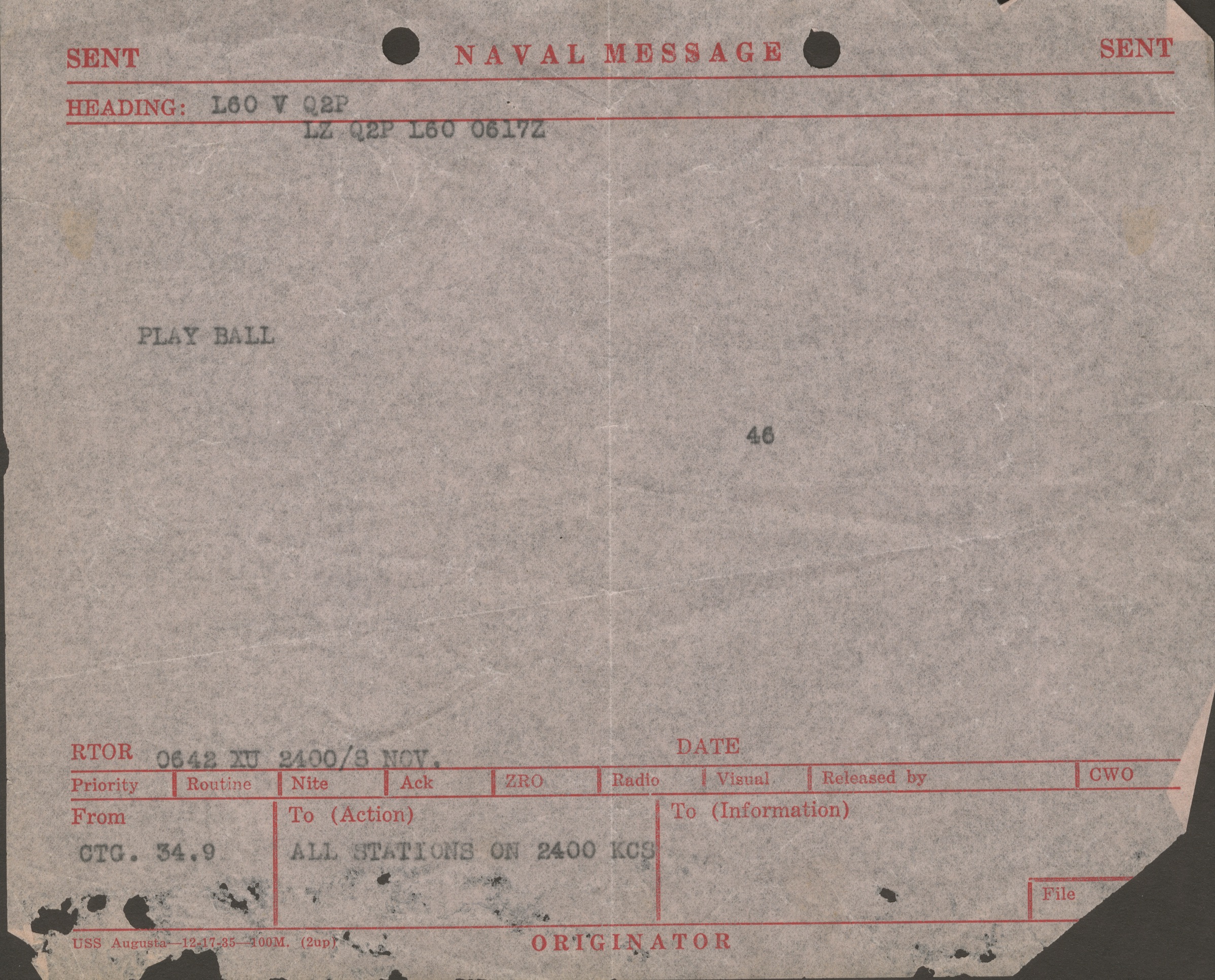

When the message was decoded, it was only two words long, and it could have referred to almost anything: PLAY BALL.

In the context, however, the meaning was clear — and more complex than its brevity would suggest. The recipient, after all, was Maj. Gen. George Patton, who was on a ship off the coast of Casablanca, waiting for word from Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, the future president and Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force. This message, from Eisenhower, was the go-ahead he needed to launch the invasion known as Operation Torch, which he did 75 years ago, on Nov. 8, 1942. With that, American forces were officially engaged in their first World War II combat in the war’s Europe and North Africa theater.

The decision to help the Allies concentrate on Germany first was not a foregone conclusion for the U.S., given the attack on Pearl Harbor, but it quickly paid dividends in North Africa. “The occupation of French North Africa had been accomplished with Blitzkrieg briefness, utilizing expert coordination of planes, ships, tanks, trucks, guns and courageous men. In spots it was easy. In others resistance was bitter, though brief,” TIME summarized in the aftermath:

In Morocco tough, muscular Major General George S. Patton Jr. ran into just the kind of opposition for which he had prepared. Months ago, on the deserts of southeastern California, he had drilled his men to fight in blazing heat over terrain such as they would meet in North Africa. Patton had insisted that they keep their sleeves rolled down, that they get along on a minimum of water. He had forbidden that vehicles, moving or standing, be within 50 yards of one another, lest they provide a bunched target. Not long after his men reached Africa, their grumbles turned to praise for what the Old Man had taught them.

Two nights before the U.S. struck, Hans Auer, German Consul General in Casablanca, had called a meeting of twelve Nazi armistice commissioners at the Hotel Plaza to warn them that an Allied invasion was imminent. De Gaullists followed the Germans, set up machine guns covering the hotel’s exits. When the meeting broke up, a blaze of gunfire silenced the Germans.

Though De Gaullist guns thus disrupted Nazi preparations, Casablanca still managed to put up the stiffest of all resistance to the U.S. invasion. Foresighted George Patton shoved three tank columns ashore east and west of the sprawling city and hit first for an outlying reservoir. With that in his hands, he could cripple Casablanca if necessary. Soon parachutists seized the city’s main airdrome and the tank force advanced.

Off Casablanca, U.S. warships commanded by Admiral Henry K. Hewitt knocked out a bitterly resisting French cruiser-destroyer force while Navy flyers bombed the 35,000-ton battleship Jean Bart into a blazing hulk. The U.S. fleet moved inshore and soon was heaving shell after shell into the Moroccan coast.

By the time Patton’s three tank columns had pierced through to Casablanca, all coastal French Morocco, from Agadir in the south to the Spanish Moroccan border on the north, was in American hands.

Said General Eisenhower succinctly: “I do not regard this as any great victory. I regard these people as our friends. We had a misunderstanding, but fortunately it ended in our favor. The job now is to get this thing organized and go after the enemy.”

The copy of the decoded message seen above will be on display starting Wednesday as part of the exhibition The Real and Reel Casablanca; American Troops Enter World War II, Landing in North Africa at the International Museum of World War II in Natick, Mass. It ended up in the collection, explains museum director Kenneth W. Rendell, via an aide to Patton. “Patton read it and handed it back to him, and said, ‘Save this, it’s an important souvenir,’” Rendell says. He did, and the the museum later acquired the message from his family.

This invasion was, Rendell says, “really the beginning of the Patton legend.” It was also the beginning of awareness, for many Americans, of where Casablanca was and what was going on in North Africa. That’s part of the reason why the movie Casablanca is also part of the story, as it was rushed to theaters within weeks of the invasion and helped inform American audiences at home, Rendell says, “showing people where their husbands and sons were fighting and what it was like there.”

Correction: The original version of this article incorrectly described the first overseas World War II combat by American troops. Americans first fought in the Pacific, not in North Africa. Operation Torch, in Casablanca, saw their first large-scale offensive involvement in the war’s Europe/North Africa campaigns.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com