On a Thursday in January at Hollywood’s Dolby Theatre, an amateur singer has just nailed his audition. Singing “Maybe This Time”–the heartfelt number from Cabaret made famous by Liza Minnelli–a somewhat timid young man blasted through each note, and conjured up from nowhere a sense of yearning and desperation.

The three judges who hold the keys to his fate–pop star Katy Perry, country singer Luke Bryan and R&B legend Lionel Richie–are uncharacteristically exuberant. They’ve been largely quiet on this last day of “Hollywood Week,” trying to decide who will make the final slate of competitors, but now they burst into applause. Perry is moved to strip off her jacket and toss her chair from the judges’ dais into the crowd. Like the best moments from this show’s history, it’s both real and artificial. Moments later, once our aspiring star has walked offstage, a stagehand gingerly passes Perry her chair back.

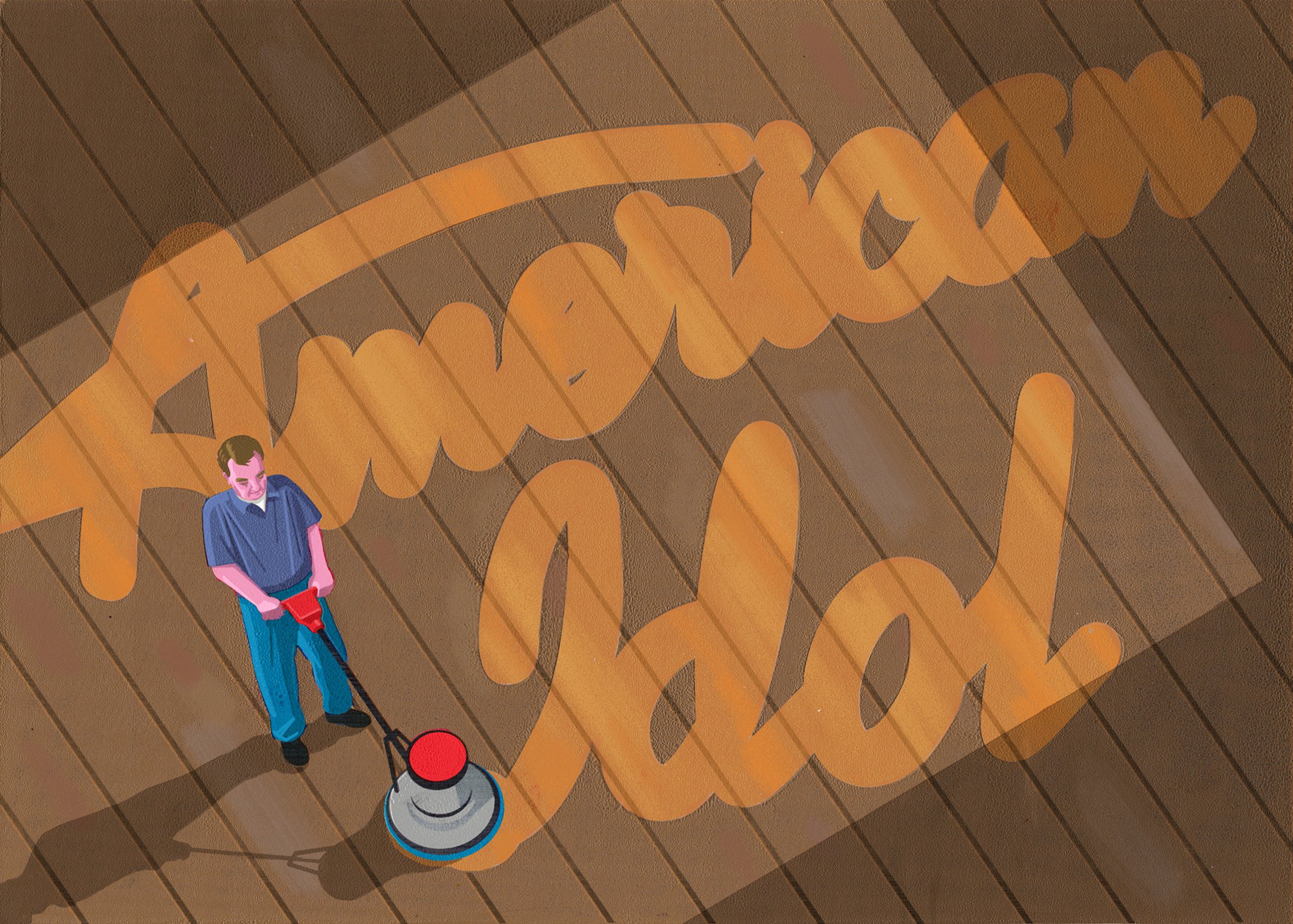

Welcome to the new, kinder, cuddlier American Idol. After a two-year absence, the show returns to prime time on ABC on March 11. The network hopes that it will do some version of what its first iteration did on Fox. Idol 1.0 was the nation’s defining reality-TV sensation, a show so popular at its height that other networks barely programmed against it. It generated A-list singers like Kelly Clarkson, Carrie Underwood, Jennifer Hudson and Adam Lambert, and made a household name of Simon Cowell, the brusque British record executive who cheerfully shattered auditioners’ dreams.

But even before American Idol left Fox in 2016, much of the world had moved on. The show was outpaced both by the amiable bickering on NBC’s music competition The Voice and by a changing entertainment ecosystem in which families—American Idol‘s natural audience—split into different audience segments. The family that, when American Idol debuted less than a year after 9/11, would have watched a fun singing competition together is now inhabiting different rooms, with Mom and Dad streaming a dark drama on Netflix while their son watches Logan Paul videos on YouTube and their daughter monitors her Instagram Stories.

How to knit an audience back together? Idol 2.0 meets a crasser, nastier era–one in which a former reality-TV star’s blunt judgments on social media make news every day. Yet Idol 2.0 says goodbye to the remnants of nasty quips from the judging panel, and hello to a newly inclusive suite of contestants and a nurturing, artist-friendly philosophy. Can a show with the last bit of bitterness leached out really thrive in 2018? “Reality TV tends to be strong when there’s a lot of cattiness and negativity,” Perry tells TIME, “and we don’t have a lot of that! So I don’t know!” In an era in which gentle, affirming communication seems in short supply, this Idol may end up hitting just the right note.

American Idol‘s first season, in 2002, was an instant hit thanks in large part to its sunny optimism and vision of heartland America as a wellspring of untapped talent. Alone among a reality-TV wave that included dark Machiavellian visions like Survivor and Big Brother, it seemed to reward pure talent, and placed the power in the hands of viewers voting from home. But the audience’s interest eventually waned. A long string of so-called white guys with guitars, winning year after year with only slight variations on the same act, ate into the show’s credibility as a star factory. In 2016, Fox canceled it.

And yet it’s already back. “It felt like there would be a place and a home for it,” says Ryan Seacrest, who has hosted every season and is returning for the new iteration. (News of sexual-abuse allegations made by Seacrest’s former stylist broke on Feb. 26.) The show had an eventually broken eight-year streak as America’s most-watched series; its final season came in at No. 19. Fox had hoped to keep American Idol on ice for a while longer; ABC, on the other hand, saw the show as part of a paradigm shift away from niche appeal. “I’ve been embracing the fact that we are a broadcast network,” says ABC president Channing Dungey. “The word broad is in the title.”

The new contestants grew up on American Idol; some were only babies when the show premiered in 2002. The show taught them how to sing in TV-ready increments, packing whole emotional arcs into two minutes or less. “Most of the contestants that really want to be on and really want to win, they are students of not only singing but of the show and how it works,” says Seacrest. “The best have that edge.”

The show taught its judges how to judge too. While the three panelists didn’t make their pronouncements during the final auditions–instead conferring among themselves ominously as to whom they would let through–their reactions revealed the personae each had been honing. Bryan was grave, his mouth set in a straight line no matter how high the note soared. Richie was smilingly, noddingly into it, no matter what “it” was. And Perry, who in conversation compares herself to Cowell (“He’s a real straight shooter, and I’m a real straight shooter; he has a sense of humor, and I have that same thing”) had mastered a virtuosic sort of performance that Cowell, ever the hater, couldn’t have dreamed of.

Perry describes her judging style as “a really nice balance [between] reality and fantasyland.” I observed her slow evolution during the 21st performance of the day, a rendition of Sam Smith’s “Too Good at Goodbyes.” Captured on the monitors producers use to watch footage, she was unsure, then warming, then pleasantly impressed, all before subtly indicating to stagehands that the mike volume be turned down just a tad.

The judges managed to evolve and keep their performances fresh even despite the repetitiousness of the day’s early going. What helped was the occasional dash of something that felt, well, un-Idol-y, in ways large and small. One contestant belted Aretha Franklin while wearing not the traditional American Idol sparkles but orange Converse sneakers. A young lady in a beret and white go-go boots sang an original song about “toxic masculinity.” (“Don’t forget, we love men of quality who believe in equality!” Perry exhorted before the song began.)

Some of the original Idol‘s uglier moments came in its desire to push past the inherent friendliness of its premise–as in the notorious “bad auditions,” in which inept singers were put in front of the judges. That had been phased out by the end of American Idol‘s first run and is excised now: “We are eliminating the borderline unstable people just to put them there and have a laugh at them,” says Trish Kinane, the show’s executive producer. Many of those bad singers at whom the show paused to laugh tended to be fey men. I Googled one of this season’s new singers–a tall, beehived chanteuse–only to find out that she was a drag queen (she sang “Natural Woman,” of course). That quite so many male singers the judges had brought a few rounds deep into the show’s new iteration seem to be comfortable covering their favorite divas suggested that American Idol has entered a new era. It’s still a show the whole family can watch, but for an era whose ideas of “the whole family” look broader than before.

Now that everyone has a platform, thanks to avenues to stardom like YouTube, SoundCloud and social media, the show may serve as more of an amplifier for stars who have already polished their act online. It will matter less, perhaps, who wins the vote than who dazzles enough to build their following, whose original song or edgy arrangement goes viral.

And American Idol can help educate digital-native kids who are gifted at packaging how to appeal to analog audiences. “We’ve encountered kids that do have a huge YouTube following already,” says Bryan. “But they feel like whether they go forward to the next round or not, it was an educational experience.” You can hit all the right notes in a YouTube video, but the act of being part of a production like American Idol, for a few days or for a season, will teach these contestants a bit more about how a business in upheaval works. As Richie puts it, “Consider us three master instructors. Hopefully, what we say has much more weight than an opinion from an executive.”

American Idol, which once made stars through sheer innovation, is now among the last establishment options still standing. Says Perry: “There aren’t as many gatekeepers, which means there’s more equality and availability to shine. But there are so many options–the market is so crowded.” This show, at its best, can cut through the clutter.

On a second break, between the day’s 51st and 52nd performances, I get a sense of why the show, 16 years after its launch, might just find a meaningful second life. In the contestants’ lounge, the drag queen is idly making conversation with a bearded fellow in a denim vest and cowboy hat. It was a quiet moment, one that was nearly drowned out by the buzzing energy of dozens of wired singers. But it seemed to point to American Idol‘s possibilities in 2018–that the show might create a musical conversation that crosses boundaries, pleases multiple sensibilities and generates something we’ve lost in our dissonant age. That is, of course, the simplest and loveliest thing of all: the sound of harmony.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com