With nearly 250 years of American history accounted for, it’s perhaps no surprise that the nation’s political life has had its good and bad moments. Political scandals have dogged Washington from the beginning, and continue to this day — a fact of which the nation was reminded on Thursday by the release of special counsel Robert Mueller’s redacted report on the Russia scandal.

It’s too soon to conclude where the Mueller report and surrounding saga will fit in the history of American political scandal, but other moments have firmly solidified their places in that past.

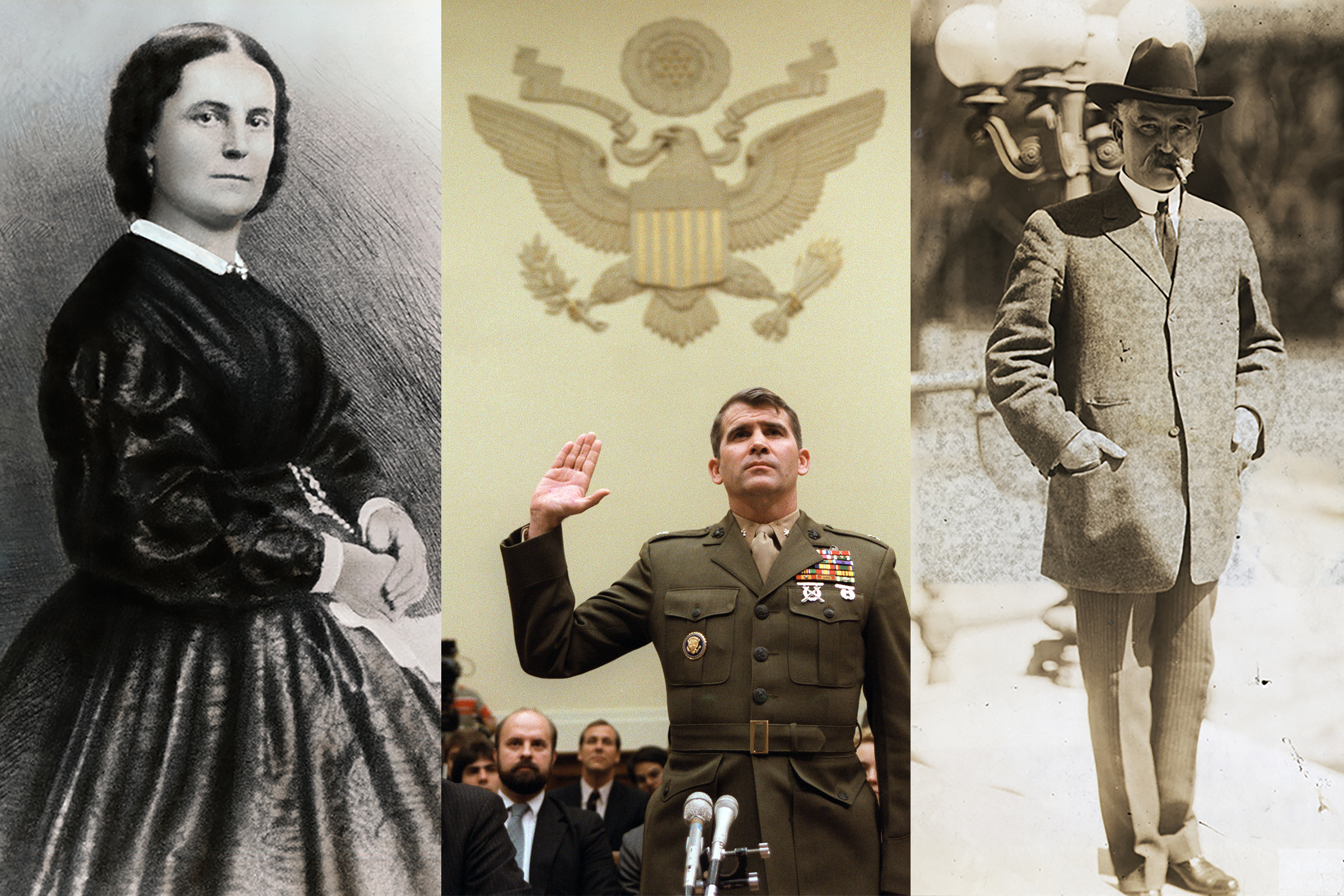

TIME asked seven historians to name the worst political scandal in American history. Here are their answers:

The XYZ Affair (1797-1800)

What happened: During the French Revolution, President John Adams sent a delegation to Paris to work out some issues after the French started searching U.S. ships that were en route to England. But the three French diplomats involved wouldn’t negotiate unless they were bribed. The U.S. officials refused and returned home. Amid questions over the perceived lack of progress, Adams made the meeting notes public, and the American people were outraged by the behavior of the French representatives — who showed up as X, Y and Z on redacted documents. This led to an undeclared, two-year naval war known as the Quasi War. A private citizen, Philadelphia doctor George Logan, took it upon himself to engage in private negotiations with French leaders, suggesting to them ways they could counter his government’s position.

Nominated by: Heather Cox Richardson, professor of History at Boston College and author of To Make Men Free: A History of the Republican Party

Why it was so scandalous: “In 1798, less than a decade after the adoption of the Constitution, Americans learned that French diplomats had refused to operate through official channels to keep the two nations from war. It threatened to replace the new country’s government of laws with a government of men whose private connections determined national policy,” Richardson tells TIME. “When they learned what Logan was up to, furious congressmen understood that the survival of the fledgling government itself was at stake. In 1799, Congress passed the Logan Act, designed to prevent foreign governments from working with private citizens to undermine American government policies ever again. ‘Any citizen of the United States, wherever he may be,’ the law reads, ‘who, without authority of the United States, directly or indirectly commences or carries on any correspondence or intercourse with any foreign government or any officer or agent thereof…to defeat the measures of the United States shall be fined… or imprisoned… or both.'”

The Eaton Affair (1829-1831)

What happened: In the first two years of Andrew Jackson’s term, his Secretary of War and good friend John Henry Eaton married Margaret “Peggy” O’Neale, the daughter of the owner of a boardinghouse that Eaton owned. But she became controversial because of her reputation for promiscuity, and the fallout led Jackson to dissolve his cabinet.

Nominated by: Joanne B. Freeman, Professor of History and American Studies at Yale University and author of Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic

Why it was so scandalous: “The scandal split the Jackson administration into two camps: Jackson and Secretary of State Martin Van Buren supported the Eatons, while much of Jackson’s cabinet decidedly didn’t — and their wives snubbed Margaret. Vice President John C. Calhoun joined the anti-Eaton forces, partly because he opposed Eaton’s support of protective tariffs,” Freeman explains. “Unable to resolve the problem through personal persuasion, Jackson ultimately forced pro-Calhoun, anti-Eaton cabinet members to resign in 1831. (Van Buren and Eaton also resigned to allow Jackson to appoint an entirely new cabinet.) In the end, the scandal caused a permanent rift between Jackson and Calhoun, and boosted Van Buren’s power and influence. Though very much of its time, the Eaton Affair shows how seemingly minor personal matters can have major political implications amidst the volatile blend of politics and society in the nation’s capital.”

The Crédit Mobilier Scandal (1872)

What happened: Crédit Mobilier, the company hired to build the Union Pacific Railroad, used its stock to bribe top officials in President Ulysses S. Grant’s administration — including the Vice President, the Speaker of the House and other members of Congress — to secure federal support to build a transcontinental railroad. The scandal came to light in 1872, but it took place in 1867 before Grant was President.

Nominated by: Manisha Sinha, professor of History at the University of Connecticut and author of The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition

Why it was so scandalous: “It was a prime example of corrupt crony capitalism that plagued the U.S. government,” says Sinha. “The tragedy of the Crédit Mobilier scandal was that it discredited the Grant Administration, even though the President was not involved in it personally, and [by extension the Administration’s] Reconstruction policy of protecting black rights against white terror in the post-Civil War South.”

Teapot Dome (1921-1923)

What happened: President Warren G. Harding’s Secretary of the Interior Albert Fall secretly accepted hundreds of thousands of dollars in Liberty Bonds in exchange for leasing former Navy oil reserves in Wyoming known as Teapot Dome to a private company. He became the first Cabinet secretary to go to prison because of his actions on the job.

Nominated by: Presidential historians Douglas Brinkley, author of American Moonshot: John F. Kennedy and the Great Space Race, and Robert Dallek, author of Nixon and Kissinger: Partners in Power, who both selected this moment, independent of one another

Why it was so scandalous: “The entire administration crumbled in his first term, right out of the gate,” says Brinkley. “It infected his entire close friend group and Harding became synonymous with cronyism and corruption. Scrutiny into Harding’s personal life led to the discovery that he had a mistress. [The scandal] puts so much pressure on President Harding that he died in office of a heart attack.”

“People in the government were selling the administration to the highest bidder, using their government power to exploit bad positions to make a lot of money,” says Dallek. “They weren’t interested in the national interest; they were interested in their self-interest.”

Watergate (1972-1974)

What happened: Tapes revealed that President Richard Nixon and his top advisors were involved in covering up a break-in at a Democratic National Committee office in the Watergate complex in Washington, D.C. Nixon resigned before he could be impeached, becoming the first President to step down. Several of his top advisors — including the White House lawyer, Chief of Staff and Attorney General — did prison time.

Nominated by: Barbara A. Perry, Director of Presidential Studies and Co-Chair of the Presidential Oral History Program at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center

Why it was so scandalous: The Committee to Re-elect the President was “using mechanisms of government to attack domestic opponents in the press and the political world, even breaking into the psychiatrist’s office of the Pentagon Papers leaker, Daniel Ellsberg, to see what kind of dirt they could use to smear him,” Perry explains. “That’s antithetical to what the country is supposed to stand for; we’re supposed to be a government of laws, not of men. Here is a president defying the law and breaking the law and the Constitution to secure a victory in 1972 — which they did, that part worked. It engaged all three branches of government, two of which countered the President and stood up to the scandal, and the fourth estate played a very large role.”

Perry says Watergate set a new bar for judging the seriousness of future political scandals: “Everything else is compared to that.”

Iran-Contra (1986-1989)

What happened: This Reagan administration scandal involved a secret arrangement to sell weapons to Iran, via Israel, to help fund the contras, who were the rebels fighting Nicaragua’s socialist Sandinista government. To do so was illegal for several reasons: It violated Congress’ limits on funding the group, the restrictions on selling arms to Iran and the federal government’s general strategy of not paying ransom for hostages, as the deal was set up in exchange for American hostages who’d been kidnapped by Hezbollah in Lebanon in the early 1980s. When the scandal came to light, Oliver North, a National Security Council staffer, was indicted for fraud and obstruction of justice and convicted of falsifying a timeline of events to Congress, shredding government documents when the news of the scheme came to light and illegally accepting a gift. (A judge dropped the charges in 1991.)

Nominated by: Julian E. Zelizer, Professor of History and Public Affairs, Princeton University and co-author of Fault Lines: A History of the United States Since 1974 with Kevin M. Kruse

Why it was so scandalous: “It involved high level administration officials really subverting the will of Congress and using secret deals/operations to get around what Congress said they couldn’t do,” Zelizer says. “Even worse, nobody was really held accountable for what happened. Many Republicans, like Richard Cheney [the future Vice President, then a Wyoming congressman, who was part of the joint congressional inquiry into the scandal], even doubled down and defended what the president’s men had done by saying it was their only option given the position of Democrats on the Hill. The failure to achieve accountability for executive action moved us back toward strong executive power after the post-Watergate reforms and gave rise to an entire generation of conservatives who defended extremely expansive views of the presidency.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com