The drive from Guam’s capital Hagatña to its hotel-studded tourist strip Tumon took 14 minutes 37 seconds in light traffic on a recent Monday. From Tumon’s military bars— Porky’s, Cowboy Ninja, Shamrock—due north along Marine Corps Drive, it takes another 14 minutes to reach the perimeter of Andersen Air Force Base, where B-1B bombers squat along the flight line. It also takes 14 minutes to barbecue a mackerel (seven for each side) for the local dish kelaguen, and about the same to make a transaction at the drive-thru of First Hawaiian Bank (at Bank of Guam, locals joke, it takes 40.)

Time, usually a slippery measure of island life, has taken on a chilling exactitude on Guam. The front-page headline of a recent edition of the Pacific Daily News read “14 Minutes.” That, the article explained, was how long it would take for four missiles launched from North Korea to travel the 2,100 miles to the western Pacific Ocean waters where the U.S. territory lies, and create what the hermit nation’s leader Kim Jong Un described as an “enveloping fire.”A few paragraphs down, a Guam Homeland Security official assured residents that should Kim pull the trigger, they would be “immediately notified by the 15 All-Hazards Alert Warning System sirens, located in low-lying areas throughout the island.”

Until recently, Guam, 210 sq. mi. of U.S. territory at the bottom of Micronesia’s Mariana Islands chain, would not have been familiar to many Americans. Few make the 6,000-mile trip across the Pacific to visit, and the island’s palm fringed beaches and flamingo sunsets lure mostly South Korean and Japanese tourists. But Pyongyang’s threats have made the U.S., and the world, pay attention to the island and its 163,000 American citizens.

North Korea’s threats came in defiance of a promise by U.S. President Donald Trump to respond with “fire and fury” to further provocations. On Aug. 15, Kim appeared to pull back, saying that he would watch U.S. actions “a little more” before ordering a strike on Guam. But the annual U.S. military exercises with South Korea, which Pyongyang vehemently opposes, are due to start Aug. 21 and could trigger yet more saber rattling—and, perhaps, hostilities.

The American military drives about 30% of Guam’s economy, and U.S. bases occupy a third of its land. Andersen Air Force Base lies to the north; Naval Base Guam and the Joint Region Marianas military command to the south. This was a primary launchpad for the Vietnam War and it’s from here, on Aug. 7, that seven B-1B bombers took off to fly sorties over the Korean Peninsula. It’s the Asian spear tip of the world’s biggest military, and consequently a target.

On the day of the “14 Minutes” headline, Guam’s government issued a two-page fact sheet titled In Case of Emergency: Preparing for an Imminent Missile Threat. Among the advice it gives island residents affected by fallout is to avoid using conditioner “because it will bind radioactive material to your hair.”

Ana Aguon, a local wearing a GOP Elephant t-shirt, says she has read the fact sheet but is worried that if bombs come at night there wouldn’t be time to heed its advice. “I told my kids just make sure you’ve got snacks so that whenever they tell us to evacuate you just grab your backpack and move,” she says.

Aguon’s middle-aged son Benny is selling guavas and soursop from a wooden crate near a colonial-era emplacement of Spanish cannons at Umatak Bay. “I’m just waiting for the rocket to hit and then kiss my ass goodbye,” he says. Then, grinning, he proffers the box: “That’s why I’m trying to sell all my fruit now.”

A few meters away, South Korean tourists take selfies at a monument to the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan, who reached Guam in 1521. About 150 years later, Spain colonized the island and its indigenous Chamorro people. Then came the Americans, then the Imperial Japanese during World War II, and finally the Americans again.

Barbara Dela Cruz, 82, still remembers the day the Japanese came. She was seven-years-old at the time and on an errand to deliver tuba — coconut wine — to an elderly man in another village. But, en route, the sirens sounded and scores of people came running in the opposite direction. Swept along with them, she made it home just as her family were preparing to flee. “We stayed under the bamboo groves for about a week, day and night, rain or shine,” she tells TIME over pancakes at a Hagatña coffee shop.

Dela Cruz, wearing a dark pink dress and pendants bearing Guam’s patron saint Santa Maria Kamalen, says “Japanese time” was tough, but because she was young she suffered less. She remembers studying the language for a year — she can count to ten and sing a song — before being pulled out of school to work. At one point, Imperial soldiers forced her and her new colleagues to watch the beheading of three Chamorros accused of spying. If she looked away or cried, they said, she’d be next.

On Liberation Day every July 21 Dela Cruz, along with tens of thousands of other Chamorro, celebrates the return of the Americans. Wistfully, she sings a calypso-like wartime ditty that reflects the warmth many then felt: “Sam, my dear Uncle Sam, would you please come back to Guam,” it goes. “I don’t like sake, I like Canadian [whiskey]/I don’t like the Japanese, I love American.”

‘Where America’s Day Begins’

Not everyone feels that warmth today. Lisalinda Natividad, an assistant professor at the University of Guam, says that Liberation Day, which marks the U.S. defeat of the Japanese every July 21, is “really more about reoccupation.”

Located just west of the international dateline, Guam’s tourist slogan is “Where America’s Day begins.” Its biggest store, by some measure, is a Kmart, and it consumes more spam per capita than anywhere else in the world. But despite such credentials, the island’s only representative in Washington is a non-voting delegate in Congress. The contrast between Guamanian love of the U.S. and America’s disregard of it was sadly highlighted when — shortly after Kim’s recent threats — Fox News said that just “3,831 Americans” stood to be affected by an attack there. But of course all the Chamorro are American.

Although Guam’s military enlistment rate is higher than that of any U.S. state, Natividad says, that is a reflection of the lack of other opportunities on an island where more than a third of the population qualifies for food stamps. At the Pay-Less supermarket downtown, half a gallon of milk costs about $7 — twice what it costs on base.

Older Chamorros like Dela Cruz balk at the idea the U.S. is anything but a loving, paternal benefactor. “Why should we hate the military? That is our protection,” she says. Then lamenting the rocky land in her village: “We have nothing here. If the Americans don’t supply us any food, what are we going to eat?”

For University of Guam President Robert Underwood there’s a clear generational divide in how Guamanians regard America. “Older people when they feel an external threat like that, they want to hold onto the U.S. more tightly because it’s the U.S. that will protect us; it’s the U.S. that will give us the missile batteries,” he says. “Then younger people are saying, it’s the U.S. that’s causing us to be a target.”

The Pacific has certainly paid a heavy price for the U.S. military presence. Between 1946 and 1958, Washington tested a staggering 67 nuclear weapons in the Marshall Islands — which are about 1,400 miles east of Guam — including the 15-megaton Castle Bravo thermonuclear hydrogen bomb that devastated Bikini Atoll. In his book What We Bury at Night, Guamanian human-rights attorney Julian Aguon chronicled how irradiated Marshallese mothers gave birth to “jellyfish babies” with translucent skin and no bones. Now its the Chamorro who are threatened.

“[Guam is] a photograph of the gulf between the ones who make the decisions and the ones who suffer the consequences of those decisions,” Aguon says. “When you live in a colony, you’re easy meat.”

Guam has endured a brutal Japanese occupation, a 1962 typhoon that destroyed 95% of the island’s then mostly wooden houses, a 7.8 magnitude earthquake in 1993, and the military occupation of its lands and seas. It’s no stranger to existential threats either: in 2013 China unveiled its DF-26 intermediate range ballistic missile (IRBM) – dubbed the “Guam killer.” That same year, the U.S. temporarily deployed its THAAD missile defense system here in response to Pyongyang’s threats. But this time feels different and more volatile the locals say. “There’s no more boondocks to hide in,” Dela Cruz points out. “One shot, Guam is gone.”

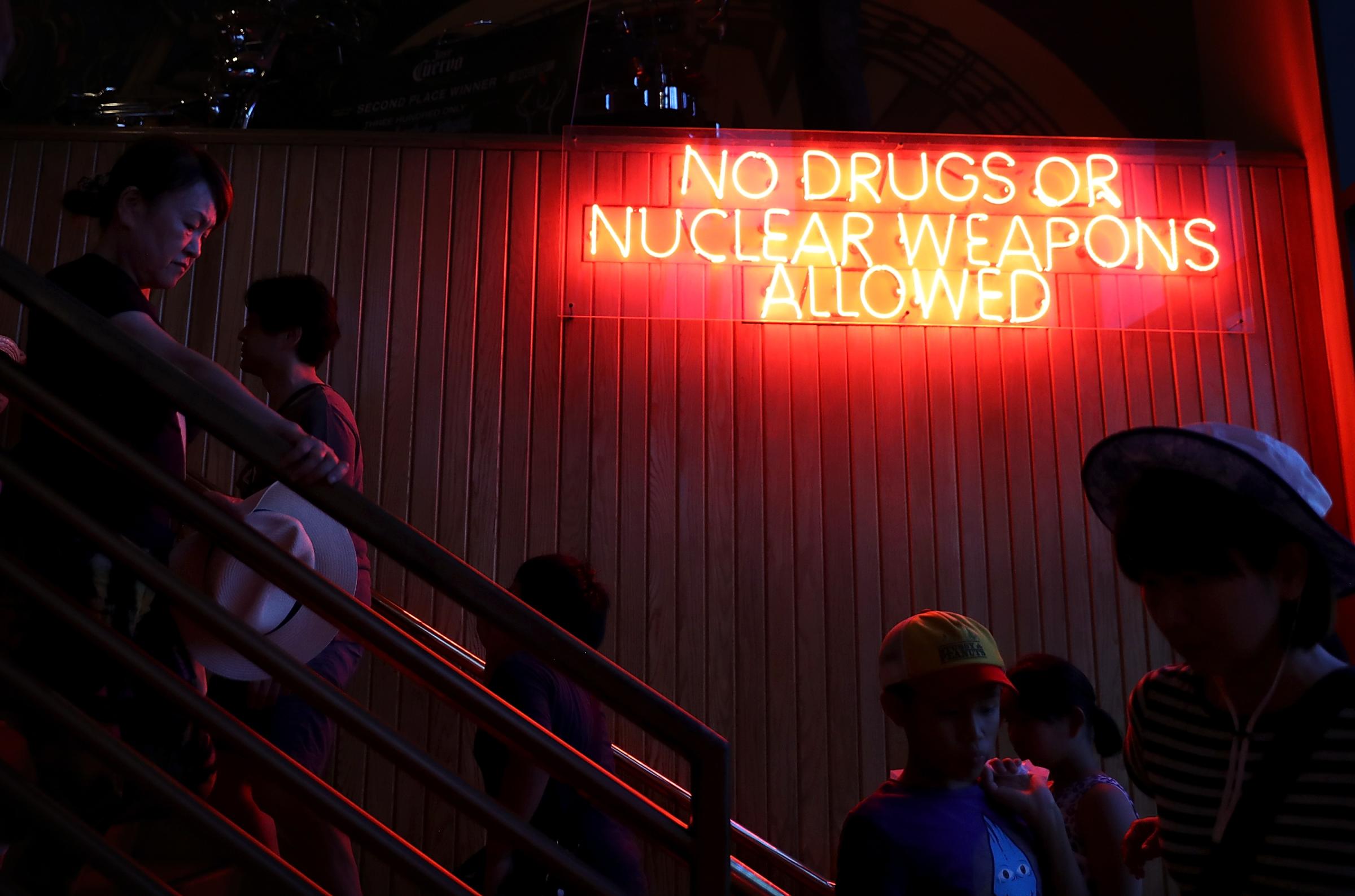

Still, last Saturday, the flow of life went unimpeded. Scores gathered at Ipao Beach Park to protest plans for a new firing range that they said would discharge 7 million rounds of ammunition a year in sacred ancestral lands. Guamanian ecologists fretted about the impact of the invasive brown tree snake on the island’s bird population and the invasive coconut rhinoceros beetle on its palms. At Capras beach, Chamorro teens fired up a barbecue, waded a jet ski out toward the reef, and passed a bong around. At Tarague Beach on Andersen — a sublimely beautiful sweep of white sand requisitioned for the sole use of the U.S. military — off-duty servicemen and women splashed in the turquoise shallows; later, at Porky’s, they shot Triple Sec B52s and sang along to 1980s hits.

That day too — four after Kim’s initial threat — Trump placed a call to Guam Governor Eddie Calvo. He assured Calvo that he was “1,000%” behind him and suggested he enjoy the attention, adding that tourism is “going to go up, like, tenfold with the expenditure of no money.” Some, however, caught an unusual note in the U.S. President’s diction. He called Calvo, Trump said several times, “to pay [his] respects.” Between two men just shooting the breeze, it was an oddly funereal phrase.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Joseph Hincks / Hagatña, Guam at joseph.hincks@time.com