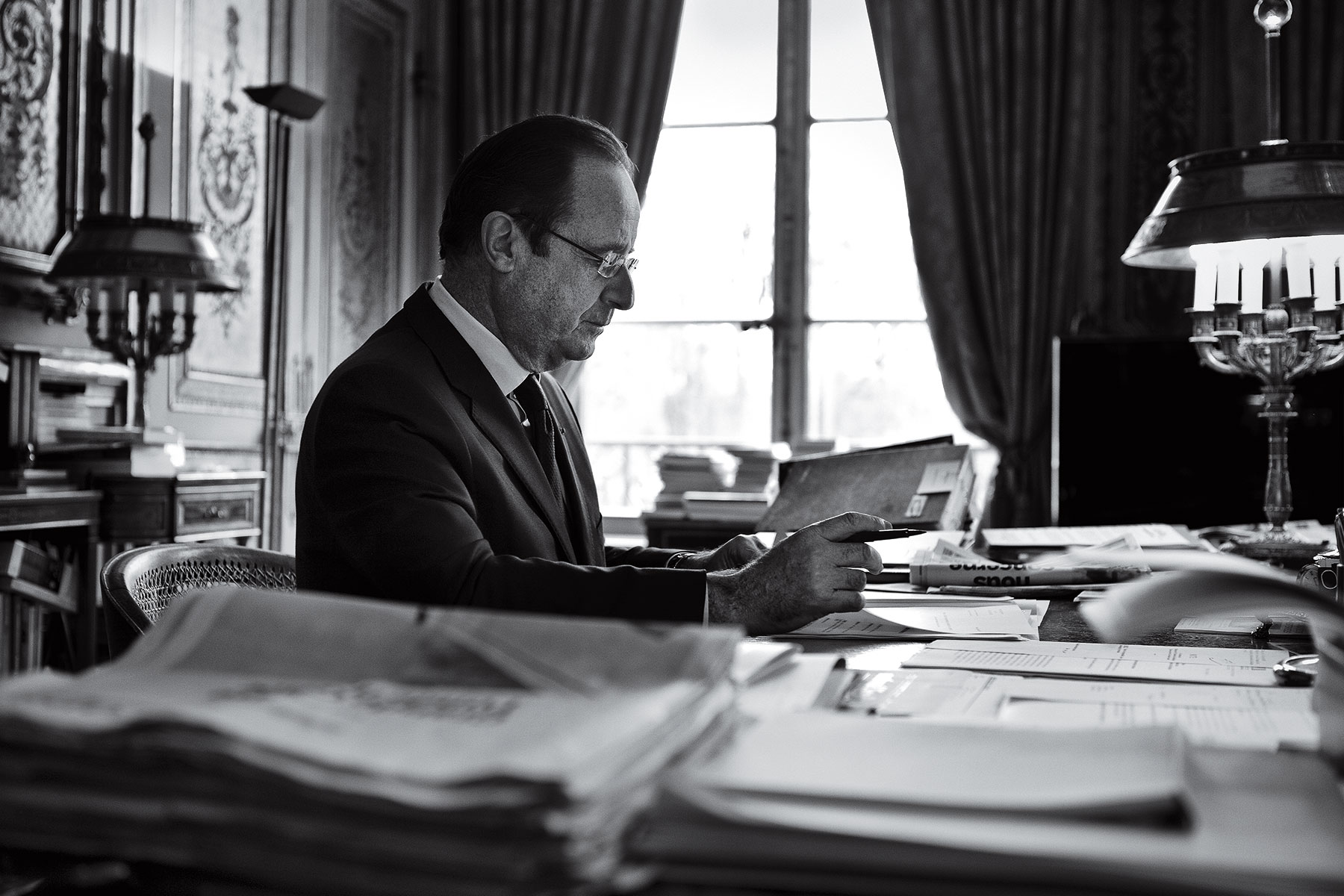

French Presidents don’t so much govern as reign from the splendors of the Élysée Palace. They have powers most democratic leaders only dream of, able to deploy their military or command nuclear strikes without first consulting the national legislature. Yet François Hollande, like his predecessors, faces a defining question: Can he, will he, fix France?

That’s because the French love revolution but hate reform, and the power invested in their heads of state is still ranged against the noisier forces of the street. Even as Hollande works the levers of the Élysée, Paris once again fills with protesters. A “Day of Anger” on Jan. 26, loud and inchoate, brought together thousands of people with different gripes who denounced everything from Hollande’s economic plans, with which some disagree, to his private life, of which some approve. On Feb. 2, tens of thousands converged again, protesting his pledge to enable fertility treatment for gay couples, which forced him to delay the legislation.

Hollande’s romantic woes have generated worldwide headlines, but it’s his economic plans that have implications well beyond his borders as he prepares for a state visit to the U.S. on Feb. 11. The performance of the world’s fifth largest economy, home to 31 of the world’s biggest corporations–including energy giant Total and cosmetics company L’Oréal–affects not only the well-being of its own citizens but the fragile global recovery. Foreign investment in France plunged 77% last year, while unemployment hit 3.3 million in December. The public sector has been allowed to grow unfettered for decades, representing some 57% of GDP. The government is France’s largest employer.

There was, therefore, relief in capitals from Washington to Berlin on Jan. 14 when Hollande, flanked by his ministers in the Élysée’s cavernous function room, the Salle des Fêtes, set out plans to cut the bloated state and make France more business-friendly. This marked a sharp change of direction for a President elected on a Socialist Party ticket. In a Jan. 25 interview, he told Time that he has no accompanying desire to trim French ambitions down to size. As commander in chief of the largest military in Europe, he has sent troops to address savage conflicts in West and Central Africa, supported U.S. efforts in Syria and helped wrest concessions from Iran.

The President is a key global player, but he’s uncomfortably aware that attention is focused on another part of his life. Since Jan. 10, the celebrity magazine Closer has tossed aside the French convention of respecting the personal privacy of public figures by publishing details of the 59-year-old President’s alleged affair with 41-year-old actress Julie Gayet. Perched gingerly on a damask sofa in the presidential palace, Hollande flushes visibly when asked about his predicament. “Private life is always, at certain times, a challenge,” Hollande says, and his is just beginning: hours after speaking to TIME he issued a terse statement confirming a split with the First Lady, journalist Valérie Trierweiler. In interviews on Jan. 30, Trierweiler indicated that she may write a memoir covering her time in the Élysée, which she described as “a world where betrayal pays.”

As Hollande is learning, the palace walls have grown increasingly transparent. That’s good news for anyone fascinated by his relationship tangles–and that would appear to be a surprisingly big audience. But it’s a sobering thought for anyone with an interest in the French recovery–and that’s a far broader swath of the planet. In becoming President, Hollande became the embodiment of France. His success or failure is bound up in the success or continued decline of his country. Amid gossip and sniggers, with the lowest poll ratings of any French leader in 50 years, the mild-mannered politician looks like an unlikely economic miracle worker. That might just count in his favor.

Hollande Exposed

In a 2012 campaign video for Hollande, Gayet lauded “the force of his oratory.” But most fans admit that the President is more impressive in person than on a podium. A onetime economic aide to the Fifth Republic’s first Socialist President, François Mitterrand, Hollande was nicknamed Flanby after a brand of custard pudding for his low-key, soft-edged style. In 2006, he sought the Socialist Party’s presidential nomination, only to be overtaken by his long-term partner and the mother of his four children, Ségolène Royal. (After Royal lost the following year’s presidential election to Nicolas Sarkozy, it transpired that she had already lost Hollande to Trierweiler.) When the Socialists began preparing for the next presidential contest, hopes rested not with Hollande but with the managing director of the International Monetary Fund, Dominique Strauss-Kahn. His 2011 arrest in Manhattan, on allegations–which he denies–of sexually assaulting a hotel maid, catapulted Hollande back into the frame.

A tide of discontent carried him over the finish line. Sarkozy, or “Sarko,” suited the boom times. He was flashy and pugnacious, with a watch reputed to have cost $74,500, a gift from his supermodel turned musician First Lady, Carla Bruni. But in the bleak spring of 2012, his “bling bling” angered voters, persuading just enough of them to gamble on Hollande, who positioned himself as “Monsieur Normal” and promised to champion ordinary people. During his nearly two years in office, he sought to do so by favoring economic stimulus over budget discipline and targeting tax increases on the very rich, some of whom, like movie star Gérard Depardieu, chose to leave the country.

The past weeks have exposed a Hollande whom only his closest intimates had previously glimpsed. Not on account of his love life: by the standards of most ex-Presidents, including Mitterrand, who maintained two families and numerous liaisons, Hollande appears to be a paragon of restraint, on a par with Sarko, who merely divorced and remarried in office. But the January relaunch of Hollande’s presidency saw him discard more than a few ideological veils.

He has pledged to slash public spending by $68 billion between 2015 and 2017. He has also proposed a “responsibility pact” with businesses to cut taxes and red tape in exchange for a commitment to create jobs and boost training.

These are pledges the business community has longed to hear. “It’s a very major move,” says Pierre Gattaz, president of MEDEF, France’s employers’ union. “We can create 1 million jobs if we can solve some [of these] problems.” To Hollande’s core constituency of middle- and lower-income voters, his new direction could seem like a betrayal. Leftist leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon labeled the plans “a gift to companies.” The President rejects notions that he has departed from his Socialist roots. Unchecked public spending, Hollande says, “was not stimulus. It was submission, acceptance … It was just the easy way out.”

He believes that voters’ priorities have changed. “The French people are now saying we want lower spending,” he tells TIME, “but on condition that there is a purpose, that it creates jobs, that it improves competitiveness, that it contributes to investment.”

French Toast

“Let the crisis attain its paroxysm to be able then, only then, to resolve it,” said Mitterrand as he attempted to pilot far-reaching reforms of the French school system in the 1980s. He calculated that his compatriots could be persuaded to embrace reform only by staring into the abyss. Hollande has refashioned that principle into an Obama-like narrative of hope and change, inspired in part by his memories of travel to New York City–“a huge, fascinating city, dirty and violent”–in 1974. The speed with which New York City transformed provides an example that Hollande aspires to emulate. He speaks of resilience, “where you suffer and then you become stronger … A great nation can go through setbacks, but what makes it a great nation is that it can become a leader again very quickly. And it’s the timescale that we have to shrink,” he says, breaking into English to emphasize the point: “Plus que ‘Yes we can,’ ce devrait être ‘Yes we can faster.'”

Few would doubt that a speedy upturn in France’s fortunes is vital. Hollande acknowledges that “the hope cannot be based on pure sand, on illusions just to lull the children to sleep. We have to show our capacity to carry out the reforms.” Yet a mix of circumstance and history weigh against full-throttle change.

The year ahead is dotted with elections: for municipalities, the European Parliament and the French upper house, the Senate. Deep cuts and broad reforms risk sending voters into the arms of other parties–including the far-right National Front, which, like other Euroskeptic, anti-immigration movements, has gained from turbulence in the euro zone.

But the roots of France’s crisis run deeper than the woes of the single currency. The public sector remains outsize compared with its mission. The Banque de France, the country’s central bank, lost much of its reason for being with the founding of the European Central Bank in 1998, but with 13,000 employees it remains the largest in the euro zone. Meanwhile, jobs growth in the private sector is sluggish. French companies are powerhouses abroad, but at home they have the lowest margins in Europe. “With lower margins, you invest less, hire less, do less marketing and basically are at a huge disadvantage,” says Adrien Schmidt, CEO of Squid Solutions, a Big Data startup in Paris, and president of Silicon Sentier, an association for startups.

If taxes and labor laws make it expensive for employers to create jobs, it’s sometimes even more costly to shed them. Take the U.S. tire manufacturer Goodyear, which had planned to close its factory in Amiens, 90 miles (145 km) north of Paris. Staff unhappy with the way the closure was handled took the company to court in Ohio, and on Jan. 6, union activists kidnapped two of their bosses in Amiens for two days. Two weeks later, unions and management settled on severance packages that reportedly offered between $163,000 and $176,000 per laid-off employee.

French workers expect benefits that are far more generous than those in the U.S. and most other European countries. But such largesse can’t be funded through meager French GDP growth, estimated at 0.4% in the last quarter of 2013. The cost comes in higher rates of joblessness, especially among the young, and bills that can be paid only by raising taxes or borrowing. The result is a rising debt-to-GDP ratio. But unlike peripheral euro-zone countries that have seen their borrowing costs soar, France has seen yields on its benchmark 10-year government bonds drop to 2.22%. One explanation is that the markets believe affluent Germany will never allow its neighbor and fellow champion of the European project to flounder. This has reduced the pressure on France to change. Hollande gives a more buoyant assessment. Moody’s Investors Service has reconfirmed that France’s credit rating is set to remain stable at Aa1, two years after the country lost its membership in the AAA club. The President interprets this as good news: the rating hasn’t slipped further. The glass is half full, not half empty.

A Fighter, Not a Lover

Hollande is a bona fide optimist, and his can-do spirit drives his foreign policy. Last September, Hollande arrived in Mali to see a democratic President sworn in after French troops had crushed Islamist rebel forces and was garlanded as a savior. He characterizes the military action he ordered to contain the spread of Islamist rule and stop the capital city of Bamako from falling to jihadists as “the most successful [intervention] … in the history of military operations over the last 20 years.” He knew strikes in Mali would be difficult without the backing of Algeria, the region’s military superpower, but unresolved antagonisms between France and its former colony mitigated against such an agreement. In December 2012, Hollande traveled to Algiers, made a heartfelt address to the Parliament acknowledging the atrocities of the Algerian war and won over the notoriously dour President Abdelaziz Bouteflika. “Hollande is a mixture of strong resolve and smiley, lighthearted attitude, which usually makes people feel at ease,” says Jean-Pierre Filiu, a former diplomat who accompanied Hollande to Algeria. “After two minutes with Hollande, even Bouteflika was smiling and laughing.”

French boots have been on the ground in the Central African Republic since December, in a U.N.-backed operation to try to halt a bloody civil conflict, and French troops are still in Mali and Chad. Hollande had also scrambled his forces into readiness for strikes on Syria in tandem with the U.S. when a Russian-brokered deal on chemical weapons led to an 11th-hour change of plan.

For a President seeking to reduce spending, Hollande has been quick to commit to expensive and open-ended operations. “I could, of course, have limited my actions to purely domestic issues,” he acknowledges. But he adds, “Even during this very difficult period, I wanted to demonstrate that France could assume its full responsibility on a global scale, no matter the area: human, financial, political … My message is, France is right there.”

Geopolitically speaking, that’s true. France has the largest Arab population of any West European country because of a colonial history that bequeathed it deep and complex ties with Syria and the Maghreb. When others broke off diplomatic relations with Iran, the French kept channels open. One constant feature of French foreign policy is its exceptionalism. France rarely falls into line, as successive U.S. Administrations have discovered. Hollande, who hasn’t yet locked horns with the U.S., characterized the relationship thus: “France is a solid ally of the United States but always retains its independence.”

President Jacques Chirac, in refusing to join the Iraq War, created anger and consternation in Washington. His decision means Hollande travels to the U.S. unburdened by the popular backlash against interventionism that has constrained other leaders. Following revelations that the NSA targeted French citizens, he also expects to arrive with leverage “to build a new cooperation in the field of intelligence.”

Cherchez la Femme

Hollande’s advisers will doubtless be irritated by continuing press interest in the absence of a female companion to balance out his photo call with the Obamas. Inside the Élysée Palace, there’s little sympathy for the view that Hollande’s private life is of public interest.

But the attention might not be a bad thing. Since his love life hit the headlines, Hollande’s rock-bottom ratings have edged up, if only slightly. That may partly reflect approval for his proposed responsibility pact, but the alleged affair has also made him “appear more human and closer to the people,” Axelle Lemaire, a Socialist French lawmaker, suggested to the London Evening Standard. Images of a helmeted Hollande on a scooter puttering the two blocks from the Élysée to supposed trysts are a far cry from the posturing of his predecessors. He appears approachable, faintly ridiculous, not a republican king handing down orders from his palace but an ordinary citizen, something that may make his message of mutual sacrifice more palatable to his compatriots.

And if his opponents underestimate his resolve in the face of ridicule, so much the better. They have already done so to their cost. After months of violent street protests, Hollande last May pushed through a law legalizing gay marriage and granting adoption rights to gay couples. History, though, remains stacked against anyone who tries to haul France in any one direction too quickly. Mitterrand never got his school reform through. Sarko threw in the towel on his ambitions to inject a more entrepreneurial spirit into the country that gave the world that word. Hollande–an unexpected President, unlikely reformer and unanticipated focus of tabloid fascination–needs to have a few more surprises up his sleeve.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com