Season 3 of the true-crime podcast Serial doesn’t explore any brutal murders where the facts don’t add up. Its subjects aren’t famous. They can’t afford expensive defense attorneys who dramatically unearth DNA evidence. Instead, they’re bar brawlers, parole violators and people caught carrying a joint. These cases rarely make the news, though some should, like the story of an innocent man who was pulled over and beaten by a cop for — by the police officer’s own admission — no reason. They are simply the tales of ordinary people who pass through Cleveland’s courthouse.

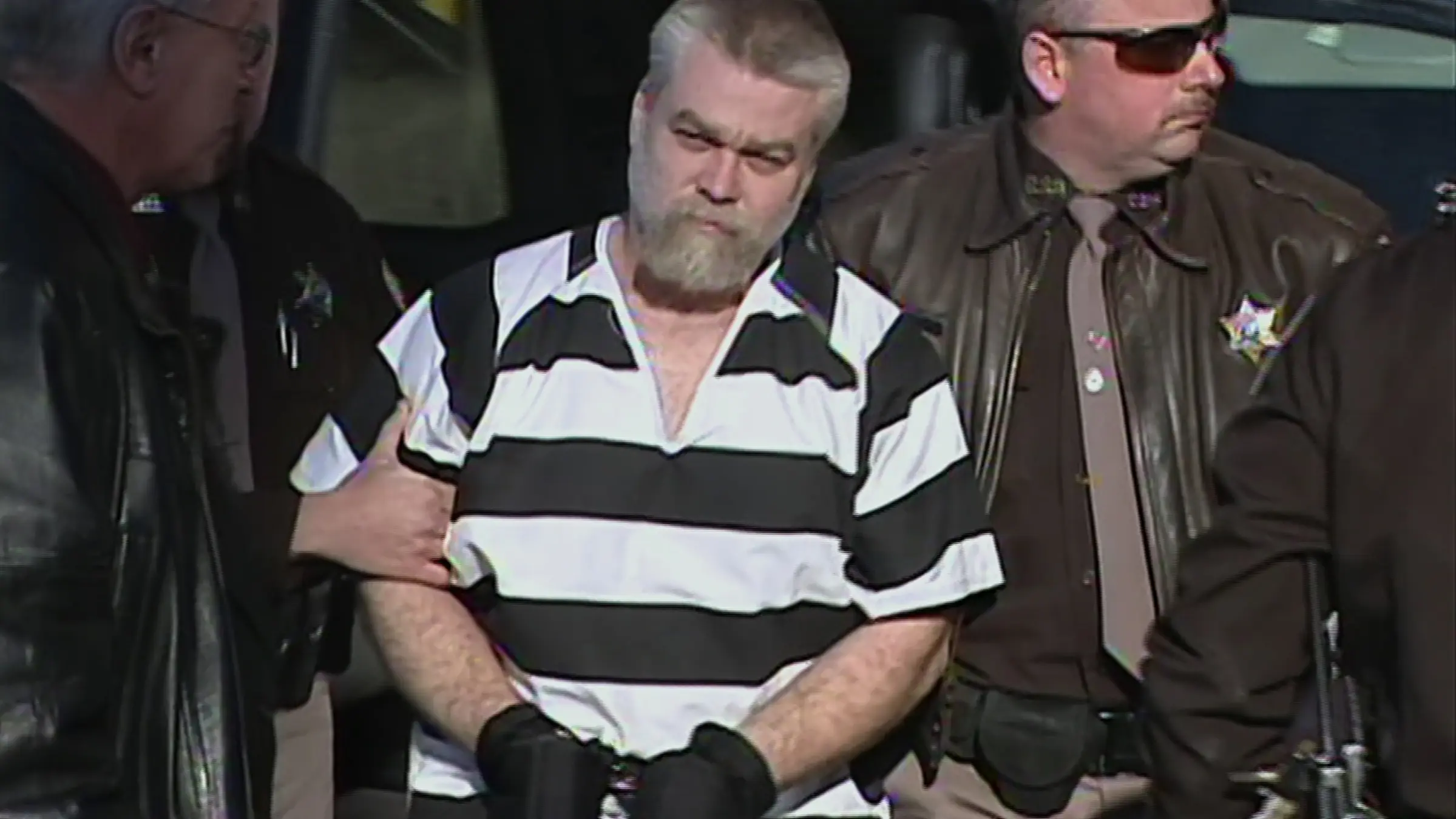

It’s a conscious change for a podcast that became a pop-culture phenomenon in 2014 by examining the murder of Baltimore teen Hae Min Lee, allegedly at the hands of her classmate Adnan Syed. The podcast’s new direction also diverges from most shows in true-crime drama, which can tend toward the salacious even when trying to educate or effect change. Making a Murderer, for instance, earned a rabid fan base in 2015 when it took on the story of Steven Avery, a man who has been convicted twice and exonerated once.

Both Serial and Making a Murderer faced backlash for lending a too-sympathetic ear to potential perpetrators. The two shows have since taken different paths: Making a Murderer returned to Netflix in October to follow Avery’s appeals process in new episodes, while Serial has wisely ventured into new territory.

Serial host Sarah Koenig addresses the pivot in the first episode of the new season, which premiered in September. “People have asked me, ‘What does [Syed’s] case tell us about the criminal-justice system?'” she says. “Fair question. The answer is that cases like that one, they are not what fills America’s courtrooms every day.”

As local news organizations fold under financial burdens, courthouse beat reporters have become increasingly rare. True-crime storytellers now have the opportunity to step in and report on the daily miscarriages of justice in order to examine the systemic problems in our legal system. Serial landed in Cleveland by happenstance: the city, unlike others, allows microphones in its courtrooms. But the Ohio metropolis represents every town. “We tried to look for a place that wasn’t extraordinary in any way,” producer Julie Snyder tells TIME.

Compared with the first season of Serial — which broke streaming records, spawned Reddit conspiracy theories and earned a Saturday Night Live parody — the show’s third season sounds like homework. But the banality with which judges and lawyers change the course of people’s lives proves fascinating — and disturbing. In one episode, Koenig interviews a judge who regularly says he will put parolees in jail if they have a child out of wedlock. It’s a jaw-dropping, unconstitutional condition. But judges and lawyers in Cleveland respond with a shrug: declarations like this are unfortunate but inevitable.

Filmmakers have long raced to document sensational crimes. But in recent years, some journalists have begun to rigorously examine the more quotidian injustices that often go ignored by the media. Tales of serial killers feel less pressing than the larger narrative of racist and classist biases that pervade the justice system. Serial‘s third season suggests that storytellers might be better served examining ordinary cases, not extraordinary ones. “We’re talking about a criminal-justice system in crisis,” says Snyder. “We feel a duty to explore how that system actually works.”

All true-crime entertainment exists on a sliding scale. Some shows, like the popular podcast My Favorite Murder, shamelessly mine tragic tales to fulfill our most voyeuristic desires; others have loftier goals. The second season of Making a Murderer struggles to find the right balance. Avery’s post-conviction lawyer Kathleen Zellner combs through every potential lead — including the personal life of victim Teresa Halbach — to find other possible perpetrators. She’s doing her job. But in front of the cameras, her work can feel tasteless, even reckless.

Making a Murderer is also muddied by the media frenzy it created. The filmmakers often interrupt Avery’s appeals process to show his onetime fiancée soliciting relationship advice on Dr. Phil, or the man who prosecuted Avery promoting his book on Dateline. “It all became a part of the story,” says Moira Demos, who co-created the documentary with Laura Ricciardi. “How do headlines compare to what’s really happening on the ground?” But these side plots distract from the very real obstacles Avery faces.

The visual nature of the medium doesn’t help. Cameras tend to linger on bloodstains. Though some podcasts indulge in lengthy descriptions of corpses, the audio format feels less prurient. And podcast hosts can establish an intimacy with the listener that filmmakers cannot: they can express skepticism or empathy during interviews. Some documentarians, in their determination to remain objective, run the risk of removing themselves from the narrative to their own detriment. Making a Murderer‘s creators use a montage of newscasters debating the ethics of their show, but they stop short of responding to that criticism themselves.

By contrast, the Peabody-winning podcast In the Dark feels allergic to sensationalism. For the second season, released this summer, the creators moved to Winona, Miss., to investigate the case of Curtis Flowers. A white prosecutor convicted Flowers, a black man, of the same murder six times — with the first five trials ending in either overturned convictions or mistrial. Over 11 episodes, host Madeleine Baran thoroughly dismantles the case. But the off-the-cuff attitude of some of her interviewees speaks volumes.

In one episode, a former Mississippi supreme-court justice argues that Flowers’ case proves the system works: every time he was convicted, the ruling was overturned. When Baran points out that Flowers has been in prison for years as the prosecutor pursued the case again and again, the former judge replies, “While his specific physical situation might not change much, his status as a convicted felon vs. his status as an incarcerated person awaiting trial has … There is a big distinction.” He may be technically correct, but the reality for Flowers is devastating.

Systemic racism haunts In the Dark and Serial. Judges and lawyers speak in dog whistles. African Americans hesitate to call the police because of a lack of trust.

The true-crime podcasts that came after Serial‘s first season rarely addressed topics like this. But in an era when so many Americans feel that injustice is the norm and truth is subjective, these stories have a greater responsibility not only to report on the craziest cases but also to say something meaningful about how daily instances of discrimination and corruption poison society. In their new installments, Serial and In the Dark demonstrate that true crime can be more than just a guilty pleasure.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Eliana Dockterman at eliana.dockterman@time.com