In the end, it wasn’t the cyber Armageddon that it seemed to be at first glance.

What has been described as the largest ever ransomware attack–a cybercriminal scheme that locks up computer files until victims pay a ransom–holds the paradoxical distinction of being both an outrageous success (in terms of its blast radius) as well as an abject failure (in terms of its haul). The malicious software spread so far and wide, jammed up so many IT networks and generated so much panic and mayhem that the wrongdoers effectively undid themselves. Consider the burglary bungled.

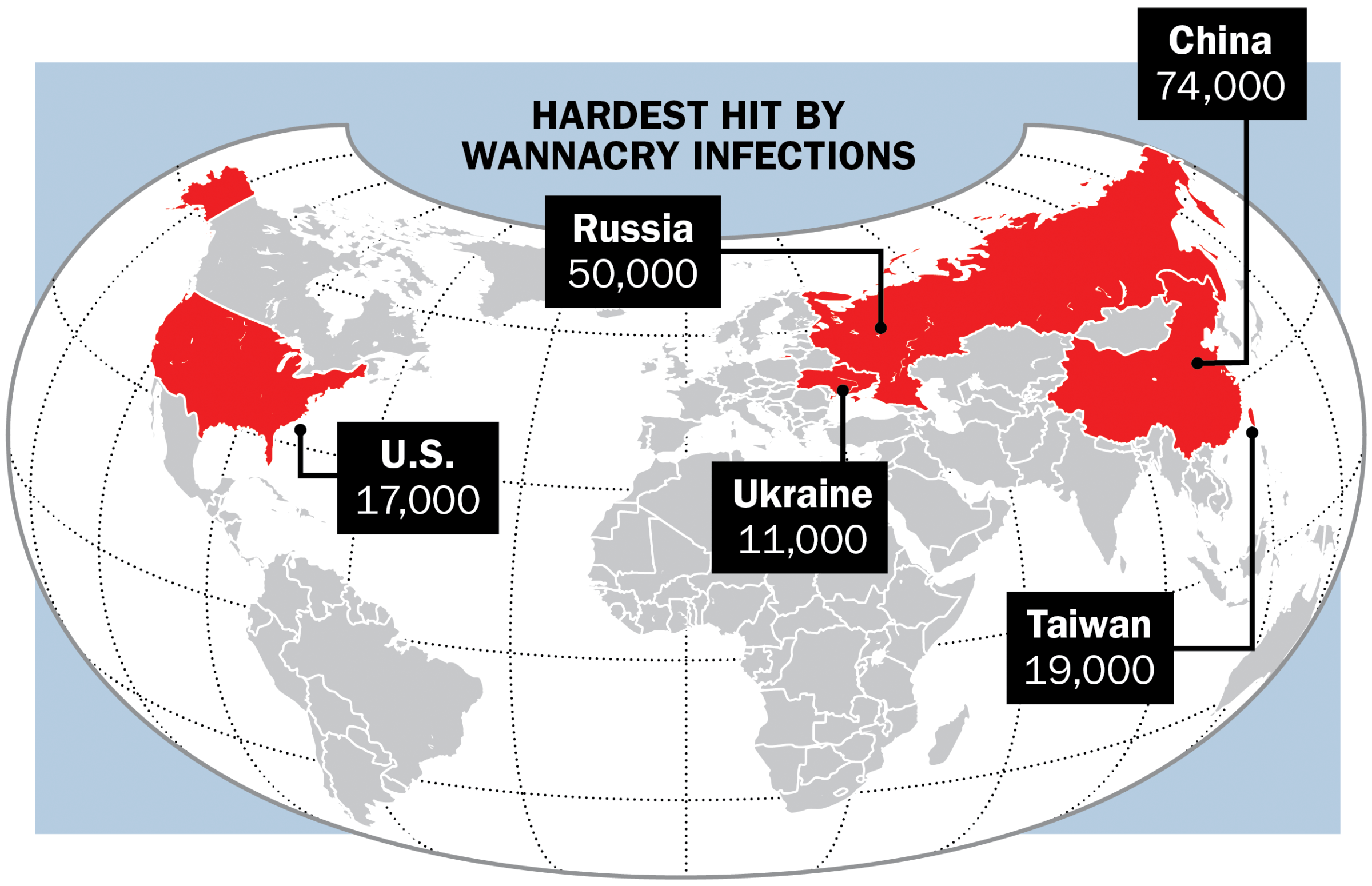

On May 12, the world awoke to the beginnings of hundreds of thousands of old Microsoft Windows-based computers’ seizing up as they succumbed to a virulent strain of malicious software, appropriately dubbed WannaCry. Within hours, the digital pandemic circled the globe like the Spanish flu, infecting machines running outdated operating systems in some 150 countries, spreading across numerous homes and corporate networks. The attack, which relied on powerful tools believed to have been developed by the NSA and leaked online in April by a group of hackers known as the Shadow Brokers, wormed its way through businesses, hospitals and governments, all of which found themselves suddenly locked out of their own systems.

Researchers detected the wave quickly, and it wasn’t long before they picked up on the criminals’ self-defeating mistakes. The attackers failed to assign each victim a separate Bitcoin wallet, researchers noted, a critical error that meant they would not be able to easily track ransom payments. They neglected to automate the money collection in a way that would scale. And then there was the matter of the kill switch.

No one is quite certain why the attackers coded a self-destruct button into their software, yet that’s precisely what they did. Marcus Hutchins, a 22-year-old security researcher based in England who goes by the moniker MalwareTech, stumbled on the power plug largely by accident. After taking lunch on that Friday afternoon, he inspected the malware and noticed a specific web address encoded within. Curious, he registered the domain for less than $11. This simple act sinkholed the malware, killing the virus’ ability to propagate and buying time for organizations to upgrade their software and deploy protections.

The attackers “had a Ferrari engine from the NSA, basically, and they put it in a Ford Focus’ body, which they got from some ransomware kit,” says Ryan Kalember, a cybersecurity strategist at Proofpoint. Despite the campaign’s prevalence, in total it has netted a measly $80,000. Compare that with the estimated $60 million annually raked in by the Angler ransomware campaign in years past.

Still, the attack caused serious damage and downtime for those affected. In response, Brad Smith, Microsoft’s president and chief legal officer, said the company shouldered “first responsibility.” Microsoft took the unusual step of providing an update for unsupported operating systems, like Windows XP, even though it had retired them years ago. Smith then took a swat at the government, criticizing its supposed habit of “stockpiling” vulnerabilities in tech companies’ code for surveillance purposes. He compared recent leaks of this information to the military’s “having some of its Tomahawk missiles stolen.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin piled on, noting that Microsoft identified the NSA as the source of the hacking tools. He added, “Russia has absolutely nothing to do with this.”

Researchers are now chasing down possible leads to find out who was behind the attack. One theory points to North Korea, though the evidence for this was tenuous at press time.

A few days after WannaCry came to light, the Shadow Brokers posted a message online stating that the group would begin a monthly data-dump service, selling access to top-notch exploits to those willing to pay. “More details in June,” the group said in a blog post. The promise presages doom to come.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com