Riley Anderson was a C student in high school, bored by the work and driven partly by a desire to stay on the football team. In 2015, he graduated 25th in his class–of 31 students.

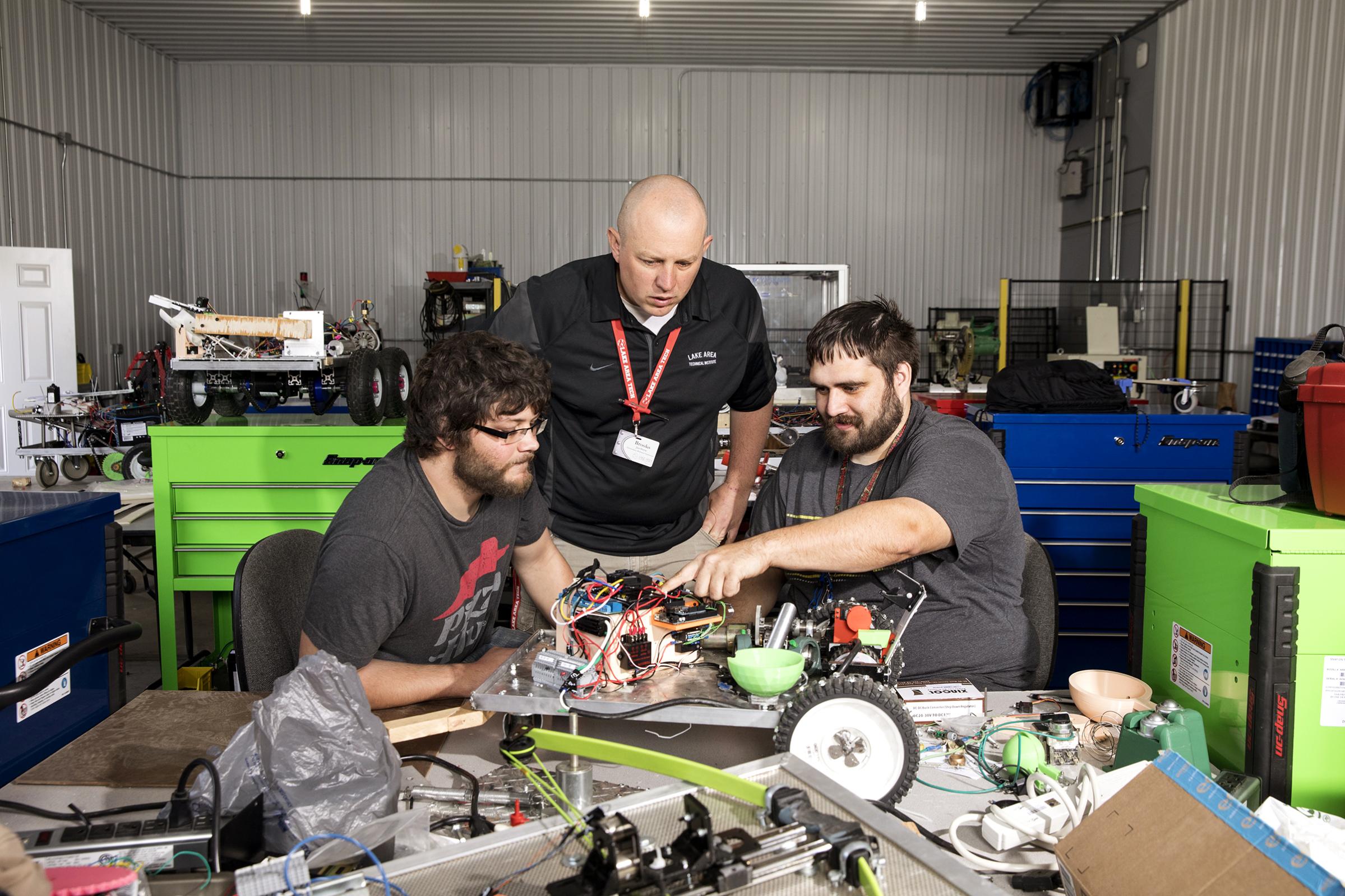

Without a particular career in mind, Anderson enrolled at Lake Area Technical Institute (LATI) in Watertown, S.D., a relatively inexpensive two-year college 30 minutes from his home. There, his classrooms were hangar-size spaces filled with wind turbines, solar panels, ethanol distillers and miniature hydroelectric dams. It seemed more like his dad’s garage, where Anderson would spend hours tinkering with his 1971 Chevrolet pickup truck, than a place to learn math. But trigonometry began making sense when you used it to fit together piping systems. Basic computer code seemed worth learning when you could program an assembly-line robot.

The former C student soon started making straight A’s. He graduated in May with a 4.0 GPA and, most important, a job lined up. Two years after squeaking by in high school, Anderson is set to become a maintenance technician at 3M. His annual starting salary is $60,000. The South Dakota median is a little over $53,000.

LATI is a model for the growing number of politicians, CEOs and academics who believe that community colleges have the potential to become much needed engines of economic and social mobility. Last year, 99% of its students entered the workforce or went on to four-year colleges. The school has an 83% retention rate, well above the national community-college average of about 50%, and few instances of students’ defaulting on their loans. The evolving curriculum is designed with input from more than 300 regional businesses, and starting salaries for LATI alumni average 27% more than those of other new hires in the region. All of this has led the college, with a student body of almost 2,500, to 14 consecutive years of growing enrollment. Officials originally projected that LATI would reach its current size in 2040.

That success, sadly, is an outlier. Across the nation, community colleges–which educate about 40% of all undergraduates in the U.S.–are facing declining enrollment and tightened budgets. Even as officials hold them up as the answer to bridging America’s yawning blue-collar-skills gap, many are ill equipped to deliver on the promise. Less than 40% of community-college students graduate, and many drop out their first year. While more than 80% of two-year students say they want a bachelor’s degree, only 14% get one after six years.

The schools, meanwhile, are increasingly reliant on money from students as states cut funding, an added burden on a population that can ill afford it. Low-income students outnumber middle- and high-income students at community colleges by 2 to 1, and a recent study estimated that as many as 14% may be homeless.

The schools “are facing huge problems,” says Sara Goldrick-Rab, a professor of higher-education policy at Temple University, who supports making community college free. “I don’t think they’ve ever been more vulnerable.”

At the same time, the value of an associate’s degree has never been clearer. Currently, the median salary for someone with only a high school diploma is $36,000. For those with a community-college degree, it’s $42,600. And that gap is projected to grow as automation transforms the U.S. workforce, making higher-level science, technology, engineering and math skills critical in fields that once required little more than manual dexterity. Earlier this year, 48% of small businesses reported that they couldn’t find qualified job applicants to fill open positions, according to the National Federation of Independent Business.

Recognizing the need, states across the country have taken steps to make community college more accessible. In May, Tennessee expanded its popular free community-college program, from accepting only high school graduates to all adults in the state. The month before, New York become the first state to offer free tuition for both two-year and four-year public institutions, albeit with cost exemptions and conditions that have been criticized by free-college advocates. Oregon made community college free for in-state students in 2015, while Arkansas and Kentucky are developing similar programs.

The importance of two-year schools was routinely emphasized by President Obama, who called for making community college free in 2015. But the proposal faced opposition from the Republican-led Congress and went nowhere. Despite winning a majority of rural votes in 2016, President Trump has barely discussed two-year schools, while proposing a 13% cut for the Department of Education, a plan that could make it even more difficult for the nation’s most vulnerable schools to serve their students.

America’s first community college is widely thought to be Joliet Junior College in Illinois, which was founded in 1901 to prepare students for a so-called senior college. Dozens of others followed, but their mission evolved after the Great Depression. Instead of providing a foundation in the liberal arts, many two-year schools became job-training centers, churning out teachers, nurses, police officers, pilots and even dentists. Compared with four-year colleges, they attracted more women, minorities and lower-income students and tended to be concentrated in small cities and rural towns.

Today community colleges largely break down into two categories: schools meant to help students transfer to a four-year college, and occupational institutions like LATI that are focused on placing students in jobs. Both grant associate’s degrees, cater to commuters and other nontraditional students and offer a comparative bargain: average annual community-college tuition is roughly $3,520, compared with $9,650 for four-year public colleges and $33,480 for four-year private colleges.

Since the Great Recession, the vocational approach has become the favored model. “Community colleges are now seen as the primary vehicles for workforce training in this country,” says Carrie Kisker, director of the Center for the Study of Community Colleges. According to a 2016 report from Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce, 11.6 million jobs were created in the recovery. All but 100,000 of those jobs went to people with some college education.

But the national emphasis hasn’t translated into widespread results. To many education-policy experts, the poor graduation and job-placement rates at most community colleges are the result of asking underresourced schools to serve underresourced students. Students often work part or full time to afford tuition, and many are parents. Too many schools, meanwhile, lack robust counseling departments or career-services offices to keep students on track, let alone affordable on-campus child care.

“A very big reason for the lack of success is that students have no idea what they want to do–they just know they want to go to college,” says Sandy Baum, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute. “And there aren’t enough resources to provide appropriate guidance.”

The problems are particularly acute in places that stand to benefit most. In Pennsylvania, which has a need for skilled workers after losing tens of thousands of blue collar manufacturing jobs, community-college graduation rates are some of the lowest in the country. Bucks County Community College in Newtown, Pa., graduated 12.3% of its students in 2014, according to the U.S. Department of Education. At Community College of Philadelphia, the figure was just 9.8%.

The culprits are many. Pennsylvania’s 14 community colleges are run as stand-alone shops, without a state-level office to coordinate them. Unlike South Dakota’s LATI, which shapes its coursework around the needs of employers and relies on their donations of heavy-duty machinery for its classrooms, Keystone State schools have been left largely on their own. “The chronic lack of resources makes it more difficult for community colleges to respond to the workforce needs than in a state where they’re better supported,” says Kate Shaw, executive director of the Philadelphia-based education nonprofit Research for Action.

Other schools have found success with more creative approaches. In Texas, Austin Community College recently redesigned an old shopping mall to become a high-tech learning lab with more than 600 computer stations. Northern Virginia Community College, one of the nation’s largest two-year colleges, with roughly 75,000 students (the largest is Indiana’s Ivy Tech Community College system, with 170,000), now develops curriculums with George Mason University to make it easier for its students to transfer for a bachelor’s degree. Pierce College in Washington State has dramatically increased its graduation rates by mandating a college-success course, doubling its tutoring services and allowing faculty members to see how many students complete each course.

The City University of New York doubled graduation rates in its two-year program after offering free tuition, books and even public transportation for students who register full time. Other schools in New York and California have announced similar programs.

Few states have taken bigger strides than Tennessee, which not only made community college free for high school graduates beginning in 2015 but also overhauled how its schools organized their curriculums. The schools now offer a structured group of eight disciplines rather than dozens of programs. After two years, more than 33,000 students have taken advantage of the Tennessee Promise, increasing first-year community-college enrollment by 30%.

“It has completely changed the conversation at the dinner table,” says Tristan Denley, vice chancellor for academic affairs at the Tennessee board of regents, which runs the state’s community-college system. “Five years ago, students might ask Mom and Dad, ‘Can I go to college?’ Now it’s ‘Where should I go to college?'”

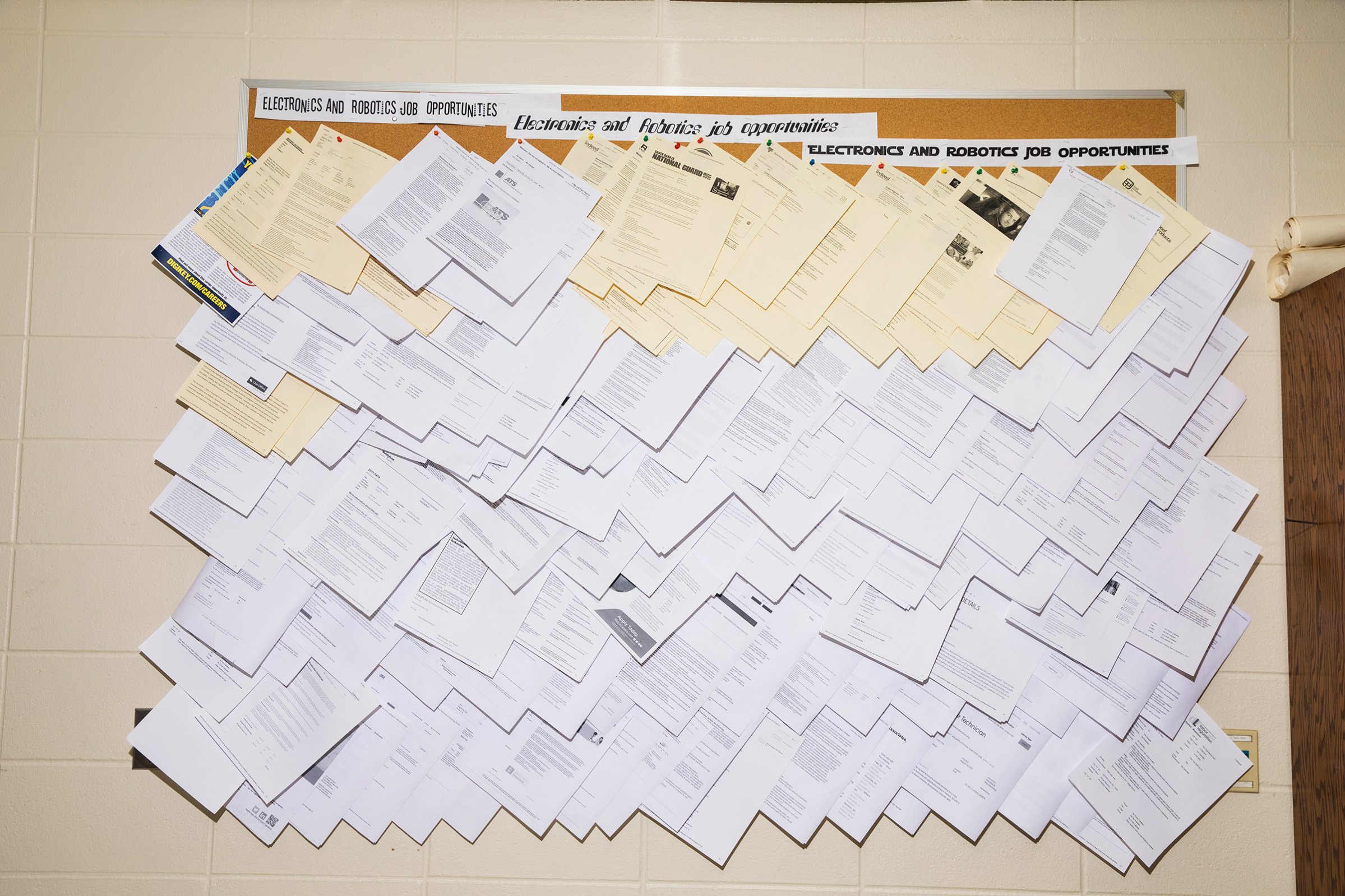

LATI’s 40-acre campus is filled with semitrucks, miniaturized assembly lines, industrial robots, 3-D printers, LED panels and even a tiny city that will be powered by a wind turbine on the school’s roof. But its best advertisement is decidedly low tech: a bulletin board inside the electronics and robotics department covered in overlapping printouts, each one touting a job opening. “To us, a student is successful if they’re placed,” says Mike Cartney, LATI’s president. “We talk to them about ‘Where do you want to be? Where do you want to go with your life?'”

For most students at LATI, the answer is securing a well-paying job with one of the hundreds of companies that help keep the school responsive. In fact, demand has pushed wages so high that legislators in this deeply red state recently increased the sales tax to help pay community-college instructors more than the starting salaries of their students.

“Lake Area gives you the nudge,” said Riley Anderson in the weeks before he finished school and prepared to start one of those well-paying jobs. “Most of my class already has jobs lined up, and it’s a month before graduation.”

Correction: The original version of this story incorrectly described the organization for Pennsylvania’s community colleges. The state does have an umbrella group—the Pennsylvania Commission for Community Colleges—that advocates for the state’s two-year schools.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com