Alexander Hamilton boasts many claims to fame: He was Secretary of the Treasury and the brains behind a national bank, founder of The New York Post, co-author of the Federalist Papers and the inspiration for a Tony Award-winning musical.

But this week, the U.S. Coast Guard community celebrates his role as the “father of the U.S. Coast Guard,” the oldest continuous seagoing service. Friday marks the anniversary of the date in 1790 when Congress approved his plan for a small fleet to ensure the safe conduct of trade.

About a year into Hamilton’s tenure as the nation’s first Secretary of the Treasury, the U.S. had hit rough seas, financially speaking. The American Revolution had created millions in debt, especially to France. There was no income tax to raise money, so the nation had to rely on tariffs on luxuries brought into the country.

However, in the lead-up to independence, the colonists had gotten pretty good at avoiding paying those fees. The high seas were the first highways, and a boat with a cargo of rum could be cruising up to Boston, when, to avoid paying a duty on the liquor, its crew might hand off the good to a small boat that paddled out to meet it.

“It was considered patriotic to smuggle because you were preventing funds from getting back to the British,” says Jennifer A. Gaudio, curator at the U.S. Coast Guard Museum at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy in New London, Conn.

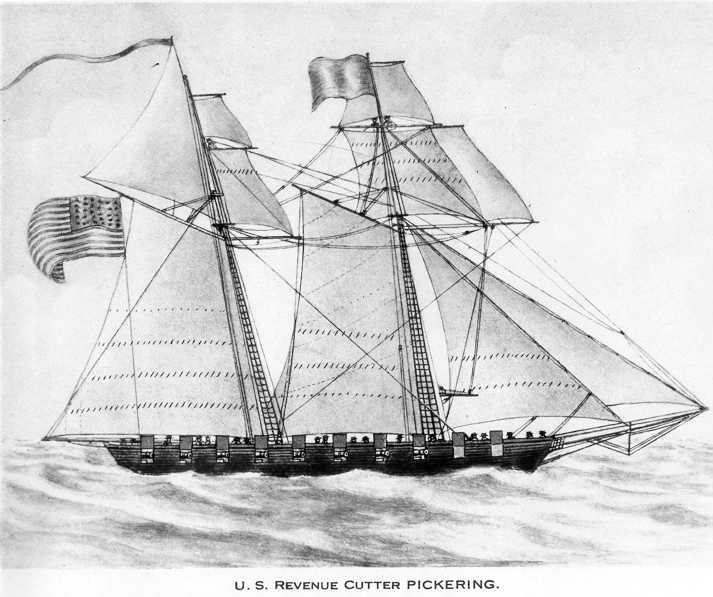

As part of his plan to reduce the nation’s debt, Hamilton federalized the nation’s lighthouses and called for ten ships known as “revenue cutters” to check out the cargo on ships heading to U.S. ports and make sure the goods they declared matched up with the items actually on board. The government hired ex-smugglers, who could spot the small boats used for the practice, and established a military-inspired system of ranks. Customs agents at the ports would report to the federal government how much money they collected periodically (though they could be bribed easily).

The boats’ first major test came during the so-called “quasi-war” with France at the very end of the 18th century.

“The French got annoyed that we weren’t paying [debts] back as fast as they wanted, and annoyed that we were trading with the British, which it was at war with,” Gaudio explains, “so French privateers were sent over to capture American merchant ships and keep them to recoup their losses. The only agency around to fight them was the revenue cutters service.”

The U.S. did not end up going to war with France, but the expanded role of the seafaring service stuck.

Nowadays, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection handles taxes and duties, but the requirements for the job that Hamilton spelled out in a letter for the service’s first officers — to be “prudent, moderate and good tempered” — have become a timeless mantra of sorts for current service members.

“Officers will always keep in mind that their fellow citizens are free, and, as such are impatient of anything that bears the least mark of a domineering spirit,” reads a version edited for modern-day readers. “They should carefully refrain from anything resembling arrogance, rudeness or insult. They will strive to overcome difficulties by a cool and even-tempered perseverance in their duty.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com