Of all those with a stake in the release of the so-called Nunes memo, one of the most important has gone largely overlooked: the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court itself.

The FISA Court is a special, powerful tribunal of federal district judges, appointed by the Chief Justice of the United States. It is authorized by Congress to allow federal law enforcement officials to surveil U.S. citizens suspected of spying for, or otherwise assisting, hostile foreign powers. Because of the obvious sensitivity of its operations, the FISA Court largely conducts its proceedings in secret and relies solely on the government’s evidence as justification for invading the privacy of Americans.

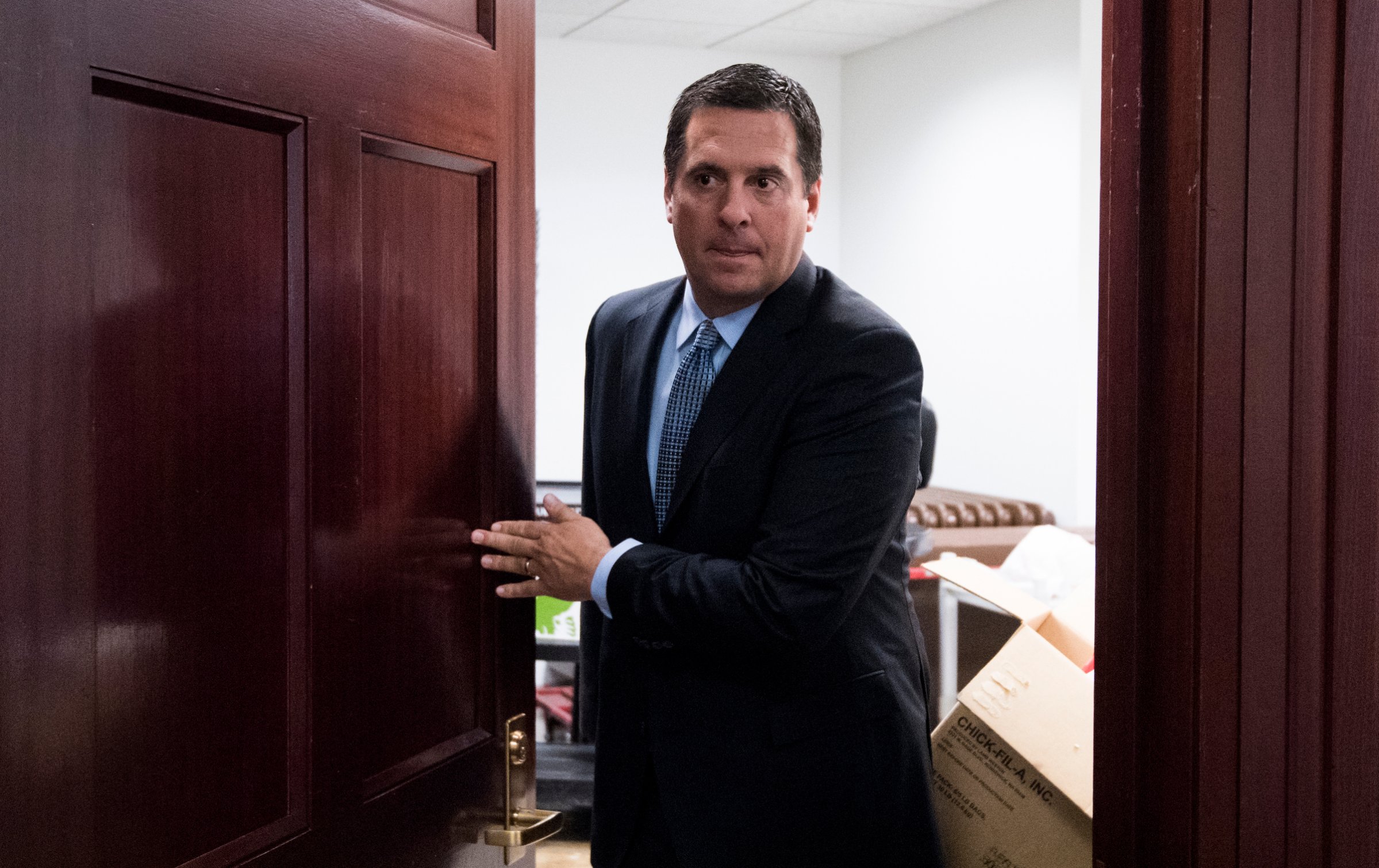

The Nunes memo questions “the legitimacy and legality of certain [Department of Justice] and FBI interactions” with the FISA Court and alleges “a troubling breakdown of legal processes established to safeguard the American people from abuses related to the FISA process.” In doing so, the Nunes Memo has directly attacked the legitimacy of the court.

The FISA Court has an institutional duty to protect the credibility of its decisions. It should publicly direct the Department of Justice to respond in court to the Nunes Memo: the American people need an independent and unbiased evaluation of the memo’s claims.

The rebuttal of the Nunes Memo prepared by the minority members on the House Intelligence Committee cannot divest itself of political associations, and only the FISA Court can order the government to take corrective measures, should any be necessary. In order to vindicate its own utility and purpose, the court needs to collect and review all pertinent facts, and then either publicly refute or validate the Committee’s allegations.

Some may question whether the FISA Court has the authority to enter the fray. It undoubtedly does. The Supreme Court has long recognized that the “public welfare demands that agencies of public justice be not so impotent that they must always be mute and helpless victims of deception and fraud.” Our constitutional tradition fully appreciates that “tampering with the administration of justice . . . is a wrong against the institutions set up to protect and safeguard the public, institutions in which fraud cannot complacently be tolerated consistently with the good order of society.”

Accordingly, the “inherent power of a federal court to investigate whether a judgment was obtained by fraud is beyond question.” And the statute creating the FISA Court even provides a mechanism for addressing the memo’s charges. The law empowers the FISA Court, “on its own initiative” to “hold a hearing or rehearing . . . upon a determination that . . . the proceeding involves a question of exceptional importance.”

The Nunes Memo surely raises “a question of exceptional importance.” It is not every day that the majority members of the House Intelligence Committee accuse DOJ and FBI officials of a political conspiracy against the President of the United States — a conspiracy involving a covert plan to surveil the electronic communications of a U.S. citizen for purely political motives. Nor is it common practice for the President of the United States to declassify such potentially destabilizing allegations for public consumption over the open and vigorous objections of top intelligence and law enforcement agents. The unavoidable disruption that these actions have jointly unleashed upon the U.S. intelligence and law enforcement communities, and the relationship of those institutions with the FISA Court, not to mention the public, are matters of “exceptional importance.”

Whether the FISA Court has the authority to initiate its own investigative proceedings, though, is a distinct question from whether it should. Some might argue that it would be inappropriate for the court to inject itself into a political dispute that has engulfed the country. They would say that courts must steer clear of partisan struggles or risk losing their powerful moral authority that derives from political independence. But under these circumstances, they would be mistaken.

The fundamental question raised by the Nunes Memo is not political; it is factual. Did DOJ and FBI officials mislead the FISA Court by withholding material information that would likely have affected the surveillance authorization for Carter Page? The answer to this question lies within the factual record that the FISA Court has either: (1) already gathered; or (2) can readily obtain through standard judicial inquiry. Courts are in the business of making such factual determinations: it’s their bread and butter. And we stake our entire judicial system on the assumption that federal judges do not exercise political bias when they adjudicate facts. Stated differently, the apprehension that factual findings may have political consequences should not be a judicial concern.

Arguing for the adoption of the Federal Constitution, Alexander Hamilton famously described the judiciary as the “least dangerous” branch of the federal government. Because they have “no influence over the sword or the purse; no direction either of the strength or of the wealth of society; and can take no active resolution whatever,” Hamilton concluded that the federal courts “have neither FORCE nor WILL, but merely judgment.” In retrospect, perhaps Hamilton was a bit coy. But throughout American history, the solid and independent judgment of the federal courts has repeatedly cooled the heat of partisan conflict. We could certainly use some good judgment now.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com