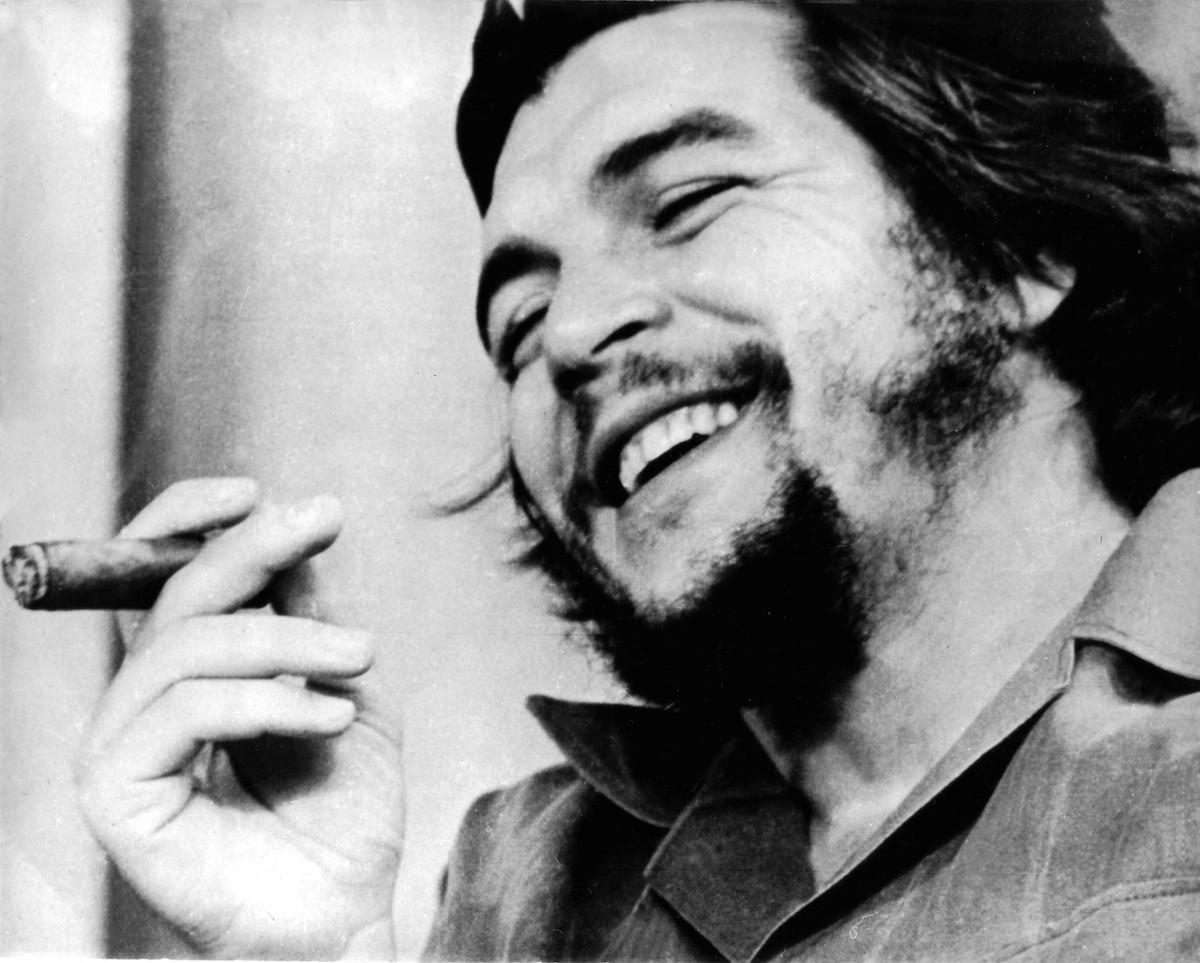

These days, as his face gazes out from t-shirts, murals and dorm-room posters around the world, it could be easy to think that Che Guevara — or, more commonly, simply Che — is more of an idea than a man. But he lived a human life which, as all lives must, came to an end 50 years ago, on Oct. 9, 1967.

Che had grown up in Argentina under the dictatorship of Juan Peron and had wanted to become a doctor before the ideals of communism and the revolution in Cuba drew his full attention in the 1950s. After he helped Fidel Castro come to power there, he served a number of roles within the Cuban leadership before the two men had what TIME would call a “bitter doctrinal dispute” in the mid-1960s. Che left the island, declaring that he had accomplished his duty to the Cuban revolution and that it was time for him to go to the assistance of that cause in “other lands of the world.”

But he soon found that revolutions he encouraged in South American nations would not come easy. Those who held power would fight hard to maintain it, and many peasants were not eager to turn to communist guerrilla movements as an alternative. And so, in mid-1967, he found himself hunted down in Bolivia, as TIME reported soon after:

The Quebrada del Yuro, deep in the stifling Bolivian jungle 75 miles north of Camiri, is a steep and narrow ravine that is covered with dense foliage. There, early last week, two companies of Bolivian Rangers totaling more than 180 men split into two columns and quietly stalked a handful of guerrillas. Shortly after noon, the troops spotted their men, and both sides opened up with their rifles and automatic weapons at a withering, point-blank range of 150 feet. After a lengthy fight, four Rangers and three guerrillas lay dead, and four other guerrillas had been captured.

One of the prisoners was no ordinary guerrilla. He was Ernesto (“Che“) Guevara, 39, the elusive Marxist firebrand, guerrilla expert and former second in command to Fidel Castro whose name had be come a legend after his disappearance from Cuba 2 1/2 years ago. Since that time, much of the world had thought Che dead (perhaps even at Castro’s hands) until his presence in Bolivia was dramatically confirmed a short time ago…

Dressed in a dusty fatigue shirt, faded green trousers and lightweight, high-top sandals, Che caught a bullet in his left thigh as he advanced toward the government troops; another bullet knocked his M-l semiautomatic carbine right out of his hands. In Che‘s rucksack, the Rangers found a book entitled Essays on Contemporary Capitalism, several codes, two war diaries, some messages of support from “Ariel”—apparently Castro—and a personal notebook. “It seems,” read one recent notebook entry in Che‘s tight, crisp handwriting, “that this is reaching the end.”

At Quebrada del Yuro, Che was loaded onto a stretcher and carried five miles to the town of Higueras. Informed of his capture, army leaders in La Paz, the capital, pondered what to do with him. Since Bolivia has no death penalty, Che, at worst, would go off to prison—perhaps only after a long, noisy trial, a propaganda outcry from the whole Communist bloc and the threat that other guerrillas might streak into Bolivia and make a cause of him. The next day, orders came down to Higueras to execute Che. He was shot two hours later.

Che’s body was taken to a hospital in the town of Vallegrande for examination and embalming. Though the army would claim that there had been no execution, doctors confirmed that he had died a day after his capture, not during the raid. He was laid in state for locals to observe that it was really him, and then he was cremated.

“His execution in Vallegrande at the age of 39 only enhanced Guevara’s mythical stature,” Ariel Dorfman noted decades later when he was included in TIME’s list of the most influential people of the 20th century. “That Christ-like figure laid out on a bed of death with his uncanny eyes almost about to open; those fearless last words (‘Shoot, coward, you’re only going to kill a man’) that somebody invented or reported; the anonymous burial and the hacked-off hands, as if his killers feared him more after he was dead than when he had been alive: all of it is scalded into the mind and memory of those defiant times.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com