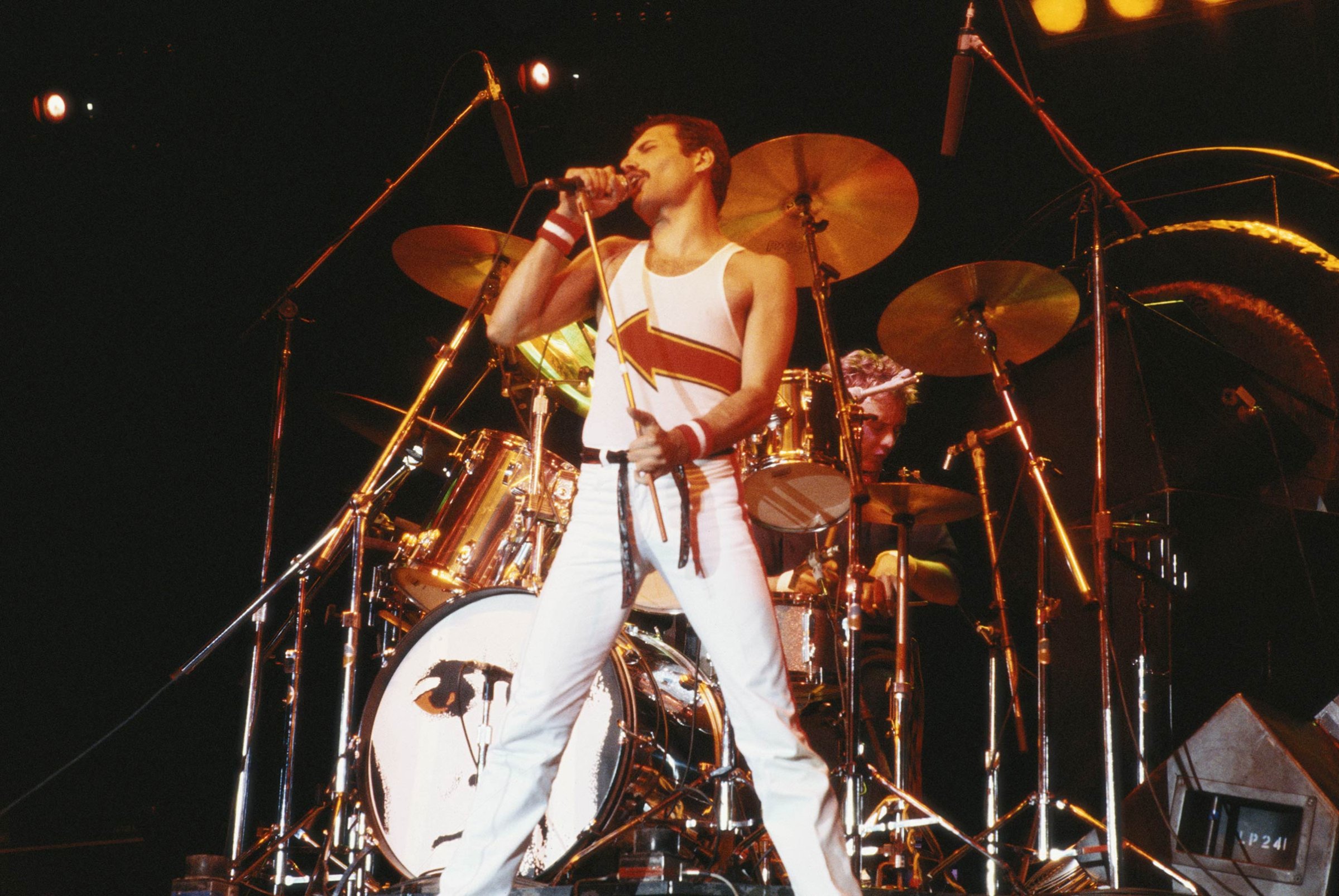

In the new biopic about Freddie Mercury — Bohemian Rhapsody, in theaters Friday — the Queen lead singer (played by Rami Malek) has one request when he tells his bandmates about his HIV diagnosis: that they keep the news private, because he doesn’t want to be a “poster boy” for AIDS or a “cautionary tale.”

While Mercury is remembered more for his music than for anything, his health status did in fact become public just days before he died of complications of AIDS-related pneumonia on Nov. 24, 1991, at the age of 45. And in fact, even if the timeline of his diagnosis in real life doesn’t quite match up with its film version, that real-life announcement was one of several that raised awareness of the epidemic.

About 72,000 attended a benefit tribute concert held at London’s Wembley Stadium, almost five months after his death, raising millions for AIDS research. And since those who worked with Mercury established The Mercury Phoenix Trust 21 years ago, the organization says it has donated over $15 million to the cause.

Mercury’s reticence was understandable. He was reportedly diagnosed in 1987, a time when some countries, like the U.S., wouldn’t let HIV-positive people immigrate. Nevertheless, he became just one of several high-profile figures who, in life and death, raised awareness about the disease — though experts are careful to point out that the celebrities were generally following in the footsteps of a movement that already existed.

“Stars would have done nothing if the public was silent, if not for the extraordinary grassroots activism,” says Ronald Bayer, an expert on the history of AIDS and Co-Director of the Center for the History and Ethics of Public Health at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health.

But getting stars to speak up was vital at a time when President Reagan’s administration “was in total denial,” as Bayer puts it, and more treatment options were desperately needed. And by the time Mercury died, it was already clear that celebrities could make a major difference. Case in point: Rock Hudson.

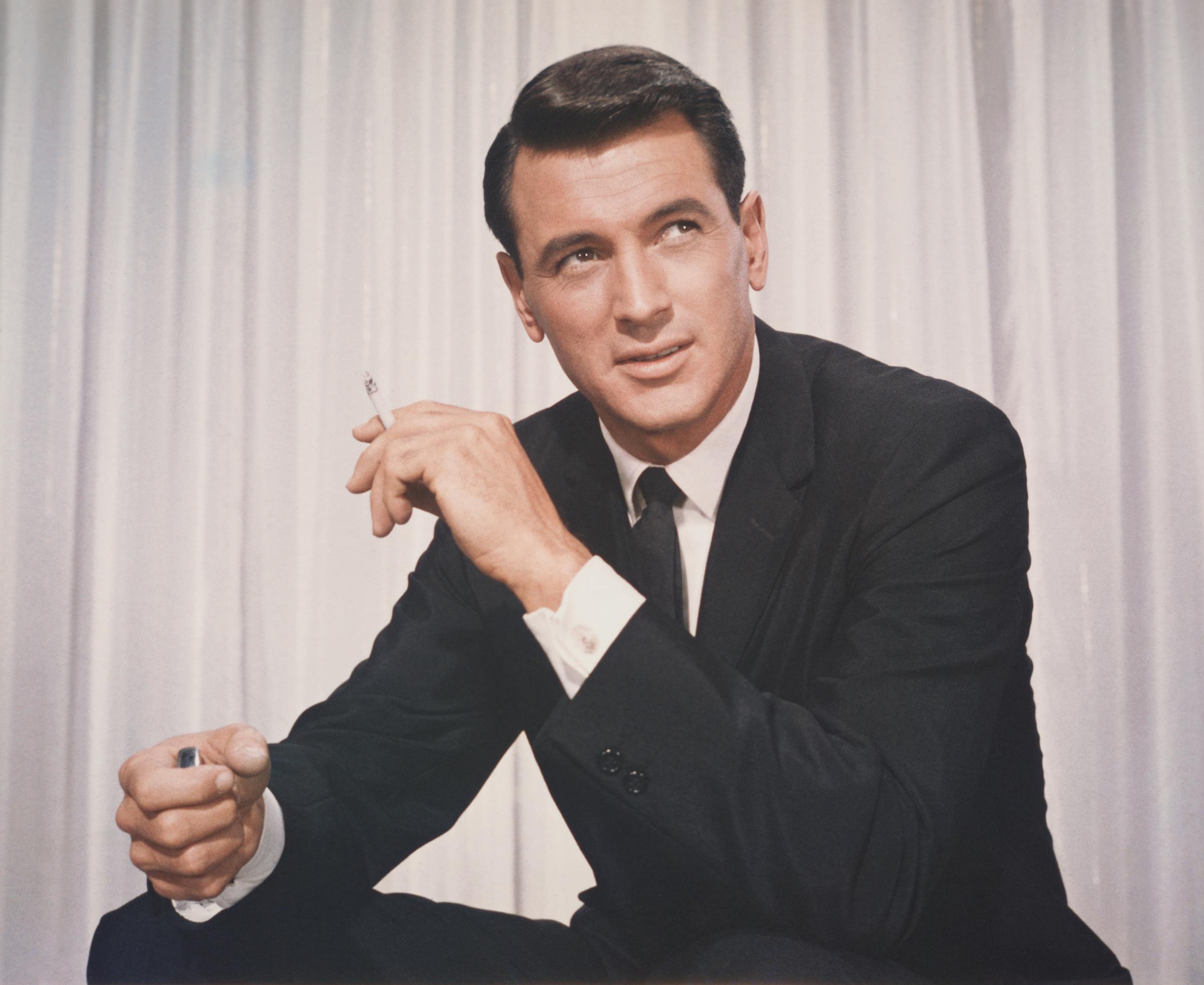

When the Oscar-nominated star announced that he had AIDS in July 1985, it was enormous news for two reasons. Not only was the disease poorly understood, but Hudson’s diagnosis was also symbolic. As TIME pointed out when the news broke, he had “represented the old-fashioned American virtues” of the 1950s, so some were shocked by a diagnosis that was seen to function as a simultaneous announcement that he was gay; at the time, though many insiders were said to know about Hudson’s sexuality, the magazine was able to declare that no major movie star had ever come out.

The shock precipitated a TIME cover story on AIDS later that summer, in which the magazine described the impact of Hudson’s announcement:

By early this year, most Americans had become aware of AIDS, conscious of a trickle of news about a disease that was threatening homosexuals and drug addicts. AIDS, the experts said, was spreading rapidly. The number of cases was increasing geometrically, doubling every ten months, and the threat to heterosexuals appeared to be growing. But it was the shocking news two weeks ago of Actor Rock Hudson’s illness that finally catapulted AIDS out of the closet, transforming it overnight from someone else’s problem, a “gay plague,” to a cause of international alarm. AIDS was suddenly a front-page disease, the lead item on the evening news and a frequent topic on TV talk shows. There seemed no end to the reports.

Hudson died less than three months later, at the age of 59. The TIME obituary described him as “the most celebrated known victim of AIDS” who “[i]n the last weeks of his life…became perhaps the most famous homosexual in the world.”

And, within two months of his announcement, Congress had approved a vast increase in funding for AIDS research.

“From his misfortune good fortune may have sprung,” that obituary concluded. “His friend and Giant co-star Elizabeth Taylor wrote perhaps the most eloquent epitaph: ‘Please God, he has not died in vain.'”

Taylor would become a key fundraiser for the cause at the height of the epidemic. The month before Hudson died, she had been a hostess and co-chairperson of what’s been called the first major Hollywood benefit gala for the cause, which raised about $1.2 million for AIDS research amid what TIME called “a growing panic” in Hollywood about contracting the disease. She was also a co-founder of the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR); appeared before the Labor, Health and Human services Senate Subcommittee to urge the passage of $80 million in funding for AIDS research; and in 1991 established The Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation. When she died about 20 years later, her obits credited her with raising about $100 million for AIDS research.

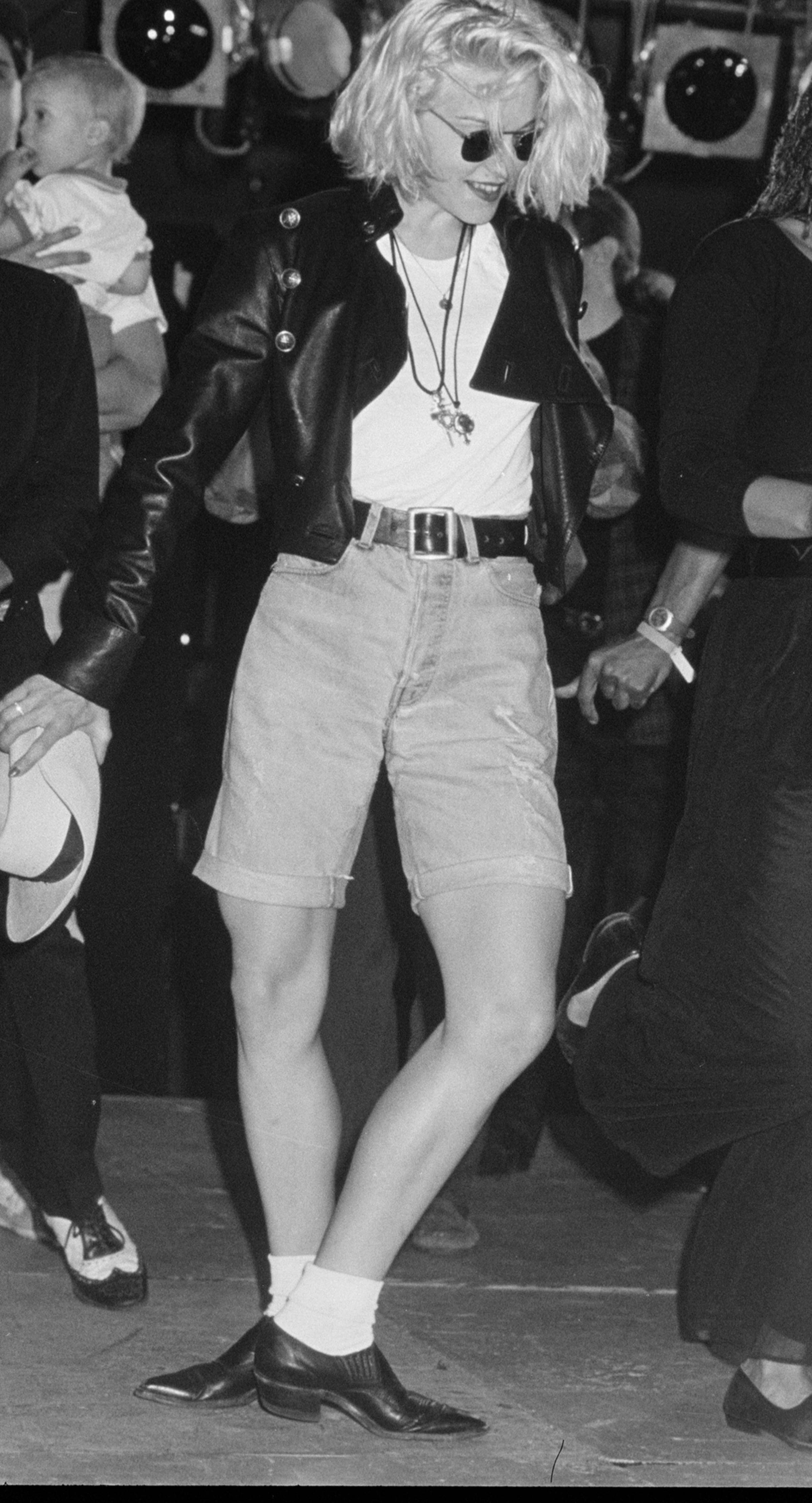

And Taylor wasn’t the only non-HIV-positive celebrity who was inspired to get involved. Celebrity diagnoses caused an awareness chain reaction: when someone whose friends were famous was HIV-positive, those celebrities were often moved to speak up. For example, Madonna performed for 15,000 at a benefit concert at Madison Square Garden in July 1987, shortly after the death of her close friend, the painter Martin Burgoyne, from the disease.

Such occasions had become “depressingly frequent occasions for New York’s beau monde,” as TIME’s Richard Corliss put it back then.

The concert raised $400,000 for amfAR. Madonna’s album 1989 Like a Prayer also included an insert, “Facts About AIDS,” to encourage safe sex. During her Blond Ambition tour, she paid tribute to another artist friend who died due to AIDS, Keith Haring. (Some of her dancers who performed with her had been diagnosed but weren’t talking about it.)

In fact, she had been so outspoken that in 1991 there were false rumors that she was planning a press conference to tell the world that she had been diagnosed as HIV positive. AIDS activists slammed the rumors as homophobic and worried that the hype would discourage HIV-positive patients from disclosing their status.

That year, however, did see one of the most important real disclosures by a celebrity.

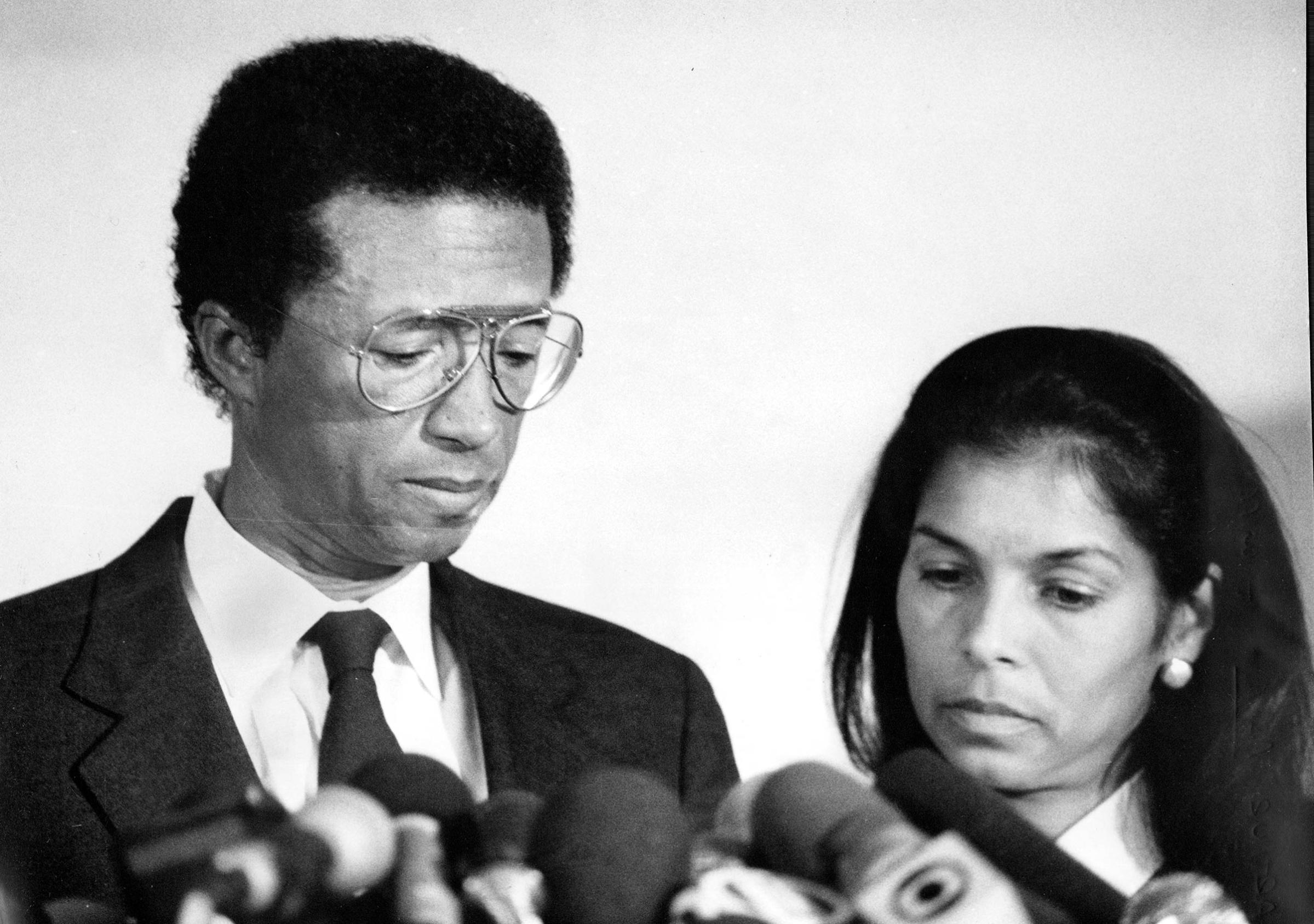

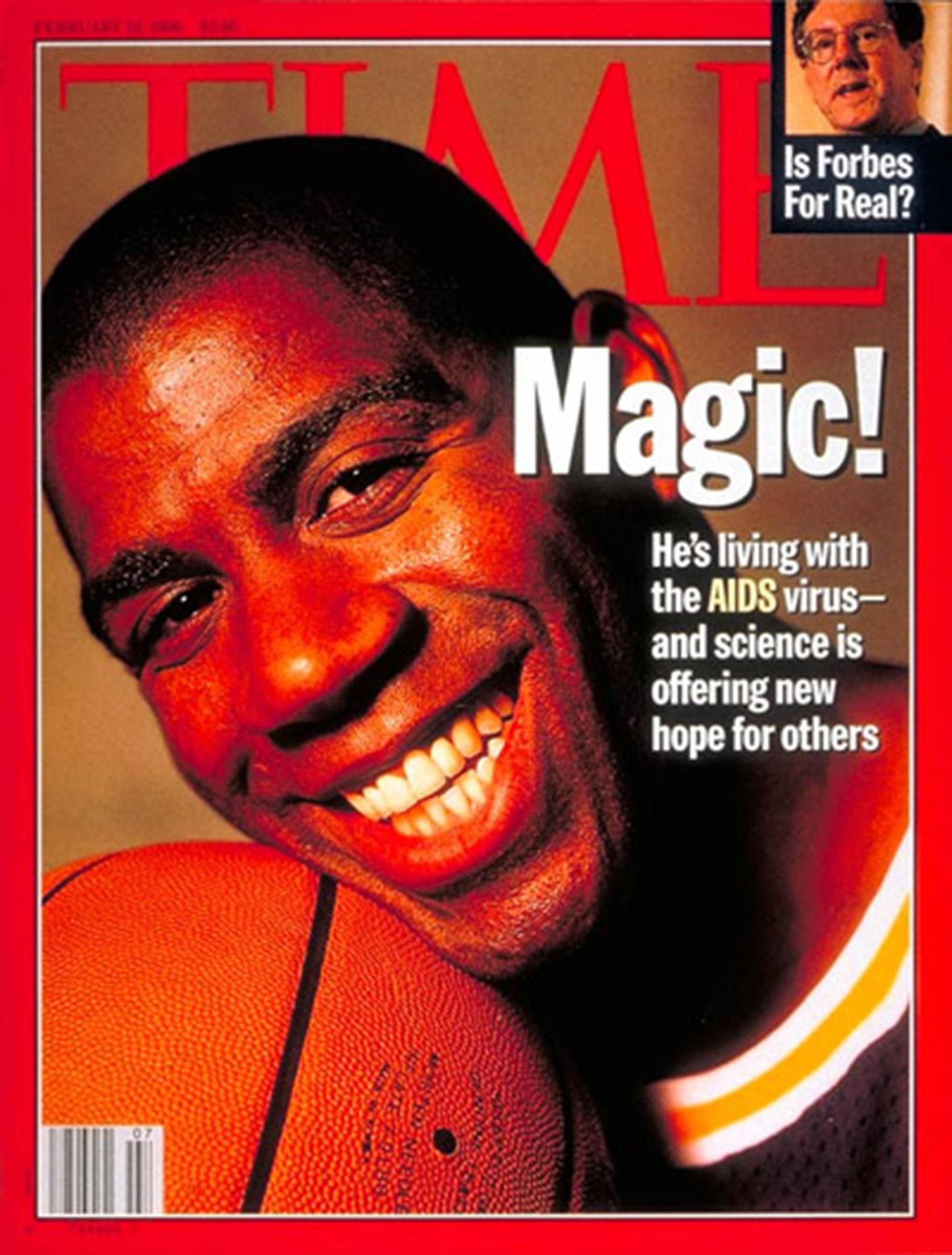

On Nov. 7, 1991, 32-year-old L.A. Lakers point guard Magic Johnson revealed in a press conference that he was HIV-positive and would be retiring from basketball. “I will now become a spokesman for the HIV virus” and safe sex, he said.

The fact that he was a heterosexual African American athlete further underscored the fact that AIDS could affect anyone. And lots of misconceptions needed to be debunked; some basketball players, for example, refused to play with Johnson because they thought they might get infected that way.

The impact of his announcement started to be seen right away. “Calls to AIDS hot lines and testing centers more than doubled in most places the next day,” TIME reported after the news broke. High schools doubled down on condom distribution. “[Because] he would not discuss how he might have contracted the disease but only implied it was from heterosexual contact, he drove home the fact that anyone is vulnerable. Johnson is also ideally placed to speak on AIDS to the two groups that are most in need of counsel: impoverished minority communities and the young.”

“Clearly this is tragic,” said Norm Nickens, chairman of the National Minority AIDS Council, at the time. “But we couldn’t ask for a better spokesman.”

Five months after Johnson’s announcement, Arthur Ashe — the first African-American man to win a Grand Slam title — became the second major sports figure to reveal that he too had been diagnosed with HIV. He had likely contracted it after receiving a blood transfusion while undergoing surgery, but had kept the diagnosis private until USA Today asked him to respond to rumors that he had the disease.

“It was just bad luck that Ashe underwent major surgery after the AIDS epidemic began but before tests to detect the virus in the blood supply became available in 1985,” TIME reported. “Since then, only 20 of the nation’s more than 200,000 AIDS cases have come from transfusions of tested blood, while nearly 4,500 have been attributed to untested blood. Nowadays, according to the Centers for Disease Control, the chances of contracting the disease from a transfusion are 1 in 61,000. More people are killed by lightning.”

By the time Ashe died on Feb. 6, 1993, he had established the Arthur Ashe Institute for Urban Health, was active in AIDS research efforts at Harvard and UCLA, and gave speeches to raise awareness. Shortly after his death, his wife, photographer Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, wrote a children’s book about Ashe and his young daughter to raise awareness about how a parent with the disease can still raise a child and live a fulfilling life.

As the 1990s continued and AIDS research made serious progress, celebrities were an important factor in keeping that ball rolling.

For example, actor Jeremy Irons is credited with popularizing the wearing of a red ribbon to raise awareness about HIV/AIDS research, having worn one while hosting the Tony Awards on Jun. 2, 1991. The brainchild of activist group Visual AIDS, the organization once said the color red was chosen “because of its connection to blood and the idea of passion — not only anger but love.” That awards ceremony was targeted because the epidemic had hit the theater community particularly hard.

And it was during the same period that Elton John established the Elton John AIDS Foundation, partly inspired by the friendship he had formed with Ryan White, an American teenager whose treatment after an AIDS diagnosis made headlines in the late 1980s. John has also said that he took up the cause of AIDS awareness because he felt he had dodged a bullet by managing not to get infected. As he said in 2012, “By all rights I shouldn’t be here today. I should be dead – six foot under in a wooden box. I should have contracted HIV in the 1980s and died in the 1990s, just like Freddie Mercury, just like Rock Hudson. Every day I wonder, how did I survive?”

In the summer of 2018, his foundation launched a $1.2 billion partnership with Duke of Sussex Prince Harry, focused on boosting diagnosis and testing of young men ages 24 to 35. Harry’s mother Princess Diana had also championed the cause, shocking the world in 1987 when she shook a patient’s hand without wearing a glove during the opening of the first ward for HIV/AIDS patients at Middlesex Hospital in London. At the time, many people erroneously thought they could get the virus from that kind of casual contact. The stigma was so pervasive, however, that the patient in the photo was reportedly the only one in the ward who agreed to be photographed, and only on the condition that his back would be facing the camera.

The work celebrities did at the outset of the AIDS epidemic paid off in ways that go beyond the important work of destigmatization. Thanks in part to the money and awareness they helped raise, great progress has been made in the years since Freddie Mercury died.

Just a few years after Magic Johnson left the NBA, treatments had advanced enough that he felt well enough to return to basketball in January of 1996, signing a $2.5 million contract for the second half of the season. “Enjoy life,” he was quoted saying at the time. “Live. I’m not just talking about people with HIV or AIDS, but about people with problems or handicaps or whatever. For people who have HIV, come out and share your life with somebody and make them feel better.”

His NBA career ended that spring, though internal disagreements with coaches and teammates — not his health — were cited as the reason. But his career as a HIV/AIDS awareness spokesperson is still going strong.

After all, because there’s still no cure for HIV or AIDS, the role stars play in amplifying grassroots activism is no less important today than it was when Freddie Mercury first made news.

Correction: Nov. 5

The original version of this story misstated the name of a Columbia University expert. He is Ronald Bayer, not Robert Bayer.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com