When Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, begins on Wednesday night, it will mark the start of an annual period in which Jewish people around the world will take time to reflect on starting fresh in the new year.

But few celebrants in modern history have had more cause for such reflection than the Berlin Jews who survived World War II. In 1945, legendary LIFE Magazine photographer Robert Capa was there to document the first Rosh Hashanah service held in the city since 1938, which took place on Sep. 7, 1945, at Fraenkelufer, a synagogue that the U.S. Army had helped restore after the Nazis torched it. There, he found a people reconnecting with one another and trying to start practicing their religion openly again in a city that was also in ruins.

Capa would have understood their struggle. Born Endre Friedmann to a Jewish family in Hungary, he moved to Germany when he turned 18 in 1932 to pursue photojournalism. After Hitler rose to power, he fled to Paris and changed his name, having been inspired by the debonair director Frank Capra.

His background didn’t prevent him from covering the war against the Nazis. In 1945 alone, he had spent weeks photographing the ruins Berlin, parachuted with the 17th Paratrooper Division into the combat zone between the German city Wesel and the country’s border with the Netherlands, embedded with U.S. Army’s 2nd Infantry Division and produced a photo essay for LIFE on an American soldier killed by a German sniper to show the heavy days of fighting around V-E Day for the magazine’s “victory” issue.

But that Rosh Hashanah service was a time to document a city in peacetime, instead.

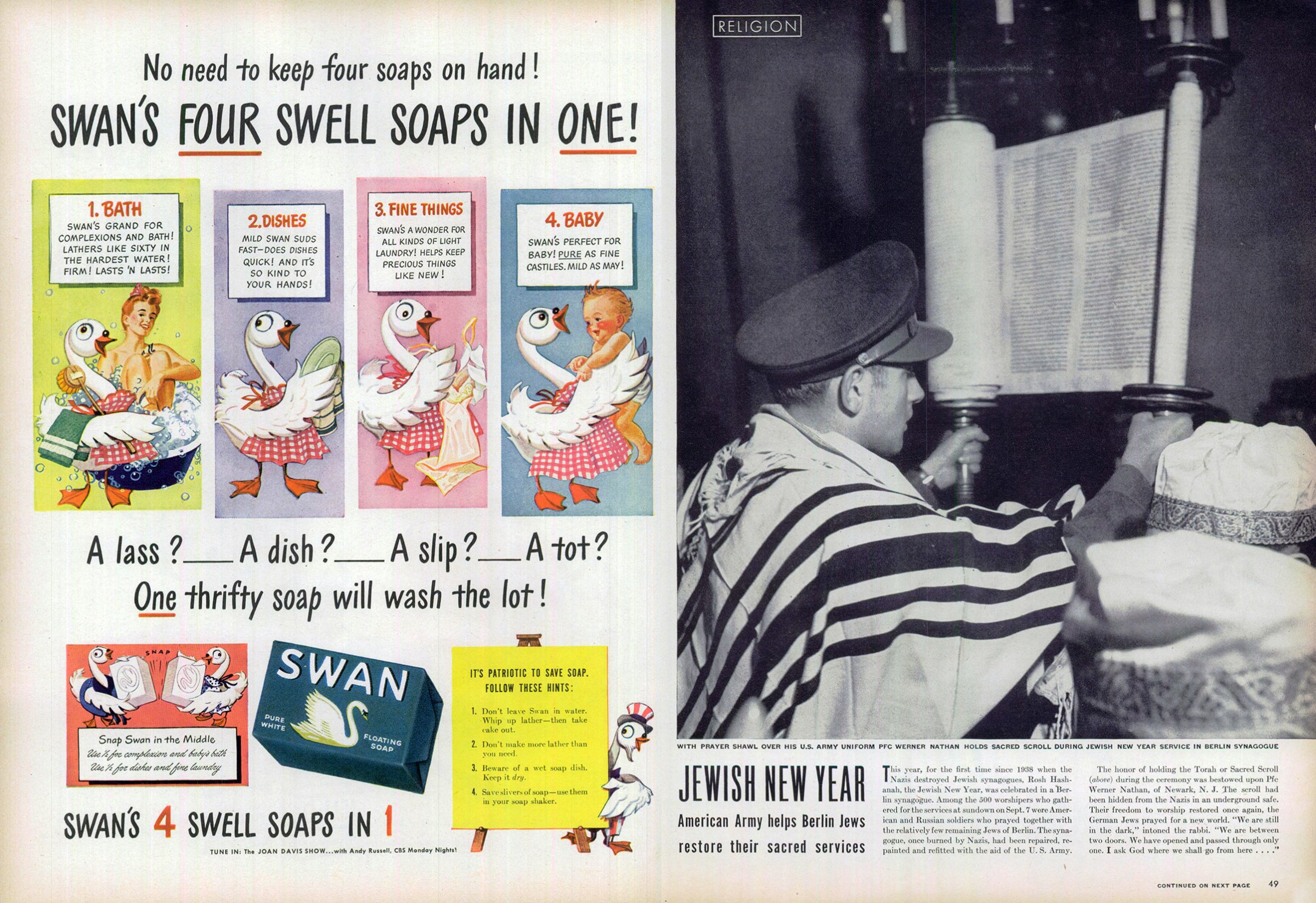

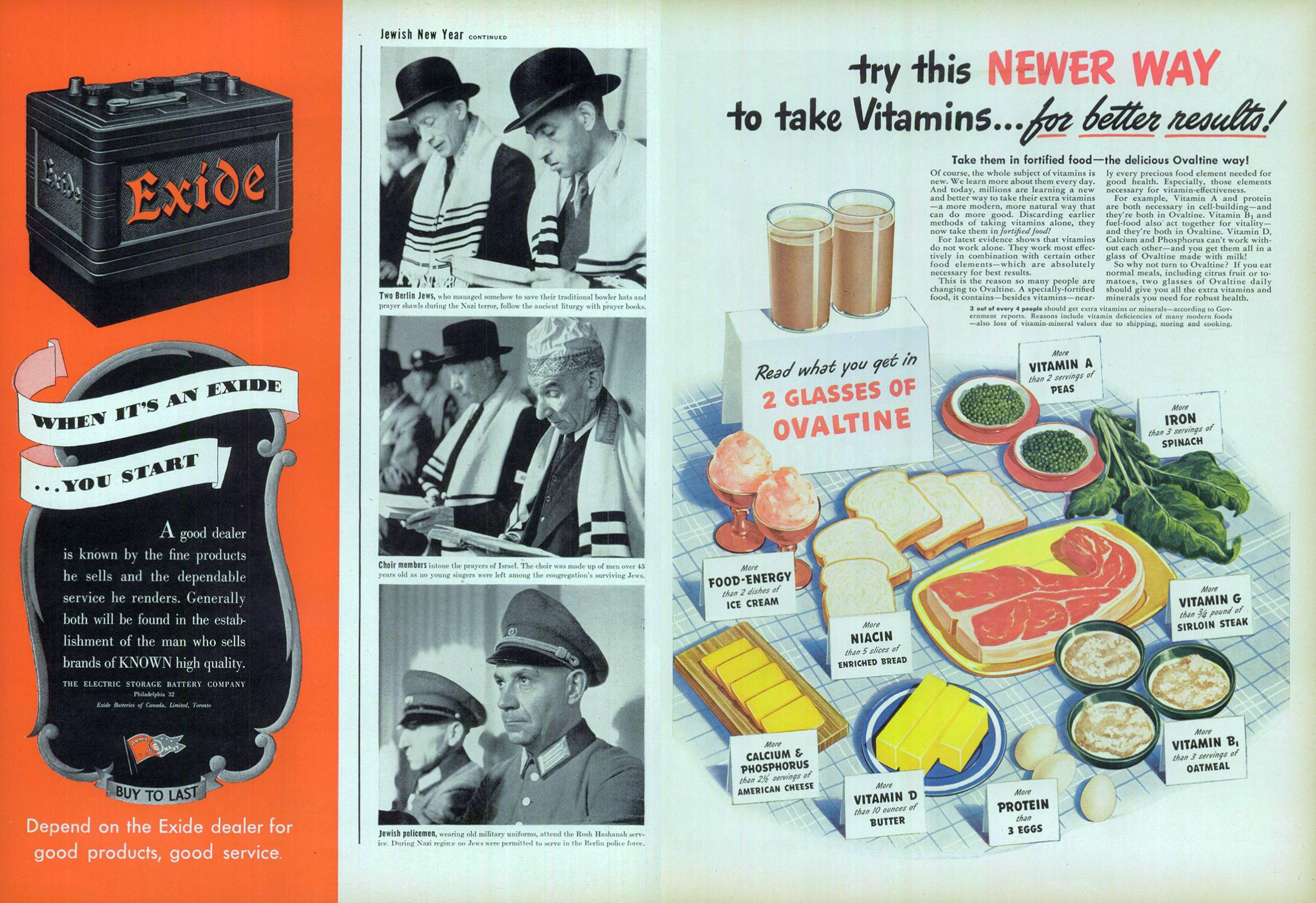

A photo essay in the Oct. 8, 1945, issue of LIFE reported that about 500 worshipers attended, including Jewish American and Russian soldiers. Donning a prayer shawl, Private First Class Werner Nathan of Newark, N.J., held the Torah, which the magazine explained “had been hidden from the Nazis in an underground safe.” The congregation’s rabbi had been killed during the Holocaust, so an assistant stood in, while “the choir was made up of men over 45 years old as no young singers were left among the congregation’s surviving Jews.”

Word about the service got back to the U.S. even before LIFE published Capa’s photos. The Sept. 8 edition of the Times-Picayune that year described a “mostly elderly” congregation that “sang the songs of Israel with tear-streaked faces,” according to a newspaper clip provided by current volunteers at the 101-year-old synagogue, which has been exhibiting Capa’s photos for the past year. Also in the newspaper clip, local rabbi Martin Riesenburger thanked one Jewish American soldier in particular — Harry Nowalsky, who worked across the street from Fraenkelufer, for being instrumental in planning the service. “You have brought us out of shame,” he is quoted as saying.

Nowalsky would have been one of the soldiers working with the American rabbis who were brought over to help restart religious Jewish life in the city, according to Dekel Peretz, one of the synagogue volunteers and a doctoral student of German and Jewish History who gives tours of Jewish Berlin and other city landmarks. But for those looking to start a new life, Peretz adds, there was another important reason to attend the Rosh Hashanah service: For those who thought about immigrating to America and wanted to know what life was like there, Berlin Jews could not only reconnect with one another, but also “connect with America.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com