The loss of a parent challenges most children, no matter their age. But when the parent is both beloved and deeply flawed, as Katharine Smyth’s father was, that grief can be difficult to parse.

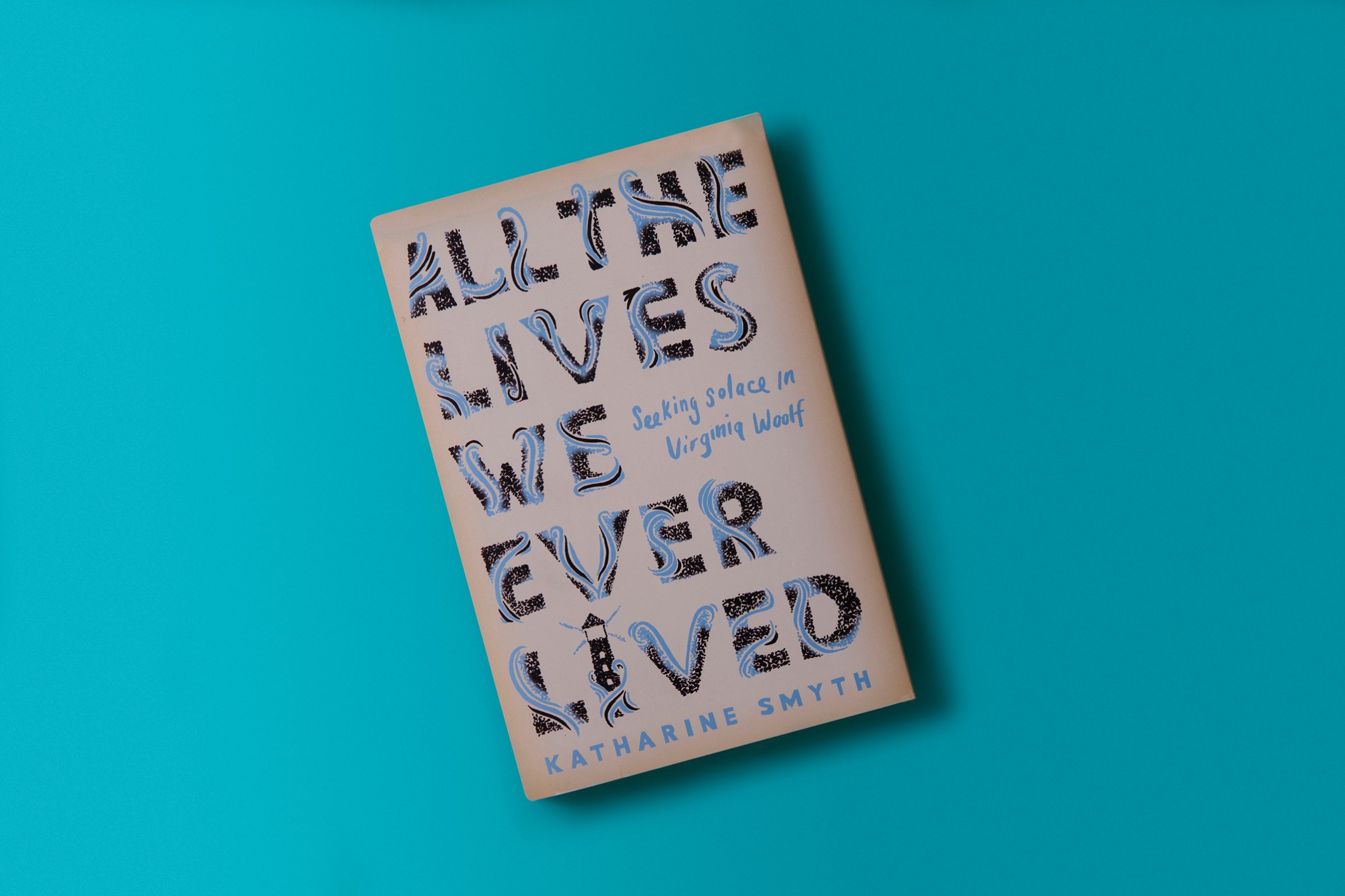

In All the Lives We Ever Lived: Seeking Solace in Virginia Woolf, Smyth turns to an unlikely source of solace after her father’s death: her favorite book, Woolf’s 1927 masterpiece To the Lighthouse. Blending analysis of a deeply literary novel with a personal story is a high-wire act for many reasons, not least being how few readers will have read Woolf themselves. But Smyth, who earned an M.F.A. in nonfiction from Columbia, is up to the challenge, gently entwining observations from Woolf’s classic with her own layered experience.

Smyth tells us of her love for her father, his profound alcoholism and the unpredictable course of the cancer that ultimately claimed his life. She admits that she doesn’t understand him. As she navigates her sense of loss, she discovers that the structure of To the Lighthouse–in which a family’s seemingly perfect past and unsure future are bridged by a stormy present–is more than a literary device. It’s a statement that speaks directly to her needs, “an endeavor to speak to and rectify grief’s essential formlessness.”

Smyth finds a way to translate how fiction helps us understand that formlessness, and the way in which even the death of a close relative, especially in a sanitized hospital setting, can feel remote and inaccessible. As she searches for truths about her father, Smyth accepts that nothing–not his corporeal self, not his character, not his history–can be fully known. In To the Lighthouse, Mr. Ramsay quotes a poem: “And all the lives we ever lived and all the lives to be/ Are full of trees and changing leaves.” In writing her own book, Smyth has discovered a way to appreciate the changing leaves, one that works both as memoir and as an aid to those who mourn.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com