You wouldn’t know the significance of the small gravestone, tucked behind St. Pancras Old Church, London, if it weren’t for all the mud.

There’s a meter radius of mud surrounding the grave of Mary Wollstonecraft, the feminist thinker and author of The Vindication of the Rights of Woman, where visitors have tramped across the grass to get a better look. The stone itself isn’t much to look at; Wollstonecraft’s name is so worn by time it’s barely legible. But visitors haven’t made the pilgrimage just to pay their respects to Wollstonecraft. The grave is also at the center of a story of intrigue, morbidity and romance — and without it, there’d be no Frankenstein.

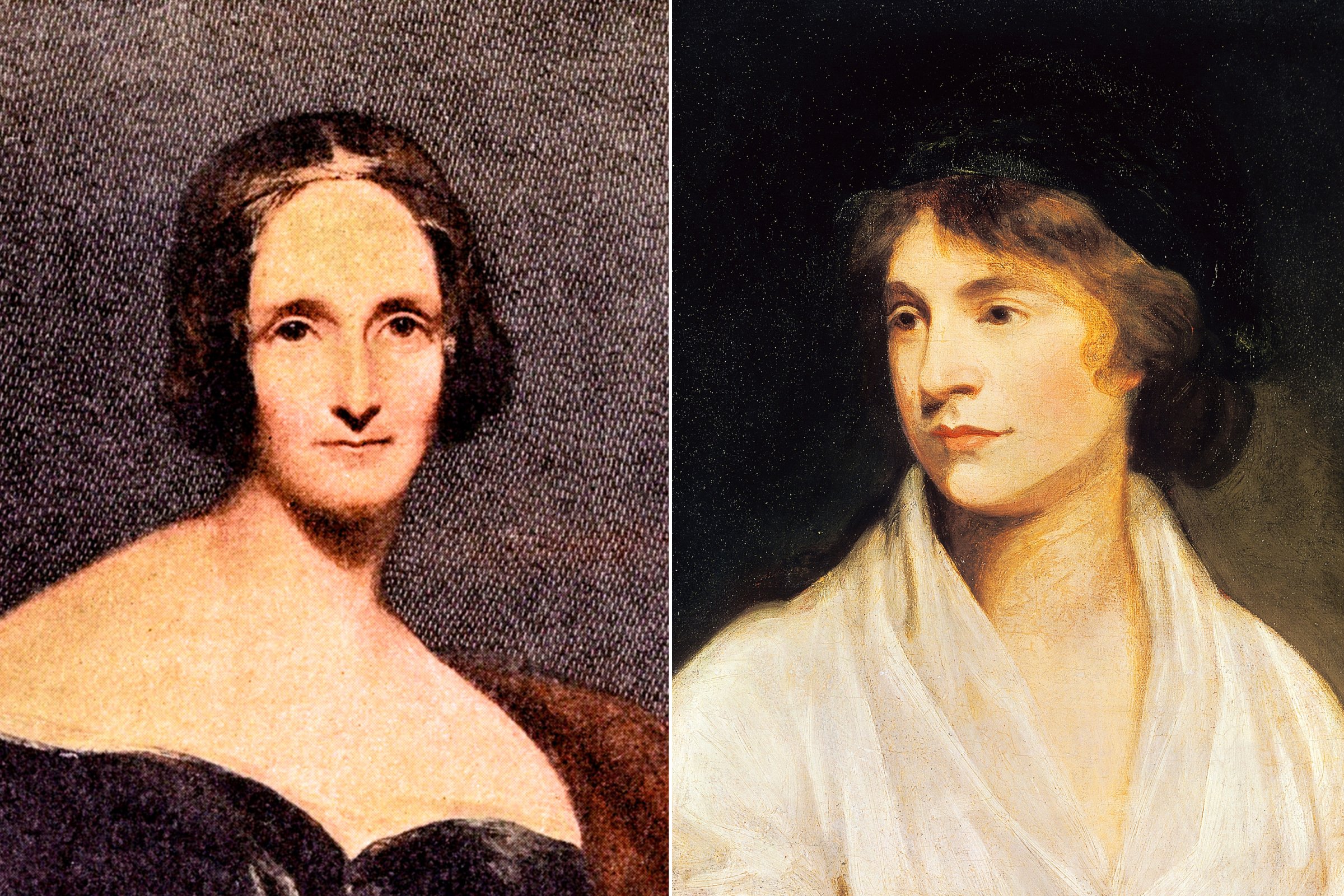

Wollstonecraft was the mother of Mary Shelley, the author of the famous horror story, published 200 years ago this year, about a monster brought to life by maverick scientist Victor Frankenstein. She did not live to see her daughter grow up to become a writer, dying of septicemia just over a week after giving birth to Mary. But even in death, Wollstonecraft played a pivotal role in Mary’s life.

Wollstonecraft was a radical thinker, vilified for her feminist ideas, and even called a “hyena in petticoats” by one British politician, Horace Walpole. She led an unconventional life. Her father was a drunk and she had an illegitimate child, a daughter called Fanny Imlay, before marrying Mary’s father, the famous philosopher William Godwin. And after their marriage, Godwin and Wollstonecraft preferred to live separately during the day and communicate by correspondence, exchanging notes and letters. In the run-up to Mary’s birth in 1797, Wollstonecraft sent a note to Godwin as she waited for the midwife, eccentrically referring to Mary as their “animal”:

“I have no doubt of seeing the animal to day; but must wait for Mrs Blenkinsop to guess at the hour – I have sent for her – Pray send me the newspaper [sic].”

As a child, Mary was profoundly affected by her mother’s legacy, later writing in 1827: “The memory of my mother has always been the pride and delight of my life.” Mary’s father taught her to read by tracing the letters on Wollstonecraft’s gravestone, as mother and daughter shared the same first name.

“[Godwin] would not have thought this was macabre. He would have thought this was an excellent way to teach his daughter about her famous mother,” Charlotte Gordon, author of Romantic Outlaws: The Extraordinary Lives of Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley, tells TIME.

The graveyard became Mary’s private place, where she would often retreat. It was at Wollstonecraft’s grave that the teenage Mary first declared her love for the poet Percy Shelley. Shelley was an admirer of Mary’s father, and grew close to Mary during his frequent visits to the family house. She was 16; he was 21, and already married.

“Percy was impressed with how brave she was to break all the rules that bound conventional young women,” Gordon says.

Scholars like Gordon speculate that the graveyard was also where the couple first consummated their relationship. Mary referred to July 28, 1814, as the anniversary of their “union,” after which they ran away to Paris together. Godwin disowned his daughter for several years after the elopement, which devastated Mary.

In addition to her gravestone, Wollstonecraft left behind another tangible legacy: her literary works. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, published in 1792, was a ground-breaking work that advocated, among other things, the reform of female education and a woman’s right to earn a living. Ahead of its time, the publication still resonates in feminism today. Her daughter read all of Wollstonecraft’s works several times, according to Gordon, later writing about the pressure she felt to match her mother’s talent. She grew up surrounded by her parents’ famous friends, including poet Samuel Coleridge. Mary’s taste was also similar to her mother’s; Wollstonecraft refers in letters to the influence of Milton’s Paradise Lost, which looms large in Frankenstein.

“Mary Shelley saw herself as the keeper of the Wollstonecraft flame, and dedicated her life to living according to her mother’s ideals and philosophy,” Gordon says. “We know she read all of her mother’s books because she kept carefully detailed lists of the books she read. For example, when she ran away with [Percy] Shelley, they kept a joint diary, and they recorded that they read aloud from Wollstonecraft on their journey and found inspiration from her words.”

Mary not only shared Wollstonecraft’s intellect and literary talent; both mother and daughter suffered from depression.

“Mary’s father was very concerned about his daughter’s dark moods, as he did not want her to be like her mother, who tried to kill herself twice,” Gordon says.

Mary’s dreams were haunted by the loss of her first daughter, born prematurely in 1815, according to her journal, while Wollstonecraft described in one of her published works how her “very soul diffused itself in the scene” around her following a suicide attempt. However, while Frankenstein is undoubtedly dark, the creation of Frankenstein’s Creature out of body parts, in an era where grave robbers were common, was to contemporary readers perhaps less macabre than one might expect.

“[Mary] would not have considered herself drawn to the macabre or to horror,” Gordon explains. “Instead, she would have said she was committed to exploring the deepest, darkest facets of the human soul – how we deal with loss, how we deal with sorrow, how we deal with death.”

Mary’s fascination with death and “the…darkest facets of the human soul” found its ultimate outlet in Frankenstein. In 1816, Lord Byron, a friend of the Shelleys, challenged the group staying with him at his rented villa in Geneva to each come up with a ghost story.

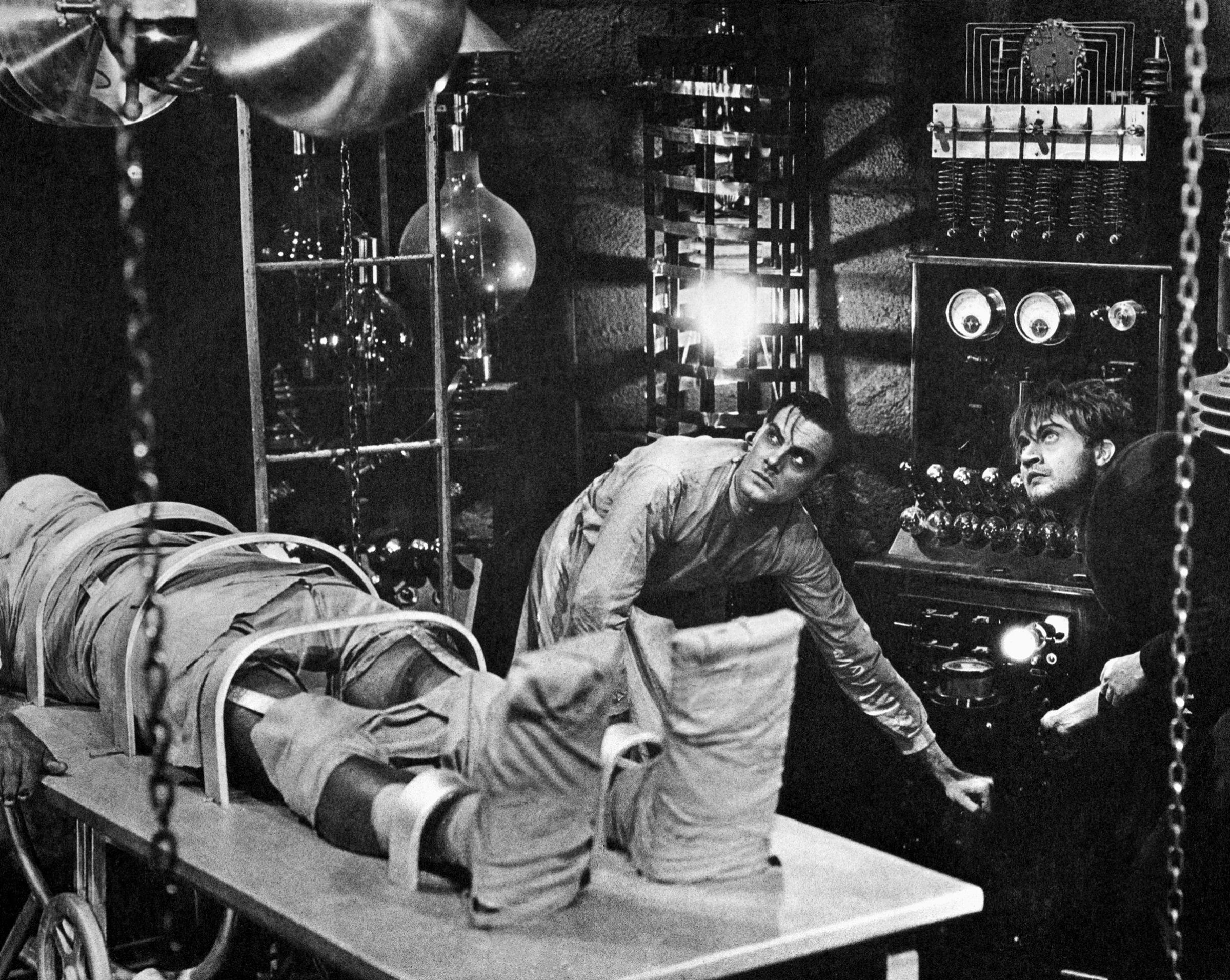

Mary Shelley’s story was born of a nightmare: “I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine show signs of life.” Mary then developed the short story into a novel at her husband’s urging.

She faced an onslaught of tragedy during the writing process of Frankenstein. Within a couple of months, Shelley’s pregnant first wife, Harriet, committed suicide, as did Mary’s half-sister Fanny. Mary was close to Fanny; both revered Wollstonecraft, and Fanny had previously “determined never to live to be a disgrace to such a mother [sic]”.

“In many ways, the Creature in Frankenstein is inspired by [Mary’s]… outrage at the sufferings of outcast women, starting with her mother’s terrible experiences as an unmarried mother,” Gordon says. “Just as the Creature is rejected by society, so were women who had children out of wedlock, or who were born out of wedlock, like her half-sister Fanny, who killed herself while Mary was writing the novel.”

Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus was published in 1818; by 1851 it had sold 7,000 copies, more than all of Percy Shelley’s poetry volumes combined. Today it remains one of the bestselling gothic novels of all time.

While the tale of Byron’s ghost story challenge is often cited as Frankenstein’s inspiration, the timeworn grave surrounded by mud in central London offers another touchstone. Wollstonecraft’s grave provided the focal point of Mary’s childhood and of her relationship with Shelley, and it ties together Mary’s lifelong obsessions with her mother’s legacy and the morbid.

Wollstonecraft, a radical dismissed after her death as a hysteric, never knew her daughter; but in Frankenstein, Mary provided her a lasting tribute.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com