“Put my dad on the breathing machine,” Ms. D. told me earlier this year, as tears ran down her cheeks in the emergency department at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Ms. D. had brought her father here when she found him less alert and gasping for air. He was a man in his 80s, suffering from advanced lung cancer. Doctors had told him that he was dying, and he was receiving hospice care at home. At this moment, while my clinical team was stabilizing the patient, still gasping for air, I thought to myself, What is the chance that this patient will die regardless of what I do? And how can I deliver the care that is best for him?

If placed on the breathing machine, a plastic tube is inserted through the mouth down to the lungs, and you are unconscious — uncomfortable and unable to communicate with others. This arrangement will likely require other invasive measures, like inserting catheters into deep veins and the bladder, to maintain human physiology. Unless there is a clear path to come off the machine, I don’t believe most patients would consider this arrangement an acceptable way of “living,” and yet so many of them experience it as their final form of life.

Breathing machines were originally designed to reduce the work of breathing until surgery, an infection or some other acute critical condition was resolved. But they are now commonly used for seriously ill older adults. If they are lucky enough to survive, they often require prolonged time in hospitals and then, for days to weeks if not months, a rehabilitation facility.

In 2011, 497,496 older adults received this care in the U.S. — an amount projected to double by 2020. The rate of increase is four-fold higher in patients with dementia whose conditions may never end.

Part of the reason for the popularity of this undesirable process is that, when faced with a life-or-death decision, selecting the appropriate seriously ill patients who recover from the breathing machine is not straightforward. Predicting how much longer the patient will live, managing the acute illness, exploring the values and preferences of the patient and making a recommendation on how to proceed — these actions are complex, especially during a life-or-death situation. It is in these moments that doctors must choose when intervention itself is the best approach to help the patient, particularly if they are unlikely to recover.

Regarding predicting how much longer patients will live, I recently published a study about what would happen to older adults if they were placed on a breathing machine. I analyzed 35,000 patients who were older than 65 years and placed on breathing machines, across 262 hospitals between 2008 and 2015. I found that a third of those patients died in the hospital. Most survivors (63%) were discharged to locations other than their home, presumably to nursing facilities (We do not know if these were short rehab stays or permanent placements.).

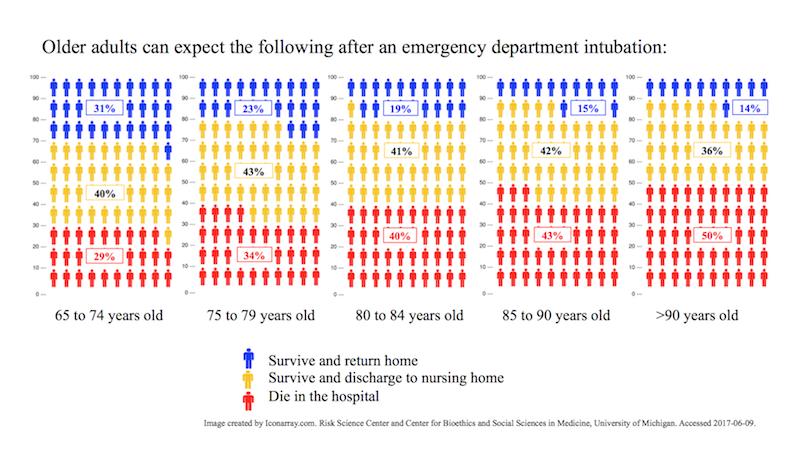

Among other things, age is still an important factor here: 31% of patients ages 65 to 74 survive the hospitalization and directly return home. But for 80- to 84-year-olds, that figure drops to 19%; for those over age 90, it slides to 14%. One of the important conditions that worsens one’s chance of survival is metastatic cancer. With this information, clinicians must communicate with the patient or their surrogate about how much the patient would be willing to go through.

To help with this decision-making, I created the following illustration to help clinicians and patients think together:

I designed this illustration, enabling clinicians and patients to visualize the chances of survival. A clinician may use the illustration to follow along while explaining to a 70-year-old patient that, if ever placed on a breathing machine, she has a one-in-three chance of dying in the hospital, and about equal chance of returning home. This illustration is based on an average of many patients, and the numbers are worse if patients are older or have other serious illnesses like cancer. A variety of shared decision-making aids for patients with serious illness are available, yet their use is not widespread in clinical practice to date.

There is a caveat to using this tool or any shared decision-making aids, though: this must be presented and discussed when patients and surrogates have the cognitive ability to understand this information. This cannot happen during a moment of emotional crisis, during which, regardless of decision maker’s education or intelligence, humans cannot understand cognitive information like one’s chance of survival. It’s these types of moments when we must talk with the patient or their surrogate about what is in their best interest.

In the heat of the moment in crisis, it is easier for clinicians to just place a patient on a breathing machine. It can feel like an answer. But it is not always. Instead, it can be means of avoiding a tough, emotional conversation to decipher what the patient or surrogate really want in this situation. However, this is precisely the moment when carefully tailored decisions to meet the patient’s goals are essential.

Ms. D. was simply asking to help her dad. Knowing that the patient would likely die no matter what we do, I tried to find out what is most important to the patient.

I told her that I was worried that no matter what we do, her father may die. I acknowledged that she knew her dad the best, and that I knew the medicine best, and asked if we could decide together what would be best for her dad on that day.

When she said that was okay, I asked and learned about how her father had been doing at home. I said to her, “It must be very difficult to watch him suffer. I assure you that we will do our best to help him get the care he needs. What did your dad tell you about what’s important to him he if got sicker?”

She replied, “He told us that he needs to be able to talk and be around his family as long as possible, even though he is dying.” To me, this showed that Ms. D. seemed to be most worried about watching him suffer and unable to grant the patient what he said was important to him. I told her that was my assessment, which she confirmed. And it was only then that I made my recommendation.

I decided against the breathing machine. Instead, I counseled an intensive breathing therapy to help him breathe while allowing him to be as conscious as possible. I told Ms. D., “I would not place him on breathing machine because that will not allow him to have a chance to interact with you again. If we are lucky, he may be able to respond to you in his own ways. Would that be okay?”

“Yes, thank you,” she replied. “Please help him….”

Her father died three days later in the hospital. It is unclear if he spoke back clearly; yet they spent hours connecting to each other along with their family, breathing as comfortable as humanly possible before he stopped.

Clinicians may not be able to cure cancer, defeat death or bring back the much-needed time between the patient and the loved ones. But we can reduce a patient’s suffering as much as possible by aligning patient’s goals to the care that they receive. Our reflex to use a breathing machine, even when doing so would mean defying the odds and going against the patient’s wishes for the rest of their life, shows how much we can still improve.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com