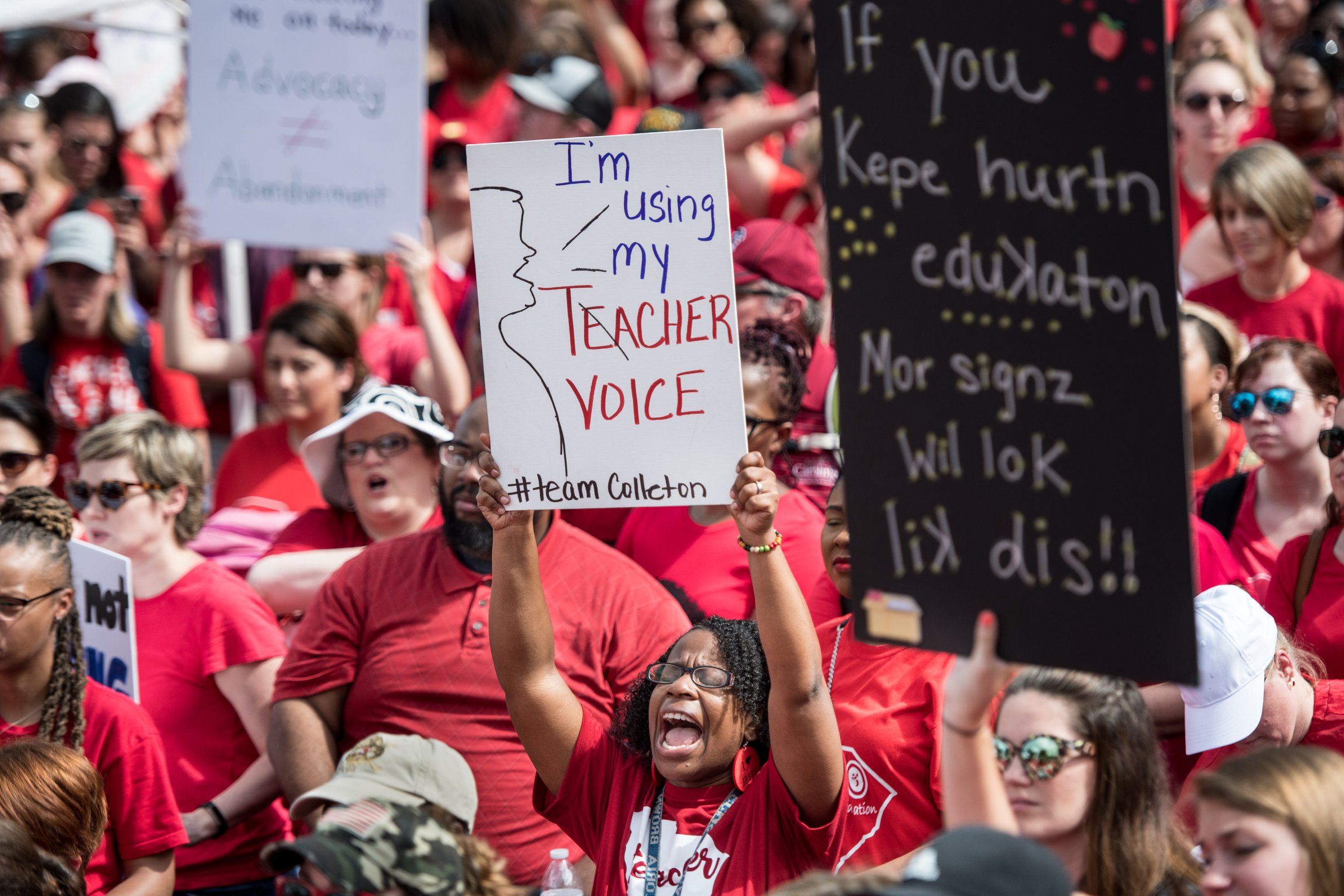

An estimated 10,000 teachers protested in Columbia, S.C., on May 1, making it one of the largest labor actions in the history of the state. Teachers demanded better pay, smaller class sizes, less testing and limits to the expansion of charter schools.

Teachers could get a 4% raise under next year’s state budget — a bigger pay hike than they’ve seen in years. But teachers are still calling for a 10% raise in order to recruit new teachers and retain veteran educators in a state where the minimum starting salary for teachers is $32,000 and the average salary was $50,395 this year, according to the National Education Association.

Keitt Easterling—who teaches students in the gifted and talented program at three schools in South Carolina’s Georgetown County School District—led an effort to get teachers from her district to participate in the protest on May 1. Easterling, who has been teaching for 25 years, donned a red wig in addition to her #RedForEd shirt while rallying outside the state capitol:

We have so many teachers leaving the profession, especially our young teachers. My grandmother was a principal and teacher. My mother was a principal and teacher. All my sisters are teachers. My 26-year-old son carried on the tradition and was an early childhood education major, but he does not want to teach here because he knows what the conditions are. That’s kind of heartbreaking for me. I want things to be better. I would love for teaching to go back to being less stressful, and I think all of that could also be helped if we had the support of our government, and we had better pay and smaller class sizes. All of that stuff would make teaching a more desirable profession for our young people again. We don’t have the numbers going into education in colleges like we used to. We have a huge shortage getting ready to hit us. People don’t want to go into this profession. That’s tough because it’s a profession that I really love.

West Virginia: ‘We are severely underfunded to meet mental health needs’

West Virginia teachers and other state employees won a 5% pay raise in 2018 after their nine-day strike. This year, teachers organized another walkout to fight a controversial education bill that would have established the first charter schools in the state. Educators who opposed the bill argued it would have shifted funding from traditional public schools toward charter schools, which are publicly funded but privately managed. The bill’s proponents argued it would provide families with more education options. Lawmakers postponed the bill indefinitely.

Craig, the West Virginia special education teacher and president of the Ohio County Education Association, helped lead the statewide walkout in 2018 and the two-day walkout this year. She has been teaching for 11 years:

We’ve been continually pushing for more mental health care in our schools for our students. We are severely underfunded and understaffed to meet our kids’ mental health needs. We have one of the highest rates of childhood poverty and childhood trauma. Our foster care system is just bursting at the seams. School has really become the panacea for everything. We are the hubs of our communities. Our kids don’t just come for academic instruction, but for social and emotional and behavioral support. We provide our kids with clothes, food and medical care. Here at my middle school, there’s a shower schedule. It’s very confidential, but they are able to come and shower as often as they want. We also have washers and dryers, and we’ll wash their clothes. We have one school counselor, and she is continually bogged down and busy. We have one mental health professional in the entire county. It’s an absolutely critical service. We are so severely understaffed to meet our kids’ mental and emotional health needs, and before you address that, you really can’t talk about school reform.

Oklahoma: ‘Teacher pay is better, but it’s still not competitive’

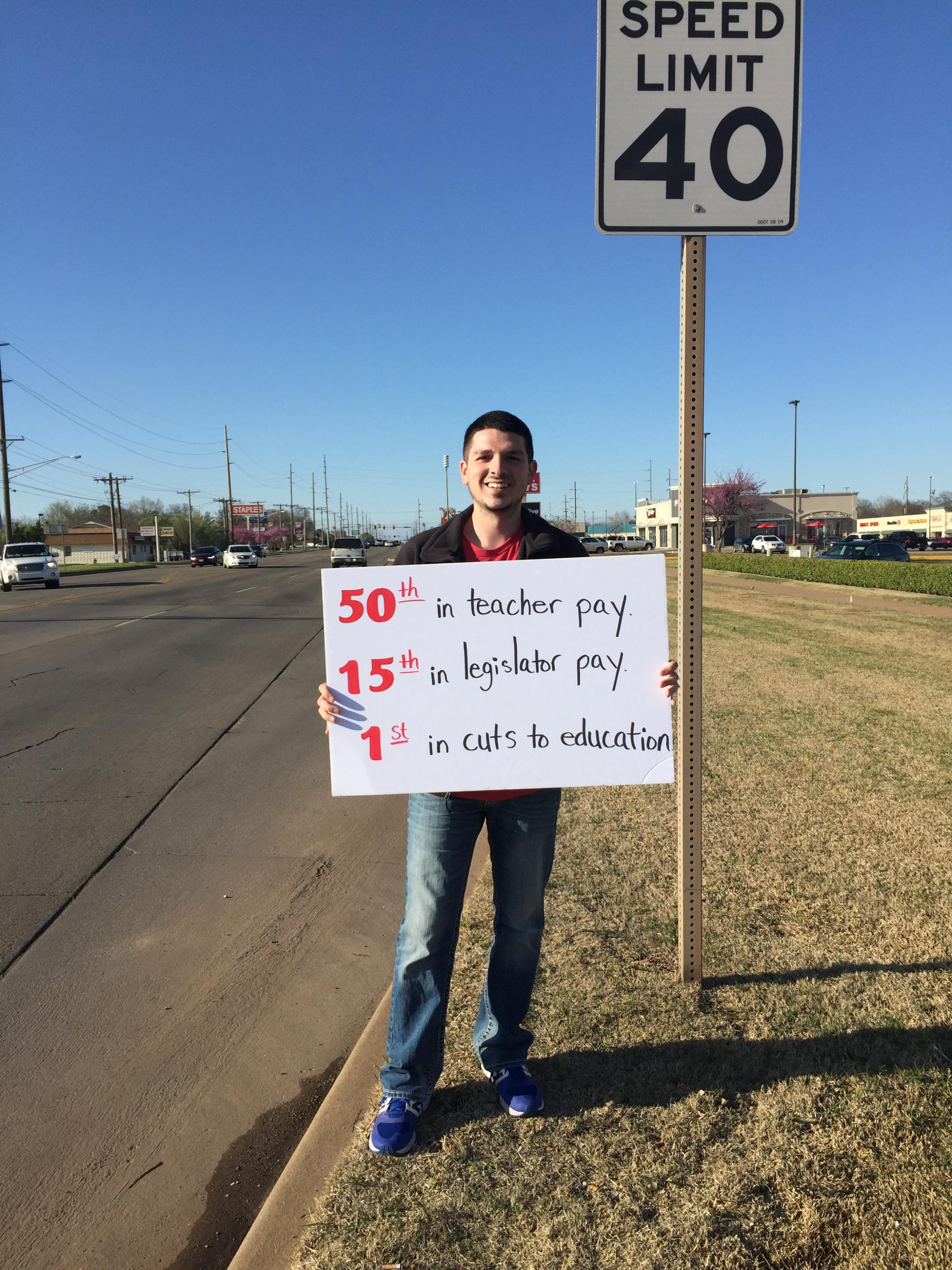

Oklahoma teachers last year won millions in new education funding, but the achievement fell short of their demand for a $10,000 raise for teachers and a $5,000 raise for support professionals, in addition to more classroom funding. Instead, state lawmakers passed an average pay raise of $6,100 for teachers and $1,250 for school professionals, funded by the first major tax hike in the state in nearly 30 years.

The pay boost increased the average teacher salary in the state from $46,300 in 2017-18 to $52,412 this school year. While the state also boosted per-student funding, education budget cuts had been so deep in the prior decade that per-student funding is still 15% below pre-recession levels, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Overall, teachers in the U.S. were paid 21.4% less than comparably educated professionals in 2018, according to the Economic Policy Institute, which described the gap as a “record high.”

Alberto Morejon, an 8th grade U.S. history teacher at Stillwater Junior High School in Oklahoma, was one of the leaders of teacher protests in the state last year. He has been teaching for four years:

It’s still the exact same struggles that, leading up to the walkout, we had last year. The teacher pay is better, but it’s still not competitive with our surrounding regions. We need more money added to the funding formula to help lower class sizes and pay for things like textbooks and supplies. It’s pretty much the exact same struggles. It’s just crazy to think about. And as all of this continues to go on, teachers continue to leave. We continue to get more emergency-certified teachers. I support teacher pay raises, but I would rather see money go to the funding formula because at the end of the day, you need both. Teacher pay does need to be more competitive. But we also need to lower classroom sizes. At the end of the day, you really need both of them. For the past 10 years in Oklahoma, lawmakers have neglected both.

Arizona: ‘Nothing has changed for our students’

After Arizona teachers walked out in April 2018, Gov. Doug Ducey promised to give them a 20% raise over three years. But like Oklahoma, Arizona is still well below pre-recession levels of per-student funding, and teachers are continuing to fight for more.

Rebecca Garelli, who teaches 6th grade science at Sevilla West Elementary School in Phoenix, is a lead organizer for Arizona Educators United. She has been teaching for 15 years:

While we did receive a small pay increase, our students received nothing from the legislature. We’re still looking at a serious funding deficit. Nothing has changed for our students. Our average class size is one of the largest in the nation. Our student-to-counselor ratio is the largest in the nation. And the money we spend per pupil is at the bottom of the barrel. Arizona still sits at the bottom of every single education statistic, including teacher pay. Our students are not better off than a year ago. I still have textbooks from 2004 and science materials that say, ‘Please use before November of 2007.’ Our classrooms are still suffering. I have 33 kids in five different classes I teach, and you’re incapable of building the desperately needed relationships with students to increase student achievement. We’re literally working to change the working conditions and learning conditions inside of the classroom. That’s our goal.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Katie Reilly at Katie.Reilly@time.com