As the country mourns the loss of Arizona Sen. John McCain, there is one group for whom his death hits particularly close to home: the U.S. veterans who were Prisoners of War with him in the Hanoi prison where he spent the most difficult chapter of his life.

For this group, McCain’s death not only represents the loss of a respected public figure, but also of another one of their peers. Someone who, like them, was profoundly shaped by the traumatic experience of being detained in the notorious Hanoi prison, and the trials and tribulations that came with it.

“He was a dear friend; I loved him like a brother,” said Orson Swindle, who shared a cell with McCain during his captivity. “We came home [from Vietnam] and we had a long friendship.”

“We had our differences,” Swindle recalled with a chuckle. “On many occasions we’d fight and argue and then 10 minutes later be laughing about it.”

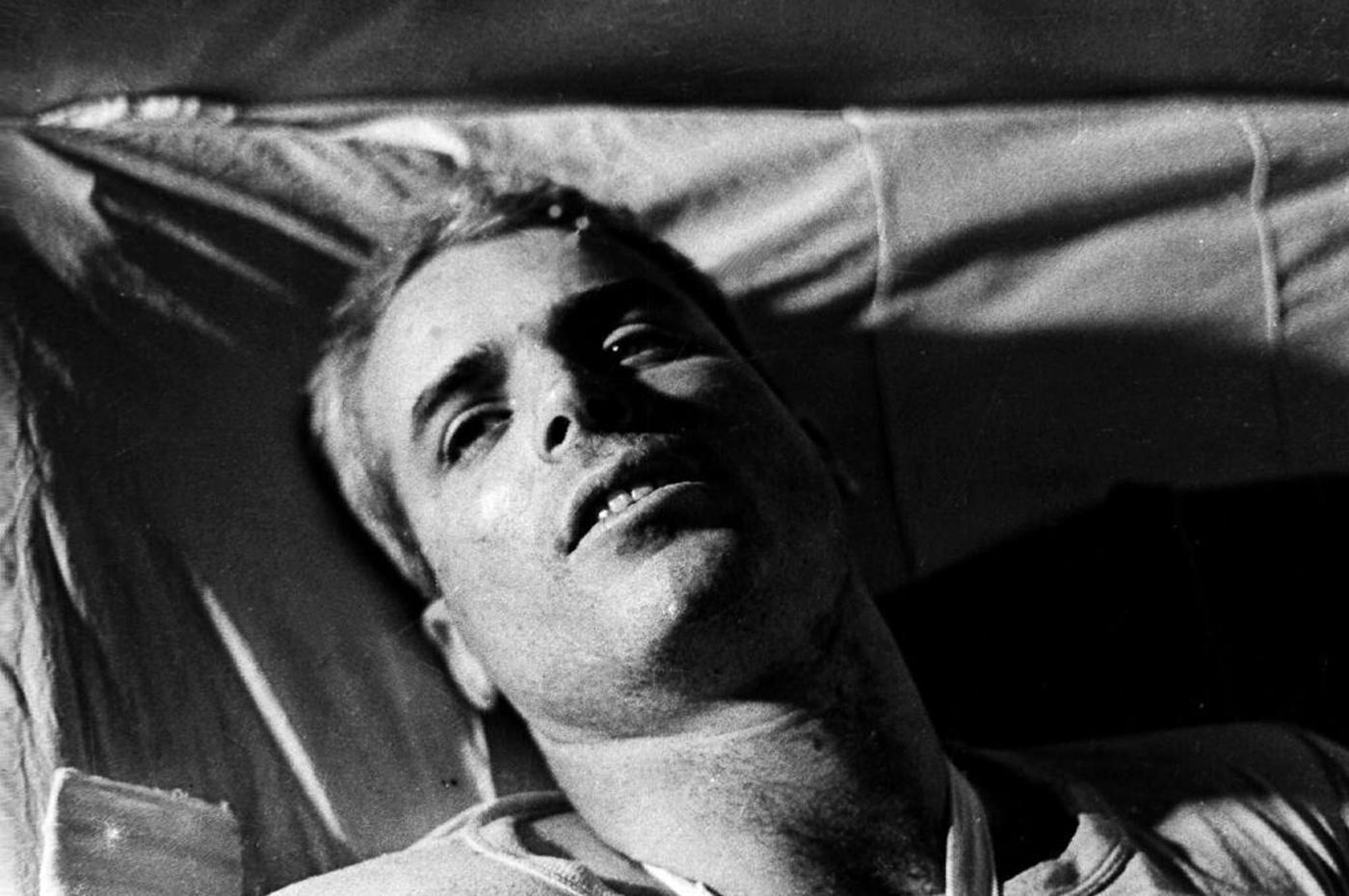

McCain’s story as a prisoner of war is well documented. A graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy and the son of a four-star admiral, McCain’s plane was shot down in October of 1967 over Hanoi, just one year before his father would become commander of all U.S. Vietnam forces. He was brought to the city’s infamous Hoa Lo prison — sarcastically referred to as “the Hilton” by its occupants — where he would spend the next five-and-a-half years. He was offered unconditional release a year into his imprisonment, but refused the offer because he did not want to jump ahead of his fellow soldiers who had been there longer. He subsequently spent two years in solitary confinement, where he was tortured at least twice a week by Vietnamese authorities seeking information about the U.S. At one point, he nearly committed suicide after he signed a confession.

Several veterans who were in the prison with McCain spoke with TIME in the months preceding his death, reflecting on McCain’s arrival at the prison, their shared experience and the way it molded McCain into a public figure defined by an independent streak with an ability to reach across the aisle.

The news of McCain’s imprisonment spread quickly throughout the Hilton, these veterans recall, because of his father’s military stature and the severity of his injuries. He had broken his right leg and both arms. His right arm was broken in three places, and he kept lapsing in and out of consciousness. The Vietnamese prison guards only took him to the hospital once they realized who his father was, and he was unable to walk for nearly six months.

“He came within a heartbeat of dying,” said Paul Galanti, who was in an adjacent cell to McCain in the prison. “He was put in a full plaster body cast and he couldn’t take it off for six months. His body just was becoming unglued.”

For all the POWs, it was McCain’s sense of humor despite these setbacks that stuck out. Once he was ambulatory, and released from solitary confinement, he, along with the other soldiers in the prison would amuse themselves by acting out movies. This was the only thing that remotely resembled some semblance of entertainment and normalcy, and McCain took great pleasure in it, whether he was the actor or the audience.

“We were crouched in the dark or dull light often in conditions of climate that were either hot or cold, but we were together. For many of us this was something — to be able to interact freely with other human beings,” said Major General John Borling, a career Air Force officer who spent six years in the prison. “This was our attempt to stay sane stay competitive, stay reinforcing one to another. John was highly contributory to that.”

But some of the POWs who worked with McCain once he entered politics said it was in the prison that McCain really discovered his passion for public service. When everyone was discussing what they would do once they were freed, Everett Alvarez Jr., a former Naval Officer who spent over eight years in Hanoi, recalled that McCain just wanted to read the news and study up on current events.

“His desire was molded of course [to run for office] when he was there,” he said. “His loss of freedom — it made us appreciate our country and what our country stands for.”

Once he entered public service, however, McCain became a bit removed from the people who shared the experience behind his journey into politics. After their release, the group of prisoners began convening annually for reunions that still happen today. While McCain was a prominent figure at those reunions in the early years, his presence gradually decreased as his public figure rose following his first election to Congress in 1982.

“He was always the emcee for our reunion until he got into politics,” Galanti, who still attends these reunions every year, said of McCain. “He didn’t come to a bunch after he got elected, particularly to the Senate, because everything he said could be used on the front page the next day, and so he just stopped telling jokes.”

But, Galanti recalled, when McCain did appear at gatherings, it was always a treat. “Every once in a while, I would get a call from a scheduler saying ‘John wants to get together with you guys,’ and we would all show up at the mainstream station and …have a bunch of beers,” Galanti said. “He was the old John.”

And these POWs remained loyal to their fellow soldier. Galanti had chairmanship roles in both of McCain’s presidential campaigns. After misinformation was circulated on the internet about McCain’s time in the Hanoi during his candidacy in 2008, Swindle helped lead the campaign’s “Truth Squad” team to set the record straight. Alvarez traveled with McCain during his first presidential bid in 2000, and during his first run for Congress. He also worked with him closely on veterans issues in the 1980s when when McCain was in Congress and he was working in the Veterans Affairs department. McCain wrote the forward to Borling’s book about his experiences in the Hanoi prison.

And all of McCain’s former prison-mates were quick to caution that, despite their political support for McCain, they didn’t always agree with everything he did. But, they said, their belief in his public service was reinforced by the confidence that he was acting to advance U.S. democracy — a core belief that was undoubtedly shaped in the isolation of Hanoi and is sure to be a key tenet of the late Senator’s legacy for years to come.

“When push comes to shove not only [did] he have my back and I’ve got his, but he’s got the back of the country in mind,” said Borling.

“I’ve always regarded him as a great American citizen,” he added. “America’s better for his presence.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Alana Abramson at Alana.Abramson@time.com