As the 90s dawned things were looking up for women. Daughters of second-wave feminism came of age and chose new paths unavailable to their mothers: delaying marriage and children, pursuing higher education, joining the workforce, and assuming independence and identities outside of the home. The gaps between men and women in education “have essentially disappeared for the younger generation,” declared a 1995 report by the National Center for Education Statistics. The equal education promise of Title IX was coming to fruition.

For more than a century, the median marriage age for women swung between 20 and 22, but in 1990, it nearly jumped to 24. By 1997 it reached 25. Postponing marriage and kids liberated women sexually; it also gave them increased economic power and paved their entry into male-dominated careers. Almost half of married women surveyed in 1995 reported earning half or more of their total family income, leading the study’s sponsor to declare, “Women are the new providers.”

The forward motion of the 90s seemed to build on the 80s, a decade of hallowed female pioneers in diverse fields. Sally Ride traveled to space. Geraldine Ferraro secured the vice presidential nomination of a major political party. Alice Walker and Toni Morrison won Pulitzer Prizes for their epic, women-centered fiction. Madonna smashed barriers in music, entertainment and popular culture. Because these firsts and many others were so widely celebrated, society assumed these trailblazing women would also cut a path for all women to advance in work, entertainment, politics and culture in the years to come. At last, the dream of gender equality would be realized.

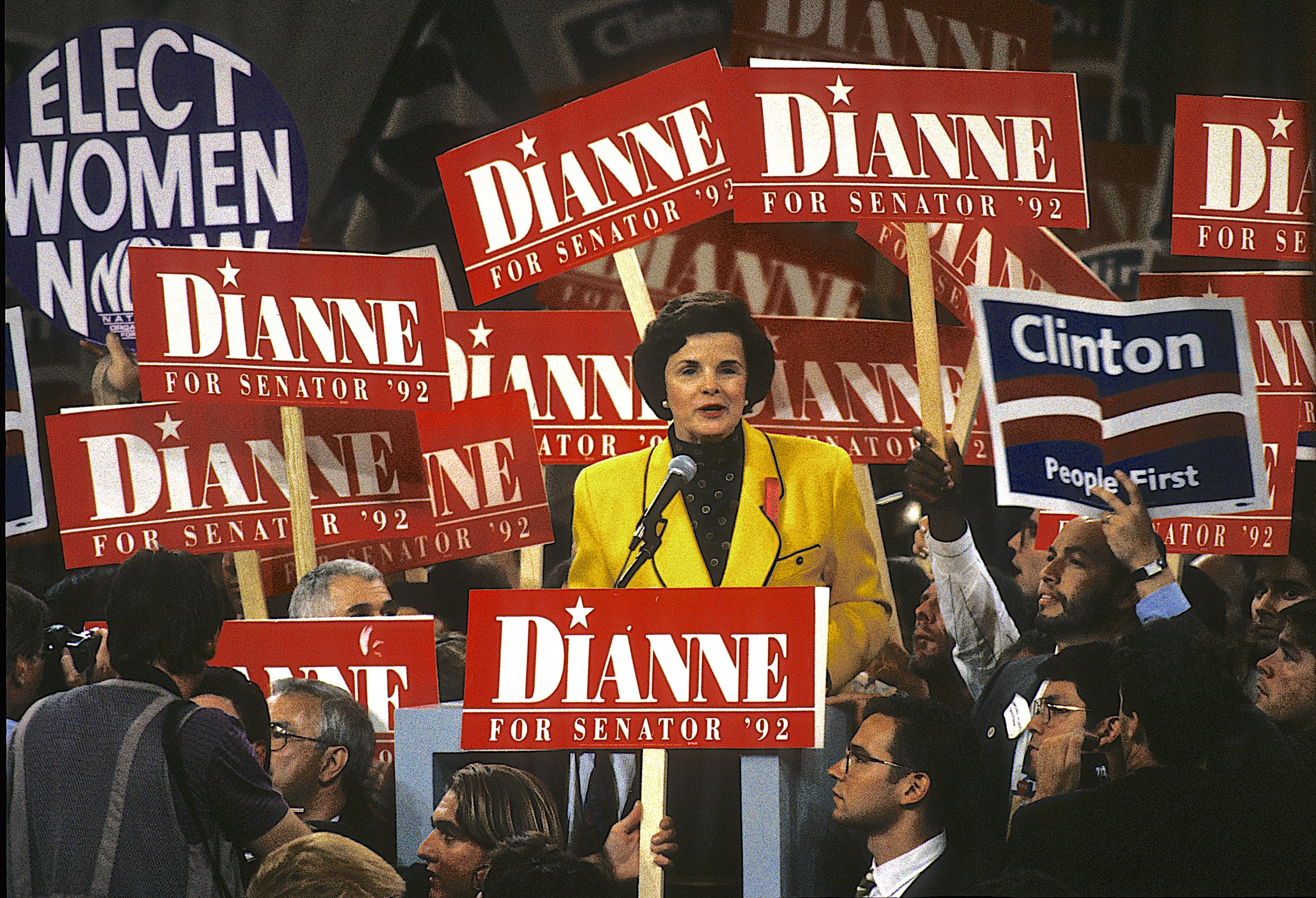

The dream, as we know, was not realized. But a quick glance back at the 90s would suggest that American women indeed made significant progress during the decade. In Janet Reno, Madeleine Albright, Judith Rodin and Carly Fiorina, the 90s saw the first woman attorney general, secretary of state, president of an Ivy League institution (University of Pennsylvania), and CEO of a Fortune 100 company (Hewlett-Packard). More women won political office than ever before in 1992, the so-called Year of the Woman, when their numbers in the Senate tripled (from a measly two to a small but more respectable six).

Cultural feminism in the 90s made strides, as well. The “Girl Power” movement promised that progress for women would trickle down to girls, too. Indie subcultures defined by girl-made zines, music, art and websites flourished, providing young women new platforms for self-expression. Girl culture was reclaimed and celebrated by the Riot Grrrl movement, Sassy magazine, websites like gURL.com, government initiatives, subversive feminist musicians and independent films.

By the end of the decade, however, the promise of equality for women was revealed to be something between a false hope and a cruel hoax. Parity, it turned out, was paradox: The more women assumed power, the more power was taken from them through a noxious popular culture that celebrated outright hostility toward women and commercialized their sexuality and insecurity. Feminist movements were co-opted. Soon, women would author their own sexual objectification.

I call what was done to women in the 90s bitchification, and it coincided with a radical new media landscape. The emerging 24-hour news cycle — providing real-time, unremitting coverage of live and current events — swiftly infiltrated households and shaped the American consciousness during and after the Persian Gulf War.

This continuous, addictive format produced an unrelenting fixation on public figures and news makers, but none so much as the women gaining power and prominence in the 90s. When any woman made the news, she often stayed there for days, weeks, months, and, in some cases, years. Meanwhile, news consumers blamed women for their own unceasing visibility, as if they had narcissistically engineered unflattering coverage of themselves for personal gain. The compulsive focus on scandal-driven tales pitching women out front and center, or against one another, gave new meaning to the old adage “If it bleeds, it leads.”

In the end, the 1990s didn’t advance women and girls; rather, the decade was marked by a shocking, accelerating effort to subordinate them. As women gained power, or simply showed up in public, society pushed back by reducing them to gruesome sexual fantasies and misogynistic stereotypes. Women’s careers, clothes, bodies, and families were skewered. Nothing was offlimits. The trailblazing women of the 90s were excoriated by a deeply sexist society. That’s why we remember them as bitches, not victims of sexism.

The 90s bitch bias is so pervasive, so woven through every aspect of the 90s narrative, that it can actually be tough to spot. Stories of notable women in the 90s almost invariably suggest they were sluts, whores, trash, prudes, “erotomaniacs,” sycophants, idiots, frauds, emasculators, nutcrackers and succubi. These disparagements were so embedded in the cultural dialogue about women that many of us have never stopped to question them. I spoke with more than a hundred women about their remembrances of the 90s, and the majority of them internalized 90s bitchification, too. The stories of 90s women have become sexist mythology, an erroneous history that saps women of their power, just as it was intended to do. Indeed, the aftershocks of 90s bitchification ripple into contemporary society. Discrediting women based solely on their gender, sexually harassing them and reducing them to their sexuality endures today from the school yard to the boardroom in part because this was, writ large, ubiquitous and accepted behavior in the 90s.

I loved my 90s childhood. But it wasn’t until returning to this decade as an adult that I came to see how mainstream 90s narratives in media and society promoted sexism and exploited girlhood. I was utterly shocked by what I found while investigating 90s narratives about women. The decade is barely considered history. It was supposed to be the modern era, with doors flung open to unprecedented advancement for women and gender equality. But 90s bitchification was like water flowing into every crevice. It existed everywhere I looked. Taken together, these stories explain the status of women in American society today.

Excerpted from 90s Bitch: Media, Culture, and the Failed Promise of Gender Equality (Harper Perennial, 2018).

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com