President Donald Trump is considering pardoning Muhammad Ali, the legendary boxer who died in 2016 at the age of 74.

Ali, born Cassius Clay, is best known today as one of the greatest athletes to ever step foot inside a boxing ring. But he was also an outspoken activist whose conscientious objection to serving in the Vietnam War would see him lose the heavyweight title and be effectively barred from his sport for over three years.

“I can’t take part in nothing,” Ali later said of his decision, “where I’d help the shooting of dark Asiatic people, who haven’t lynched me, deprived me of my freedom, justice and equality, or assassinated my leaders.”

In 1967, Ali was convicted of draft evasion, sentenced to five years in prison and fined $10,000. However, he remained free while he appealed his case. The Supreme Court in 1971 unanimously overturned Ali’s conviction, which leaves unclear whether a pardon is necessary or even possible. “There is no conviction from which a pardon is needed,” the late Ali’s attorney said in a statement Friday.

Trump pardoning Ali would be a break from his posture toward modern-day athletes who make their political opinions known on and off the field. The President has been particularly critical of National Football League players who have knelt during the national anthem to protest racism and police violence. (Trump also recently pardoned late boxer Jack Johnson, who was convicted on what many saw as racist grounds.)

Trump himself never served in Vietnam, having received several deferments for education and medical reasons.

Here’s more on the history of Ali’s conscientious objection, from TIME’s obituary written by Sean Gregory:

He would lose much more — the prime years of his career. In January 1964, Ali took the military qualifying examination. But his mental aptitude score was below the minimum requirement to be drafted. “I said I was the greatest, not the smartest,” he quipped. With the Vietnam War escalating, however, the military lowered the minimums. So in February of 1966, Ali was reclassified 1-A. His request for a deferment would be denied. When reporters hounded him for his reaction, Ali uttered words that would make him a national pariah, while at the same framed the debate about America’s role in the Vietnam conflict. “Man, I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong.”

Ali voiced his contempt for American policy before the anti-war movement gained steam. Newspaper editorial writers called Ali “the most disgusting character in memory to appear on the sports scene” and the “bum of all time.” The governor of Illinois labeled Ali as “disgusting,” while the governor of Maine said Ali “should be held in utter contempt by every patriotic American.” Ali next fight, against Ernie Terrell, was scheduled for Chicago in late March of 1966, but the Chicago Tribune urged the Illinois State Athletic Commission to cancel the bout. The state caved to the political pressure, and few other cities wanted any part of Ali: the Terrell fight was eventually moved to Toronto, though by this point Terrell himself backed out (a Canadian, George Chuvalo, filled in and actually went the distance with Ali before losing a one-sided decision). Media and politicians called for a boycott of the fight. “The heavyweight champion of the world turns my stomach,” said Frank Clark, a congressman from Pennsylvania.

By refusing to join the military, Ali was costing himself millions in endorsement money. Still, he didn’t flinch. “The white man want me hugging on a white women, or endorsing some whiskey, or some skin bleach, lightening the skin when I’m promoting black as best,” Ali told Sports Illustrated in 1966. “They want me advertising all this stuff that’d make me rich but hurt so many others. But by me sacrificing a little wealth I’m helping so many others. Little children can come by and meet the champ. Little kids in the alleys and slums of Florida and New York, they can come and see me where they never could walk up on Patterson and Liston. Can’t see them n—–s when they come to town! So the white man see the power in this. He see that I’m getting away with the Army backing offa me . . .They see who’s not flying the flag, not going in the Army; we get more respect.”

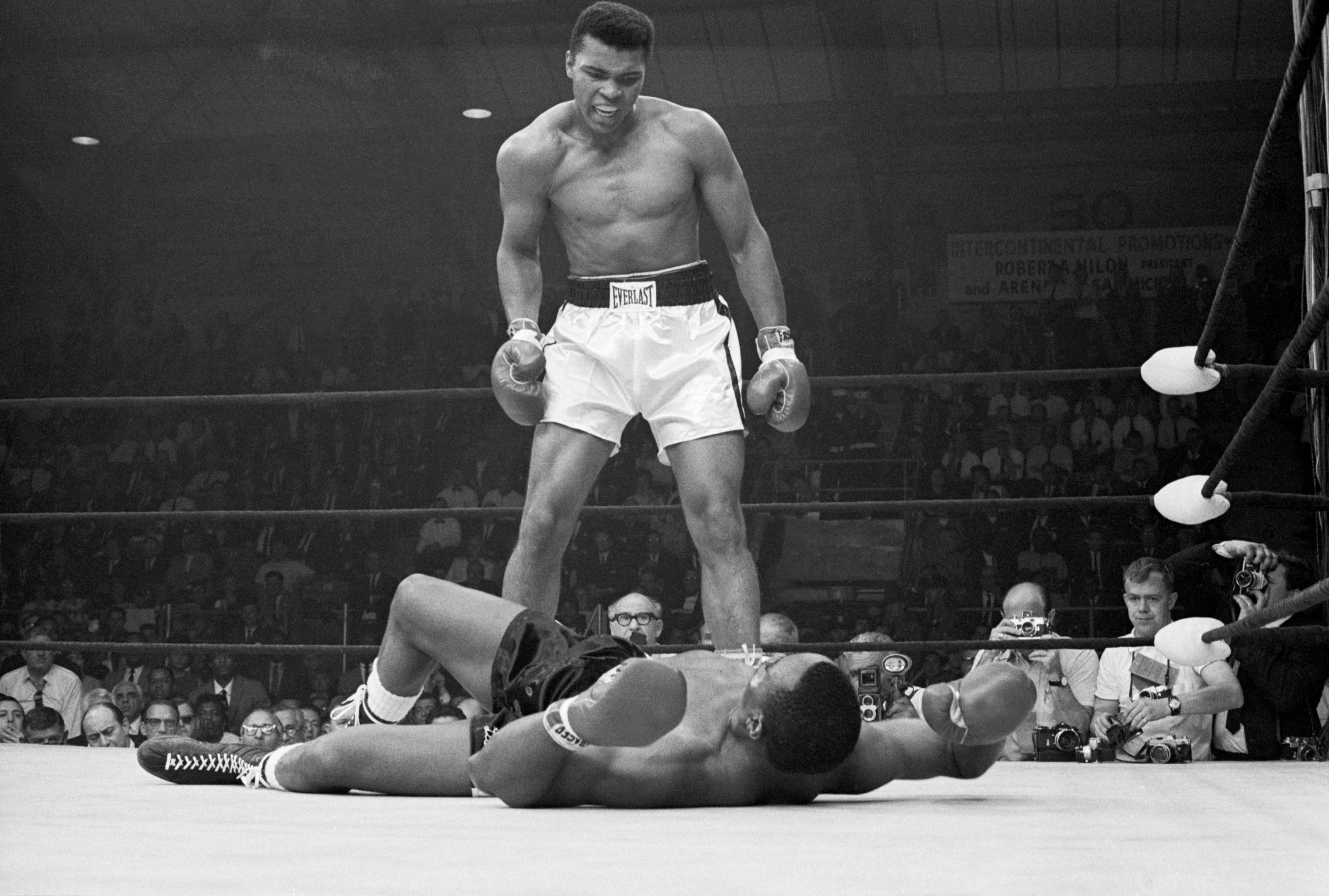

Ali filed for status as a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War, on the grounds that his religion prevented him from “participating in wars on the side of nonbelievers, and this is a Christian country, not a Muslim country. We are not, according to the Holy Qur’an, to even as much as aid in passing a cup of water to the wounded.” His conscientious objector claim bounced around the court system until April 28th, 1967, when Ali was to be inducted into the U.S. Army, in Houston. When the name “Cassius Marcellus Clay” was called out at the induction hearing, Ali refused to step forward. Ali was now facing a give-year prison sentence. He was immediately stripped of his titles and boxing licenses: Ali, 25, would not fight for another three-and-a-half years. “I can’t take part in nothing,” he’d later say, “where I’d help the shooting of dark Asiatic people, who haven’t lynched me, deprived me of my freedom, justice and equality, or assassinated my leaders.”

Exile – And Return

In June of 1967, Ali was convicted of draft evasion and given a five-year sentence. Though the appeals process kept him out of jail, no one let him back in the ring. “I canvassed 27 states tying to get him a license to fight,” Howard Conrad, one of Ali’s promoters, told TIME years later. “I even tried to set up a fight in a bullring across the border from San Diego, and they wouldn’t let him leave the country. Overnight he became a n—-r again. He threw his life away on one toss of the dice for something he believed in. Not many folks do that.”

While Ali was in exile, the man who struggled with reading, who finished ranked near the bottom of his high school class, made $2,500 a pop lecturing on college campuses (he also tried his hand at a Broadway musical, and received surprisingly positive reviews). “We’ve been brainwashed,” Ali said in one speech. “Everything good is supposed to be white. We look at Jesus, and we see a white with blond hair and blue eyes. Now, I’m sure there’s a heaven in the sky and colored folks die and go to heaven. Where are the colored angels? They must be in the kitchen preparing milk and honey. We look at Miss America, we see white. We look at Miss World, we see white. We look at Miss Universe, we see white. Even Tarzan, the king of the jungle in black Africa, he’s white. White Owl Cigars. White Swan soap. White Cloud tissue paper, White Rain hair rinse, White Tornado floor wax. All the good cowboys ride the white horses and wear white hats. Angel food cake is the white cake, but the devils food cake is chocolate. When are we going to wake up as a people and end the lie that white is better than black?”

As the 1960s drew to a close, Americans turned against the Vietnam War, elevating Ali’s popularity. And during an era when the government was giving false scores when it came to Vietnam, people knew that Ali was spouting truths, as he saw them. You might not agree with him, but you respected him. “I think Muhammad’s actions contributed enormously to the debate about whether the United States should be in Vietnam and galvanized some of his admirers to join the protests against the war for the first time,” the late Sen. Edward Kennedy told Hauser. “I respect the fact that he never backed down from his beliefs, that he took the consequences of refusing induction, and endured the loss of his title until after his conviction was reversed.” Ali told The Mirror newspaper of Great Britain, during a 2001 interview: “My refusal to go to Vietnam did not just help the black people, it helped more white people. More whites rebelled against Nam. It made me a hero to many white people as well as black people because I had the nerve to challenge the system, and all the people who hate injustice backed me for that.”

With Ali’s stature as a political and social force growing, the time was ripe to reassert his greatness in the ring. Since Georgia had no state boxing bureaucracy, Ali was able to secure his first fight in Atlanta, the deep South, against Jerry Quarry, a white man, on October 26, 1970. In the build up to the fight, Ali himself shied away from the anti-white rhetoric he sometimes employed at the height of his Nation of Islam allegiance. But he knew the fight had social consequences.

The Rev. Jesse Jackson, who was hanging around Ali’s camp in suburban Atlanta the day of the fight, laid them out for author George Plimpton, who was on assignment for Sports Illustrated: “If Cassius loses tonight, [vice president Spiro] Agnew could hold a news conference tomorrow,” Jackson said. “Symbolically, it would suggest that the forces of blind patriotism are right, that dissent is wrong, that protest means you don’t love the country . . . They tried to railroad him. They refused to believe his testimony about his convictions and his religion. They wouldn’t let him practice his profession. They tried to break his spirit and his body. Martin Luther King has a song:‘Truth crushed to the earth will rise again.’ That’s the black ethos. With Cassius Clay all we had was the hope, the psychological longing for his return. And it happened! In Georgia, of all places, and against a white man . . .So there are tremendous social implications. It doesn’t mean Quarry is a villain. But the focus has to be on Clay. He’s a hero, and he carries the same mantle that Joe Louis did against Max Schmeling, or Jesse Owens when he ran in Hitler’s Berlin. Injustice! In Atlanta, I have never sensed such electricity, such expectation in the streets. For the downtrodden, they need the high example – that their representatives, the symbol of their own difficulties, will win. Is that illogical?”

Quarry was gone in the third round. Ali’s fight style changed when he returned to the ring. His hands got soft, so he had to numb them before he got in the ring. Ali developed some fat, but his muscles were broader as well. With the time off, his legs weakened a bit. So he was no longer quick enough to dodge most punches thrown at him. “When he lost his legs, he lost his first line of defense,” Ferdie Pacheco, Ali’s long-time fight doctor, said in Muhammad Ali: His Life And Times. “That was when he discovered something which was both very good and very bad. Very bad in that it led to the physical damage he suffered later in his career; very good in that is eventually got him back the championship. He discovered he could take a punch.”

While Ali was suspended, a young heavyweight from Philadelphia, like Ali a former Olympic champion, claimed Ali’s crown: Joe Frazier. Ali wanted a title bout with Smokin’ Joe. A federal court ruled that New York’s denial of a ring license to Ali was “arbitrary and unreasonable,” since Ali’s lawyers gave the court a list of ninety convicted murderers, rapists, sodomites, armed thieves, and other miscreants who had been allowed to fight in the state. So six weeks after the Quarry fight, Ali returned to New York City in December, and survived a punishing fight against Oscar Bonavena, whom he finally beat in the 15th round. The stage was now set: Ali-Frazier, March 8, 1971, New York City, Madison Square Garden, Broadway. Ali was about to embark on the second act of a fight career that, given its captivating effect on the world — from the Americas, to Africa to the furthest reaches of Asia — would somehow exceed the first.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com