On Monday, the National Portrait Gallery unveiled portraits of Barack Obama and Michelle Obama painted by, respectively, Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald. The new paintings will be part of the exhibit America’s Presidents at the National Portrait Gallery, the only place outside the White House with a complete collection of presidential portraits from George Washington to Barack Obama.

The earliest presidential portraits sometimes served as the only images of the president. These days, it’s easier than ever for the White House to take and share photographs of the President on social media, but paintings like the Obamas’ portraits — images of which can be seen online, with the works on view to the public at the National Portrait Gallery starting on Tuesday — still offer another read on a president.

“Photographs are candids, but the portrait is a more careful, thoughtful, reading of a president and his personality,” Kate Lemay, a historian at the museum who curated the exhibition, told TIME.

The First Portrait

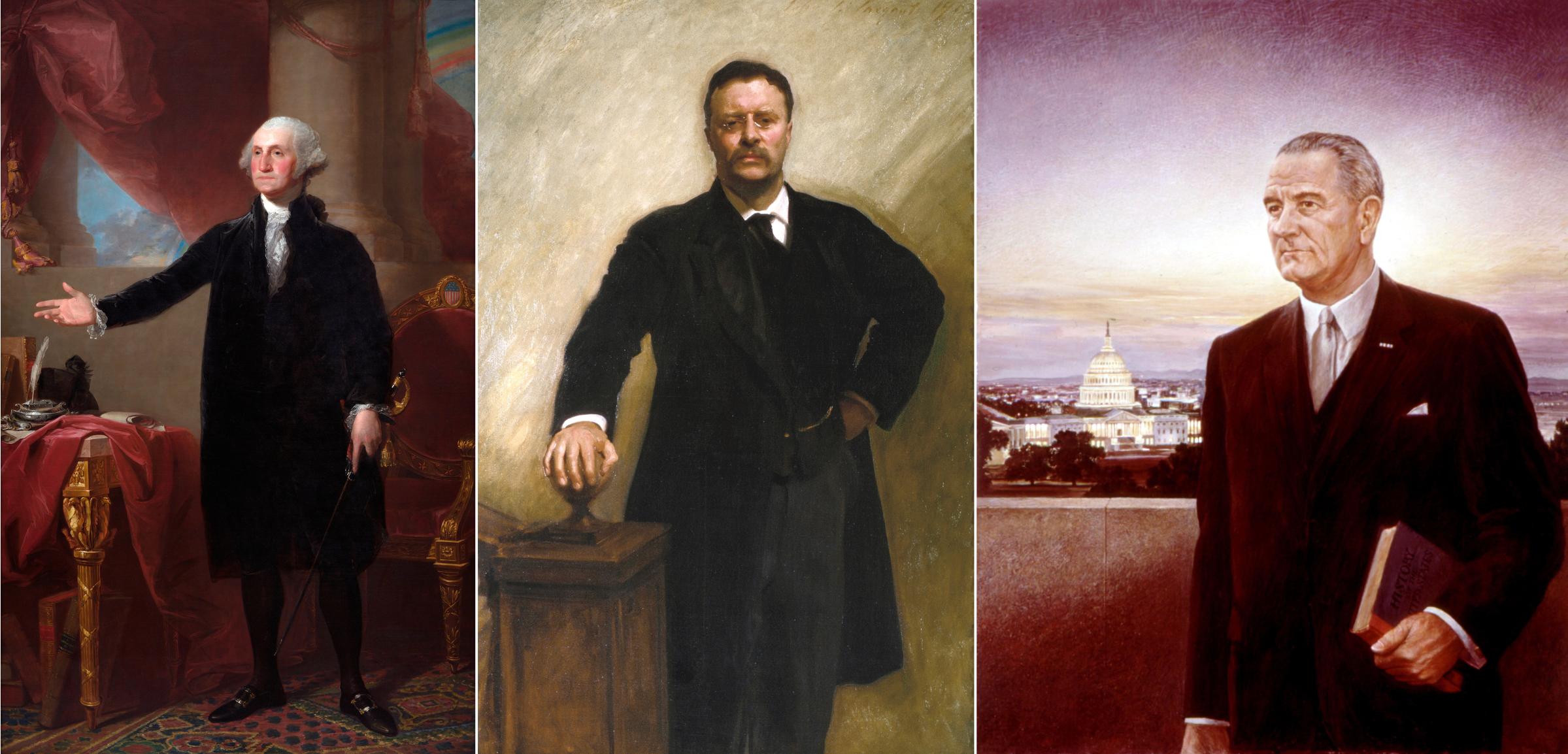

It’s almost certain that you’ve seen the portrait of George Washington that Gilbert Stuart painted in 1796. Versions of the portrait hang in the White House and the National Portrait Gallery, and you might also have a different Stuart depiction of Washington in your wallet, as he created the image that was the model for the Washington who appears on the $1 bill.

“The composition is often thought to evoke the moment when Washington addressed Congress in December 1795 in support of the Jay Treaty, which resolved lingering tensions between Britain and the United States,” according to the book that accompanies the American Presidents exhibit. “Pennsylvania Senator William Bingham and his wife, Anne, commissioned the painting in the spring of 1796 to celebrate the treaty and presented it to English statesman William Petty, first Marquess of Lansdowne, who as prime minister had negotiated the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783.”

Congress bought the painting, and President Adams placed it in the President’s House, where it was famously saved from potential ruin during the War of 1812.

Commissioning portraits of leaders and prominent society figures was one of the many European traditions that came across the pond when the U.S. was founded. But Stuart set an important precedent for future portraits of specifically American leaders, in terms of the composition. Though Washington holds a sword, as a nod to the President’s successful military career, Stuart made sure that his presentation didn’t make Washington look like a monarch or a military figure, “to set the precedent that the president is a man of the people, is elected by the people, so he [looks like he’s] part of the people,” according to Lemay.

As for First Ladies, though elite women would certainly have had their portraits painted before the 20th century, it wasn’t until around 1902, when Theodore Roosevelt’s First Lady Edith Roosevelt oversaw a renovation of the White House, that portraits of the First Ladies would start to be hung in the Vermeil Room on the ground floor of the White House.

Who Pays for Presidential Portraits

Through the early 20th century, the funds for official portraits mostly came from Congress, White House Historical Association curators said in a recent podcast. In more recent history, the money has come from private donations, usually raised by the National Portrait Gallery. (The White House Historical Association has also raised private funds for portraits, but that’s a separate operation.)

The National Portrait Gallery commissioning process used for the Obama portrait is fairly recent, and was only set up towards the end of George H.W. Bush’s term. Since then, the National Portrait Gallery has suggested contemporary artists, and the President will choose one, says Lemay.

Funding for First Ladies’ portraits wouldn’t exist until the 1960s, when First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy founded the White House Historical Association. Before that, First Ladies may have arranged to have their own portraits done, or like-minded interest groups would pay for them. For instance, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union paid for the portrait of Rutherford B. Hayes’s First Lady Lucy Hayes because she didn’t allow alcohol in the White House. The commissioning process set up for George H.W. Bush’s portrait has applied to First Ladies too, beginning with Hillary Clinton.

What Happens If the President Hates It

The Presidents generally pick the artist who’ll paint their official portraits, and many love the result. In fact, Andrew Jackson had a portraitist whom his late wife patronized, Ralph E.W. Earl, follow him around at all times.

But there are times when they have requested a do-over. Theodore Roosevelt “destroyed” Theobald Chartran’s portrait of him because he thought it made him look like a “mewing cat,” according to the book America’s Presidents: National Portrait Gallery. He then hired John Singer Sargent, who also had trouble getting the President to strike the right pose.

As the story goes, Roosevelt accused Sargent of not knowing what he wanted, then Sargent snapped back that the President didn’t know how to pose. Roosevelt placed his hand on the newel of a staircase he was about to ascend and said,” Don’t I!” Sargent told him not to move. “He needed to animate the President, and he did—by making him angry,” William Kloss, author of Art in the White House: A Nation’s Pride, explained in a recent podcast.

President Lyndon B. Johnson was not easy to work with, either. He called the first portrait that Peter Hurd did, depicting him standing outside with the Capitol in the background and holding a book entitled HISTORY, “the ugliest thing I ever saw,” while the First Lady thought that the artist didn’t do Johnson’s “gnarling, hardworking” hands justice. Hurd tried again at Camp David, and the President fell asleep. When Hurd seemed as if he didn’t have enough time, Johnson got on his nerves even more when he bragged that Norman Rockwell managed to paint him in 20 minutes, according to American Mirror, a biography of the artist. Hurd got back at him by giving the first attempt — the portrait that LBJ didn’t like — to the National Portrait Gallery, dissing the president as “damn rude” in an interview. In the end, Elizabeth Shoumattoff, the artist who painted FDR, would end up painting the 36th President’s official portrait in 1968.

Symbolic Meanings

Some of the official portraits also reveal things about Presidents’ characters and lives.

Artist George Peter Alexander Healy, who painted many presidents, depicted John Tyler holding crumpled piece of a D.C. newspaper that had praised the politics of Tyler’s rival Henry Clay. And Healy’s portrait of Abraham Lincoln, which came out of the artist’s Peacemakers series, depicted the president leaning forwarding as if he is “listening attentively to General Sherman’s urgings,” to illustrate the way he carefully listened to his advisers before rendering a verdict, as Kloss put it.

In 1963, Elaine de Kooning depicted President John F. Kennedy sitting awkwardly in a chair, bracing his back, though his back problems were not something visible to the American public. “She painted him as she saw him, a true to life moment, when he was physically uncomfortable,” Lemay says. “It’s a true to life moment. I think people just tend to forget that [Presidents] are human, with both physical flaws and character flaws.”

Similarly, artist Nelson Shanks offered a nod in his portrait of Bill Clinton to the Monica Lewinsky sex scandal that had dominated Clinton’s second term. The artist has said that the shadow on the left-hand side on the mantle in the Oval Office is supposed to represent the shadow that the scandal cast on his legacy. It was also specifically a reference to the dress owned by Lewinsky told became a central piece of evidence in the scandal, Shanks told The Guardian: “It actually literally represents a shadow from a blue dress that I had on a mannequin, that I had there while I was painting it, but not when he was there.” Maureen Dowd called Shanks’ effort “devilish punking.”

And then, there will be what we can deduce about the times that the President served in. Just as Obama’s election was ground-breaking, Kehinde Wiley’s portrait will “break new ground in the way presidents are portrayed,” Lemay predicts.

“Portraiture helps us understand history,” she says, “so 20 years from now, we’re going to be looking at Kehinde Wiley and have a real window into the very moment we’re living in.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com