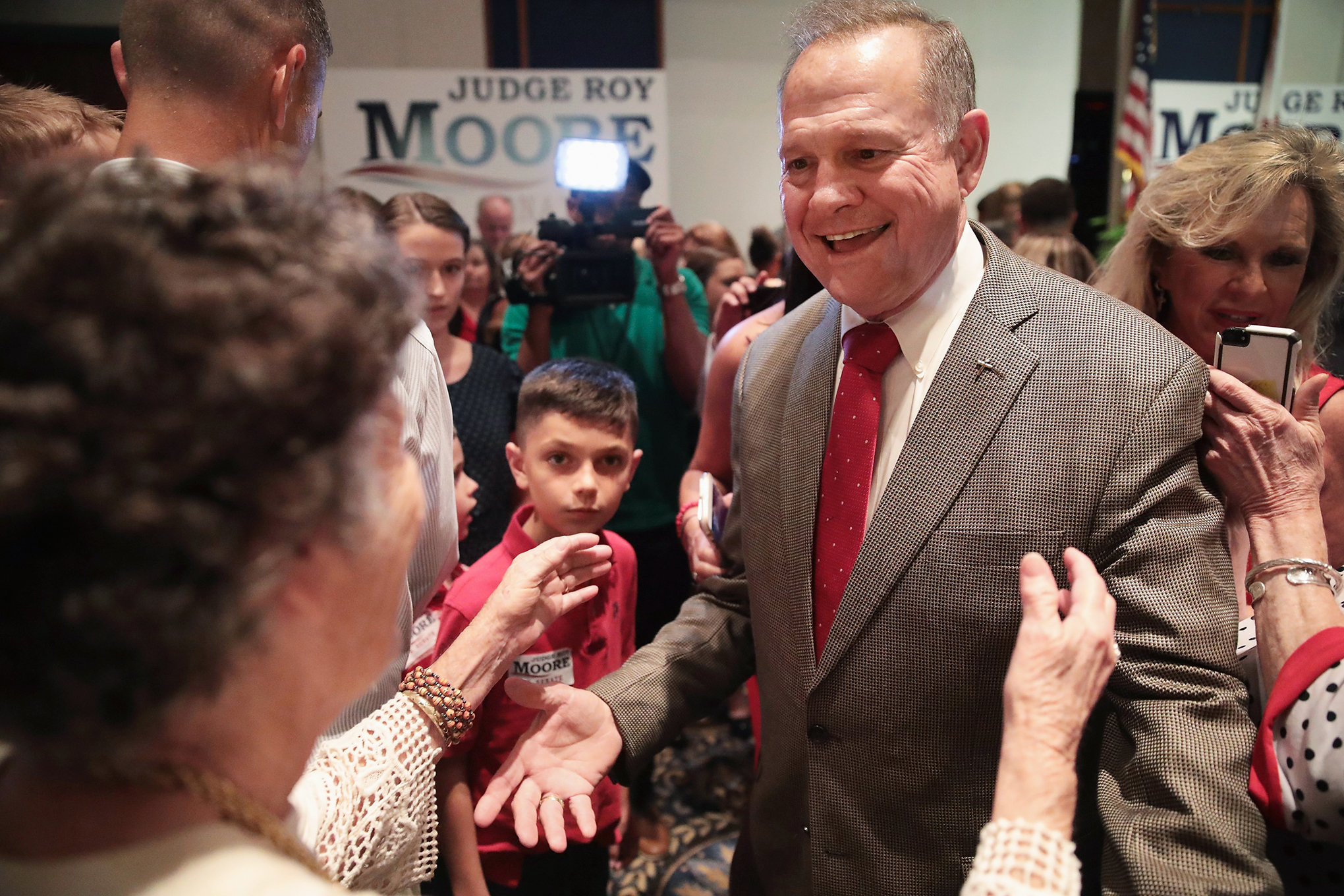

Roy Moore has been talking with God. It’s a brilliant October afternoon in downtown Montgomery, Ala., and inside the weathered brick home serving as the headquarters for Moore’s Senate campaign, the twice-removed former chief justice of the Alabama supreme court leans back in his chair and shares what the Lord has told him.

“Our rights come from God,” the 70-year-old Baptist says. “The Constitution was founded upon God. It was made for moral and religious people. It is the fallen nature of man that the Constitution meant to restrain.”

Moore is favored to win the Dec. 12 election to fill the Senate seat that was vacated when Jeff Sessions stepped down to become the nation’s Attorney General. And while several conservative rabble-rousers have joined the Senate in recent years–both Rand Paul of Kentucky and Ted Cruz of Texas come to mind–there is nobody in Washington quite like Moore: a judge who recites anti-abortion poetry, rejects the theory of evolution, doesn’t think Muslims should be allowed to serve in Congress, fought to keep antiquated wording in the Alabama constitution requiring school segregation and suggested the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks were God’s punishment for America’s sins. His first priority in the Senate, he says, will be to fight to impeach the five Supreme Court Justices who voted in 2015 to give same-sex couples the right to wed from coast to coast. (Such a move would make history: the last attempt to remove a Supreme Court Justice began in 1804, and proved a failure.)

Moore is not only a culture warrior. He is a populist Christian and a soldier in the larger Republican revolution that is rooted in frustration with Washington and prizes anti-establishment anger over all else. The same uprising that carried President Donald Trump into the White House looks poised to deliver an even more disruptive figure, one the party cannot control.

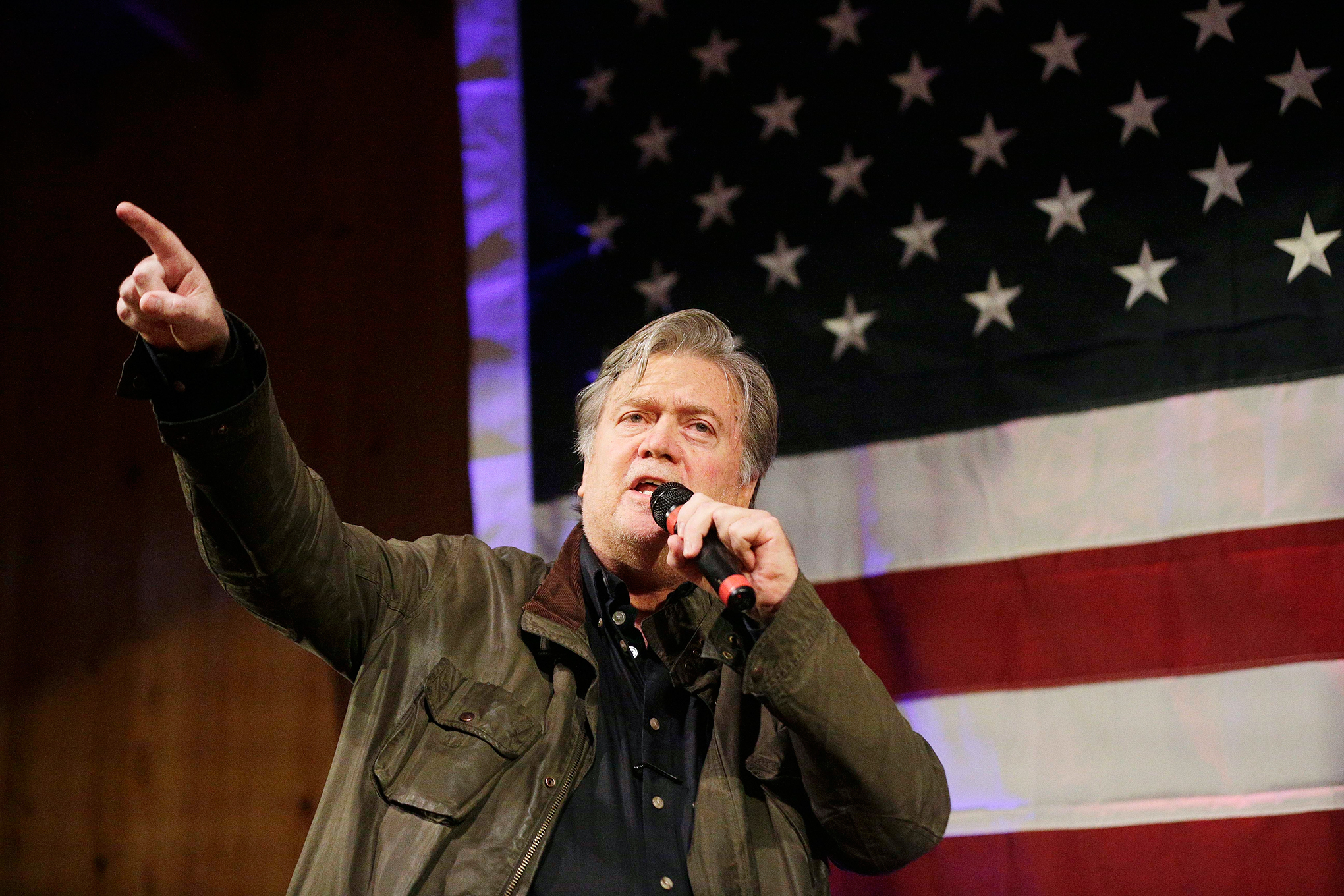

And the revolution is about to spread well beyond Dixie. Its field general, former Trump strategist Stephen Bannon, says he is recruiting a slate of insurgent outsiders who will vow to topple the Republican ruling class. “Right now it’s a season of war against the GOP establishment,” Bannon told a gathering in Washington on Oct. 14. Three days later, Bannon showed up in Arizona to endorse the right-wing Senate candidate Kelli Ward, who is running against incumbent Republican Jeff Flake, a Trump critic. Bannon’s allies say they plan to challenge sitting Republican Senators in Nevada, Mississippi, Montana, Wisconsin and West Virginia. “The anger we all saw bubble up in 2010 is even more pronounced now,” says Andy Surabian, a top Bannon lieutenant. “Every Republican who hasn’t lived up to their promises should be watching their backs.”

At a moment when the party should be capitalizing on unified control of Washington, the 2018 elections are shaping up instead as perhaps the nastiest GOP civil war in a generation. A collection of outside groups tied to Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell has already raised more than $40 million this fall to protect incumbents next year from Bannon’s insurgents, and donors are preparing to quadruple that if needed. At stake is whether the GOP remains a party of traditional conservative principles, or becomes something else entirely. Senator John McCain warned in an Oct. 16 speech his party risks following “some half-baked, spurious nationalism cooked up by people who would rather find scapegoats than solve problems.”

Gallant, Ala., pop. 742, is a quiet village in the foggy upstate hills, with a volunteer fire department, a post office and the town’s First Baptist Church. This is where Moore worships. “He’s a straight-shooter and a man of God,” deacon Arnold Gray says at an Oct. 15 prayer meeting. Faith has long been Moore’s foundation. The judge and his wife Kayla, who have been married for 32 years, live on a 50-acre property, protected by a locked gate, in a hillside house you can’t see from the wooded road. The Ten Commandments are posted above their bed. Moore, who doesn’t touch whiskey or beer, wears a 10-gallon hat and speaks extemporaneously–“I’m not a speechwriter,” he says–sometimes pausing to grin with his tongue between his teeth. He can recite whole passages of works that move him, from Blackstone’s Commentaries to the Federalist papers to his own poetry, which ranges from decrying “babies piled in dumpsters” to comparing love to butterflies.

Moore spent his formative years in Gallant, the oldest of five children born to a jackhammer operator and a homemaker. He was a studious child. “I never got any trouble out of that boy–he’s always loved going to church,” says his mother Evelyn Ridgeway. “He never went outside. I’d find him studying in his room at 3 in the morning. Kids used to make fun of him.” But Moore was willing to go his own way. He “prayed hard” to get into West Point, where he says his fellow cadets had little patience for “a Southern boy with a strong adherence to what I believed.” After a stint as a military police commander in Vietnam, he studied law at the University of Alabama and settled back in his home county. He made a reputation as a tough prosecutor. “I lost maybe four cases in five years, and I tried hundreds,” he says. After losing an election for a local judgeship, he spent a year working as a rancher in rural Australia. In 1992, he was appointed to preside over the 16th circuit court of Alabama after the sitting judge died.

Then came the move that put him on the map. “I’d prayed not to get appointed unless it was God’s will,” Moore recalls as he prepares to drive from his campaign headquarters to meet Kayla across town. “I got appointed. I had to start decorating my courtroom, and I figured I’d hang a big picture of Washington or Jefferson, but I couldn’t find any. So I pulled out a little plaque of the Ten Commandments that I’d made in 1980.” The American Civil Liberties Union sued, but Moore refused to budge. “I said ‘What, I can’t acknowledge God’s role in this?'”

In 2000, Moore was elected the chief justice of the Alabama supreme court. He soon commissioned a granite monument to the Ten Commandments–the “moral foundation of the Constitution,” he maintains–to sit in the rotunda of the courthouse. It weighed 5,280 lb. and drew nearly as many protesters. A legal controversy erupted, and in November 2003 the Alabama court of the judiciary removed Moore from office when he refused to ditch the monument. It made him a national celebrity among evangelicals. Moore took the reins of the Foundation for Moral Law, the judiciary-action group he founded in 2002 that fights for public prayer and against abortion and same-sex marriage. In 2012, he ran again for chief justice and won. Four years later, he was removed from the post by judicial officials once again–this time for telling Alabama judges not to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples, in defiance of the U.S. Supreme Court. “The ultimate goal of the movement is to drive the nation into a wasteland of sexual anarchy that consumes all moral values,” he wrote in an opinion on Obergefell v. Hodges, the Supreme Court case that he describes as a “sudden overthrow of our government.”

Says Moore: “I don’t hate people because they profess homosexuality. I hate sin. And sodomy has historically been an aberration of our laws.”

This isn’t the kind of talk you hear much anymore in Senate hallways. But then, Alabama is a deeply red state that has elected Senators like Sessions and, in the 1980s, Jeremiah Denton, who believed the U.S. was being destroyed by moral decay. When Sessions was nominated to become U.S. Attorney General, Alabama’s Republican governor, Robert Bentley, chose state attorney general Luther Strange to fill Sessions’ old seat until a special election could be held. At the time, Bentley was under state investigation on allegations that he had used taxpayer dollars to conceal an extramarital affair with a female staffer. Voters speculated that Bentley had sent Strange to the Senate so the governor would have a chance to pick a more favorable prosecutor. Bentley resigned. The suspicion hurt Strange. Says local conservative activist John Pudner: “Alabama doesn’t like insiders.”

Both Trump and McConnell backed Strange, but Bannon cast his lot with Moore, who was leading in the polls when Bannon touched down in September to endorse him in the closing days of the state’s GOP primary. “His team was up three touchdowns with 45 seconds left, and he found the first plane so he could be on the sidelines when the clock hit zero,” a veteran Republican strategist says of Bannon. Moore went on to beat Strange, capturing 54.6% of the vote. Moore downplays his ties to the Breitbart boss. “I met Steve Bannon when the primary was about toward the end of it,” the candidate recalls. “I talked to him on the phone and he offered his support. I said, ‘Well, fine, I’d love to have your support.'” Moore also professed surprise when Trump announced on Oct. 16 that he would be meeting with Moore the following week. “Well, that’s the first I’m hearing about it,” Moore chuckled several hours later. “But let’s make it happen.”

The Bible-quoting jurist and real estate mogul turned President may not have much in common. But their interests may align: a year after Trump’s election, mainstream Republicans still run things on Capitol Hill–and things still aren’t getting done. Multiple attempts to repeal and replace Obamacare have failed. The promised border wall is scarcely closer to reality. Tax reform is struggling to get off the ground, and a government shutdown looms on the horizon. “We have a slew of politicians that care more about their power than they do about doing what’s right for this country,” says Ed Henry, a Republican in Alabama’s house of representatives and a Moore backer. “That’s why Americans voted for Donald Trump, and that’s why Alabamians are voting for Roy Moore. They want to upset the apple cart.”

Bannon and his allies want to capitalize on this frustration. Their strategy is to knit together a disparate coalition, from evangelical populists to small-government libertarians, to take on the proverbial swamp. Already Bannon is jetting around the U.S., meeting with major Republican donors in a bid to convince them to defect from McConnell’s team. Along the way, he is advising would-be recruits on how to savage incumbents. Republicans are defending eight Senate seats in 2018, many of them in red states that are fertile ground for an upset. Only Cruz–a favorite of the wealthy Republican donors Robert and Rebekah Mercer, who have also bankrolled Bannon–appears safe from a primary threat. “The grassroots saw they can be successful with President Trump,” says Surabian, Bannon’s ally, “and they now see they can be successful in dislodging Mitch McConnell as majority leader and replacing squishy, weak-kneed Republicans with anti-establishment, America First–styled Republicans.”

One question Bannon has yet to answer is whether he can match McConnell’s cash. During the past two election cycles, establishment Republicans have trounced Tea Party–style insurgents in a sweep of competitive primaries. McConnell’s aides understand the stakes. The GOP leader tried to make sure the President understood them when they met privately on Oct. 16, after which the two Republican leaders took questions together in the White House Rose Garden in a forced show of unity. “You have to nominate people who can actually win, because winners make policy and losers go home,” McConnell told reporters, citing failed candidates like Christine O’Donnell, Sharron Angle, Todd Akin and Richard Mourdock, Tea Party–backed nominees who squandered winnable races.

Democrats insist that Moore could fall into the same category. His opponent in December will be Doug Jones, a 63-year-old former U.S. Attorney who made his name prosecuting the perpetrators of the 1963 Ku Klux Klan bombing of a Birmingham church that killed four African-American girls. That’s as strong a profile as a Democrat in Alabama is ever likely to get, but the odds are long. Trump won nearly two of every three votes in this state in 2016; no Democrat has been elected to the Senate from Alabama since Howell Heflin in 1990.

Republicans worry about Moore too; only a small fraction of the House Republican conference and even fewer of his Senate colleagues have endorsed his candidacy. Around Washington, GOP strategists have taken to joking about how Moore makes Senate hard-liners like Cruz, who sparked a government shutdown in 2013, look tame. Some fear that as the party pushes for a tax-cut package, Moore’s strong cultural views could present a distraction. In his interview with TIME, the judge remarked that NFL players who knelt during the national anthem in protest against police brutality or systemic racism were committing a crime. “It’s against the law, you know that?” Moore said. “It was an act of Congress that every man stand and put their hand over their heart. That’s the law.” (Moore was referring to a section of the U.S. code that outlines how people should conduct themselves when the anthem is played, but the code merely outlines proper etiquette; there are no legal penalties.)

If Moore loses in December, it would shave the party’s cushion in the upper chamber to a single vote–which means there is an outside chance that Moore’s rise and Bannon’s crusade could cost the party control of the Senate, giving Democrats the numbers, and the subpoena power, to thwart every aspect of Trump’s agenda. And in the much more likely event that Moore wins, the Senate is about to become harder to govern–if that’s possible. “Electing Moore would be like throwing a bomb into the Senate,” Jones says over coffee at a diner in the town of Moulton on Oct. 16. “He can’t work with anybody. People here don’t want to go backward, and some of his divisive and extreme rhetoric takes us back decades.”

None of this concerns Moore. Late on a Monday afternoon in October, he was sitting in the parlor turned conference room of the house that serves as his campaign office. The light was fading from the windows. Moore was about to drive over to the offices of the Foundation for Moral Law, which his wife Kayla now runs. The high-ceilinged offices in the historic Montgomery building still has five plaques of the Ten Commandments on its walls, and the judge keeps an office there where he plots his next battle. “You think the people of Alabama don’t understand what I believe?” he says. “It’s God’s providence that we’ve won, because it’s inexplicable in modern terms. There’s all this consternation in Washington over ‘What does this mean?’ It means the country is waking up to the relevance of God.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Philip Elliott / Washington at philip.elliott@time.com