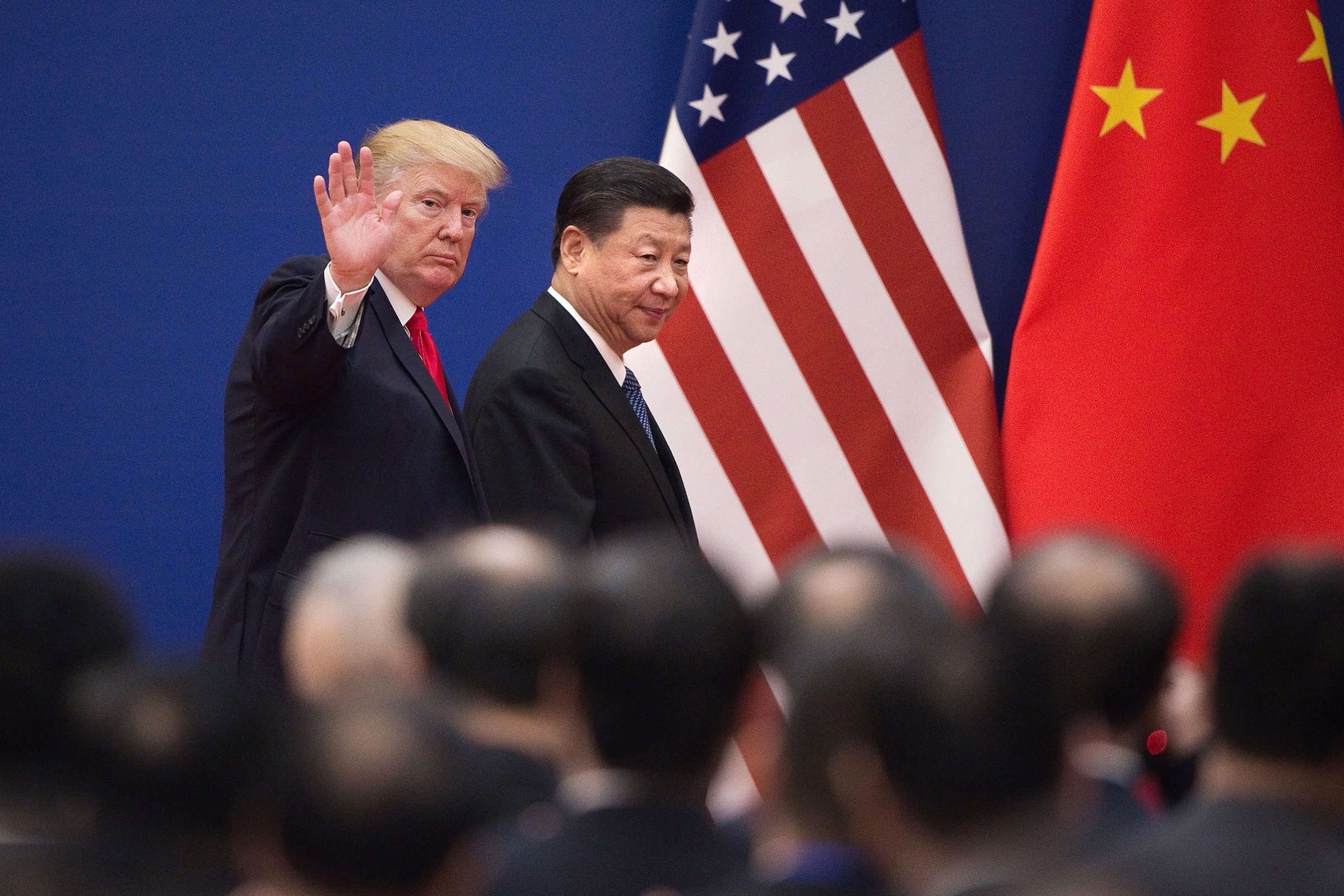

“We’re very well along,” says President Trump about U.S.-China trade talks. “Significant work remains,” caution his spokespeople. Negotiators representing the world’s two largest economies have worked hard for months to resolve long-standing conflicts over market access, protection of intellectual property, and other issues that led Trump last year to order billions of dollars in tariffs on Chinese goods. The two remaining outstanding goals appear to be U.S. willingness to quickly lift tariffs and Chinese willingness to allow the U.S. to verify that China is keeping its promises, but optimism is in the air that a deal will soon be done.

For good and for ill, there are significant similarities between this agreement and the 2015 nuclear deal the Obama Administration struck with Iran. Both involve lengthy, complex negotiations among teams of both technical experts and seasoned diplomats. As with the Iran deal, the U.S.-China agreement will be greeted with extraordinary fanfare. And, perhaps most important, these are both deals agreed to by the representatives of governments that deeply distrust each other.

That’s why a U.S.-China trade pact, like the Iran nuclear deal, is unlikely to last very long. One of Iran’s bitterest complaints is that the Obama Administration left many sanctions in place even after the nuclear deal was signed. Trump may well do the same with China, and the threat that Trump will abruptly tweet out new threats will hang over future relations. China, like Iran, will allow for some sort of verification process to prove it’s keeping its end of the deal, but the President may not always be satisfied with the result, particularly if U.S. and Chinese officials interpret the agreement differently, because of their economic interests and essential mistrust of each other.

A further similarity: other governments will be left with the mess when the deal breaks down. A series of reports issued earlier this month underscore just how many interested parties there are. The Asian Development Bank says trade disputes between Washington and Beijing create the most important current risk for Asia’s regional economy. The International Monetary Fund notes that today’s global supply chains leave South Korea and Japan, as well as Germany, Italy, the U.K. and France, especially vulnerable to an economic slowdown triggered by tariffs. The World Trade Organization warns that tit-for-tat tariffs, like those at play in the U.S.-China trade war, threaten global jobs, growth and economic stability.

Donald Trump wants a deal. He needs a major political win to open his campaign for re-election, and there are few other foreign policy achievements he can credibly claim. Chinese President Xi Jinping wants a deal too. He’s managing a long-term slowdown of China’s economy and needs to avoid criticism at home that the “new era” of Chinese power he has proclaimed has forced his country and its economy into an unwelcome international spotlight. The negotiators representing the two governments want an agreement that will satisfy the political needs of their Presidents while resolving enough problems in U.S.-China trade relations to give the deal a chance to stand the test of time.

But mistrust extends well beyond the men at the top. China and the U.S. will compete for domination in coming years across the political, economic, security and technology arenas. A signed agreement can make an important difference to limit this competition. It can also be destroyed more quickly than it was constructed. Just ask Iran.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com